The Enigmatic President

By Aaron Mella

David Greenberg

David Greenberg is an associate professor of History and of Journalism & Media Studies at Rutgers University, New Brunswick. He has a Bachelor of Arts from Yale University and a PhD from Columbia University. Nixon’s Shadow was Greenberg’s first book. Today, Greenberg specializes in the political and cultural history of America.

“Not any mask would have worked so well; the Nixon mask is powerful because it’s redundant – the mask of a man who seemed to be wearing a mask already.”1 The American public, disillusioned by government authority, withstood six years of chicanery during the era of media publication and television. Richard Milhous Nixon, the 37th president of the United States, hid under his mask of deceit and inauthentic appeal in a nation that longed for closure and assurance. David Greenberg’s Nixon’s Shadow: The History of an Image uncovers the numerous points of view on Nixon and his term as president. His conquest for power, authority, and leadership became his double-edged sword: loyalists complemented his resolve, while Democrats called out unrestrained tyranny. What began as a fresh beginning for American politics, turned out to be an inevitable crash for government order and trust.

The first two chapters introduce Nixon’s first exposure into politics – as a Republican primary for the California congressional district - and his ambivalent public image of deception. After a 1945 Republican defeat to Democrat Jerry Voorhis, the Republican Party looked towards a fresh, aspiring, up-and-coming politician in Richard M. Nixon. Nixon used many rhetorical strategies in order to guarantee a victory in the sphere of politics. To gain public approval, Nixon used “populist imagery to extend conservatism’s appeal beyond its upper-class base and to reach success by reviving, in his person and persona, the dream of a self-made man.”2 Combined with his universal appeal, Nixon’s notorious act of “Red-Baiting” originated during his run against Voorhis in 1946. Through a series of debates, Nixon associated Voorhis with involvement in CIO-PAC, a controversial labor union often cited with communist motives. Even though he was truly endorsed under NCPAC, the National Citizens Political Action Committee, public suspicion and discontent had already clouded Voorhis’ campaign. This determination for power and authority quickly carried over to Nixon’s future political career, evident in the 1950 Alger Hiss case, and the Helen Douglas “Pink Lady” case. Nixon’s liberal demonology, “Tricky Dick,” represented his villainous depiction of deceit in politics. Created by liberals, they criticized Nixon from his conservative party background, to his articulation in speech, and his physical appearance. Liberal politicians such as former president Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Dean Acheson ridiculed Nixon so much that the term “Nixon-hating” emerged. Through the 1950 liberals’ perspective, Nixon was corrupt, inauthentic condescending, deceptive, and unrefined: “The patriotic anti-communism admired by conservatives struck liberals as cynical Red-baiting. The everyman stylings were seen as phony populism. Nixon was… but an opportunist who exploited the new tools of television, advertising, and public relations to project a false image.”3 To ensure a republican victory in the upcoming 1952 election, Nixon was nominated vice president of popular war-hero Dwight D. Eisenhower. During a time of resentment against communism, a duo of war-hero and cold warrior stood inevitably victorious. However, several scandals tainted Nixon’s approval rating – McCarthyism, and the “Secret Funds”. The “Secret Funds” case, where Nixon supporters and loyalists donated to support his political expenses, angered liberals and accused Nixon of corruption. With the inaccuracies by overzealous senator Joe McCarthy against communists in the United States, Nixon was automatically associated as a power-hungry politician. To gain public appeal and approval, Nixon constantly shifted and revised his public relations image, evident in his 1952 Checkers Speech. A televised half hour address to the public, the Checkers Speech was Nixon’s response to the growing controversy and doubt concerning the Secret Funds. Nixon epitomized his image to the American public, reminiscing the difficult challenges his family, both past and present, had faced. An example of image crafting, Nixon convincingly won the hearts of the American public as well as a spot on the president’s ballot in 1952.

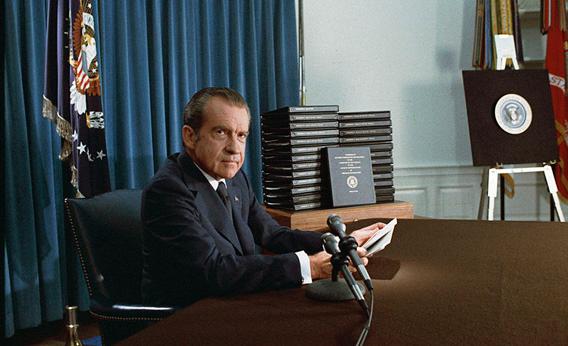

The next two chapters address Nixon’s domestic adversaries - the New Left and the media - as well as his rapacity for political dominance. The New Left, consisting of young radical students, started initially as a grassroots organization advocating for a reform in American politics. In order to achieve this proposed change in government, New Leftists targeted repression, deception, and paranoia. They claimed that Nixon was a “shadowy conspirator, a repressive dictator… who thought nothing of slaughtering civilians in the Vietnam War for his own advantage.”4 Democratic groups such as the Students for a Democratic Society, Mobe, and the Counter-Inaugural served as Nixon’s true political adversary, holding protests during speeches while shouting expletives and chanting disapproval. This nascent of tensions between the Left and Nixon characterized the 1968 presidential campaign, as well as Nixon’s future endeavors in politics: “Nixon and the left each inflated the other’s hostility into a full-blown conspiracy; each validated the other’s fears by coordinating assaults in what each believed was a last ditch to save democracy.”5 Nixon’s paranoia with Leftists led to the hiring of Henry Kissinger as the national security adviser. Kissinger would assist Nixon with wiretaps, surveillance cameras, and other means of criminality to attain the upper hand against the Left. As Nixon rose to prominence from a government representative, to Senator, to Vice President, and finally President in the 1968 election, the American public eagerly awaited the leadership of their newly elect. The media left a lasting impact on Nixon’s political career. Literature, film, music, and left-wing press echoed a concern for the authority of Nixon as America’s president: “In their eyes, Nixon became another Lyndon Johnson, stubborn and callous.”6 In addition to the anti-Nixon protests, Nixon’s first years as president were marred by the war polarization of the 1970s. After promising a “peace with honor” approach to Vietnam, the United States contradicted its policy with an invasion of Cambodia. Unnecessary foreign entanglements led to riots and shootings at Kent State University on May 4th, 1970. This public distress stirred up controversy, as well as an excuse for Leftists to retaliate against Nixon. Again, with the public concern looming over him, Nixon responded with an attempt to shape-shift his image – the October 29th, 1970 San Jose anti-war protests. Following a campaign speech in a San Jose school, Nixon departed with stones thrown by anti-war protesters. However, “Nixon wanted them there because he knew that, in the eyes of most Americans, the radicals made him look good.”7 The incident was used to make Nixon seem innocent, assaulted, and endangered against the Left. This clever PR move foreshadowed the coming of the Watergate scandal in 1972, as Nixon attempted to conceal his true deceptiveness under his ever-shifting mask of innocence, dishonesty, and greed. To uncover the truth about the enigmatic president, the Washington Press Corps introduced a new style of journalism, described a return to muckraking: “Reporters saw themselves as embattled truth-seekers fighting the president’s vast public relations machine.”8 Nixon combated with the increased presence of the press, claiming himself as a “New Nixon,” a shift from the power hungry “Tricky Dick” to a more mature and tolerant government leader. Two liberals who raised concern over Nixon’s image making were Daniel Boorstin and Joe McGinniss. With their book, The Selling of the President, they called out the president’s PR and media tactics, while encouraging more analytical, accurate, and unbiased press reports. After receiving ridicule from CBS for Nixon’s “Silent Majority” speech, Spiro Agnew, the vice president, furiously responded. He gave his own speech, criticizing the media as “biased, sensationalist, and irresponsible.” Shortly after, Agnew again delivered another speech, this time criticizing the Washington Post and the New York Times. Agnew’s retaliation epitomized Nixon’s detachment from the press as a result of ongoing banter and conflict. His anti-press and anti-media movement clouded his tenure as president in 1968 and 1972. The Nixon-press feud did not stop there. In 1971, Daniel Ellsberg released the Pentagon Papers, a report that uncovered classified accounts regarding the Vietnam War. After failing to repeal the article on the New York Times about the documents, Nixon hired the plumbers – an unofficial cabinet for the president. The plumbers, through Nixon’s leadership, attempted to break into Ellsberg’s psychoanalyst, seeking any evidence to blackmail Ellsberg from denying the Pentagon Papers. The controversy surrounding the Nixon presidency continued with the 1972 Watergate scandal. Initially, the president was kept clean from any accusations of the break in because of the press’s fixed attention on the 1972 presidential campaign. Two members of the Washington Post, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, decided to uncover the truth about the Watergate scandal. In their book, All the President’s Men, Woodward and Bernstein diverted the public attention back to the president, and suspicions aroused. During the Watergate scandal popularity, reporters reverted back to the sensationalist criticism of Nixon, as well as uncovering other scandals such as his use of federal funds for property, and the personal reduction of taxes. After Nixon’s dishonesty led to his demise in the Watergate scandal, “many concluded [Nixon] was something much worse than a wily news manager; he was a liar… whose need to control the news overrode ethical compunctions and even legal limits.”9 Nixon’s greed for authority led to his prominence and fall as a government official.

Chapters 5 and 6 cover the Nixon administration’s fall from grace because of the 1972 Watergate scandal. The Watergate scandal was not the end-all-be-all for the Nixon administration. Nixon loyalists still strongly held to the belief that he was the victim of another witch-hunt by the press. Loyalist groups such as the Committee of Fairness, led by Baruch Korff, started as a grassroots organization, and quickly gained national popularity. They created another “New Nixon” image; Nixon was a victim of false conspiracy. His supporters ridiculed the press’s persecution, while perceived him as innocent. Nixon’s motives for seeking information from the 1972 Democratic Convention were based on his past defeat in the 1960 election. Nixon held a grudge with John F. Kennedy ever since 1960, where he lost because of his poor appearance as a leader. The Democrats immediately jumped on the Nixon-hating bandwagon after the Watergate scandal, hoping to find an advantage in politics: “The Democrats, the victims of the burglary, were said to be engaging in ‘character assassination,’ while Nixon and his men, the culprits, were painted as innocents.”10 Despite the Watergate break in, Democrats did not benefit from the persecution of Nixon. The witch-hunts depicted the Democratic candidate George McGovern’s desperation for approval. After the Senate trials for the Watergate scandal, Spiro Agnew resigned in 1973. Nixon lost the middle and moderate support that he strived to attain ever since his introduction to politics in 1947. He continuously argued that Kennedy and Johnson used similar taps during their presidencies. Attempting to reconstruct what was left of his PR image, Nixon also criticized Ellsberg’s Pentagon Papers, and associated them to his Watergate scandal. Nixon championed the “everybody does it” argument, but to no avail. After Watergate and the 1974 resignation, psychobiographers looked back to their studies of Nixon as president.

Chapters 7 and 8 depict Nixon’s legacy after his 1974 resignation. Although dissimilar in length to the past chapters, Greenberg conveys that “Nixon’s variety ‘contained more of the essence of populism than of the pristine ideological right.”11 As Nixon departed from office in 1974, his legacy as a manipulative and spurious president is still prone to mockery and criticism today.

David Greenberg’s book strives to convey that Richard Nixon’s political career cannot be analyzed solely through a historical lens. With the features of mass media, public perception and relation greatly affect one’s potential to succeed or fail, whether in politics, profession, or relationships. The motivation for a belief represents the strength and weakness of man – anything that can increase vitality and success can easily take it away. Greenberg asserts this case in his study of the different points of view on Nixon. He writes, “Nixon remained a symbol of thrusting ambition gone amok, of a powerlust and concern for image and reputation so deep and unquenchable that neither death nor dishonor could deter their eruption.”12 Nixon’s success in politics ultimately led to his ethical downfall as a president, politician, and person.

David Greenberg began his journalism career as Acting Editor and Managing Editor of The New Republic magazine. Early in his career, he served as assistant to author Bob Woodward, author of All the President’s Men.13 His past profession as an editor for the liberal magazine, The New Republic, might contribute to his purpose in writing a book about Richard Nixon. As a liberal magazine, known for its criticisms on republicans and conservatives, The New Republic may have inspired Greenberg for his work. Also, his experience in journalism and history factors in his decision for holding a qualified point of view on Nixon. Greenberg wrote Nixon’s Shadow: The History of an Image in 2003. This time period followed the traumatizing event of 9/11, and the Bush administration’s declaration of a War on Terror in Iraq. During this time of national security, Greenberg could have been motivated to revisit America’s history of controversy and discontent with government during the mid-1900s.

According to the Karl Helicher’s book review, “this investigation demonstrates how Nixon’s sympathizers – conservatives, loyalists, and members of the foreign policy establishment – and his detractors – psychobiographers, the New Left, and liberals – responded to his political shape shifting.”14 Helicher’s review, although short and concise, holds positive reviews for Greenberg’s book. The review praises Greenberg for his study on the different perspectives of Nixon, as well as the inclusion for media and press accounts on Nixon. Likewise, journalist Mark Feldstein’s book review praises Greenberg’s work on Nixon. Feldstein writes, “Nixon’s Shadow is beautifully written, graceful and even elegant in style, sophisticated and nuanced in content. It is accessible to the lay reader as well as the scholar without sacrificing intellectual complexity or depth.”15 Feldstein commends the unique perspectives that Greenberg structures his work around. He states that the study on Nixon’s image shifting was key in distinguishing other books regarding Nixon’s controversial presidential career.

David Greenberg’s Nixon’s Shadow: The History of an Image was an insightful look into the mind of Richard Nixon. Greenberg’s unique structure of the differing interpretations of Nixon as a politician, leader, and adversary immediately seizes the reader’s attention. Greenberg’s thesis – the mental aspect of Nixon was just as important as his career as politician – encourages appraisement and discussion. Although somewhat biased for the liberal point of view, Greenberg successfully correlates the nascent and demise of Nixon to the effects of the press, media, and opposing parties. He writes, “America developed a culture in which the acknowledgment of the role of constructed images… came to underpin discussions of public events.”16 This unique viewpoint on Nixon’s presidential term distinguished Greenberg’s work as more than a biography of Nixon, but a case study into the trepidation of 1970’s politics. Greenberg, through his work, notes that the 1970s was a time of controversy, distrust, and deception. The 1970s were not only a continuation of the 60s, but an increase in public discontent and national polarization. With the homestretch years of the Vietnam War looming, Americans desperately yearned for a cease in conflict, both domestic and foreign. After the resignation of President Nixon in 1974, and the fall of Saigon in 1975, America’s morale reached it’s all time nadir. Greenberg writes, “The elusiveness of Nixon’s true self has made him a rich symbol… Nixon’s longevity and prominence in postwar American life render that elusiveness all the more striking.”17 The 1970s not only shifted America’s view on politics, but rendered politicians vulnerable to public ridicule and backlash. Political distrust began in the mid 1900s, peaked in the 1970s, and continues today, nationally and worldwide.

David Greenberg’s Nixon’s Shadow: The History of an Image, dives into the political and controversial mind of Richard M. Nixon during the mid and late 1900s. His career as America’s illustrious hero to the nation’s most despised villain fully embodies the incumbency of the Nixon administration. Through his presidency, Nixon fully altered the meaning of “politician”, changing America’s perception of politics forever. Greenberg’s work delivers a powerful study of Nixon’s rise and fall from grace in America.

Footnotes:

- Greenberg, David. Nixon’s Shadow: The History of an Image. New York: W.W. Nortan & Company, 2003. XVI.

- Greenberg, David. 5.

- Greenberg, David. 39.

- Greenberg, David. 76.

- Greenberg, David. 79.

- Greenberg, David. 88.

- Greenberg, David. 96.

- Greenberg, David. 131.

- Greenberg, David. 143.

- Greenberg, David. 190.

- Greenberg, David. 330.

- Greenberg, David. 345.

- David Greenberg. Rutgers University, n.d. Web. 01 June 2015. <http://comminfo.rutgers.edu/~davidgr/>.

- Helicher, Karl. “Nixon’s Shadow: The History of an Image (Book).” Rev. of NIXON’S Shadow (Book). Library Journal 128.13 (2003): 100. Print.

- Feldstein, Mark. “Nixon’s Shadow: The History of an Image (Book).” Rev. of NIXON’S Shadow (Book). Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 81.1 (2004): 207-09. Print.

- Greenberg, David. XXII.

- Greenberg, David. 347.

1 - 4

<

>