The Truth About Vietnam

By Alex Yamamura

Adam Garfinkle

Adam Garfinkle is an editor for the American Interest, a public policy magazine. He teaches at the university level and is a staff member of the U.S.government. Previously a speechwriter for George W. Bush’s Secretaries of State, he holds a B.A. , M.A. , and a PhD in International Relations from the University of Pennsylvania.

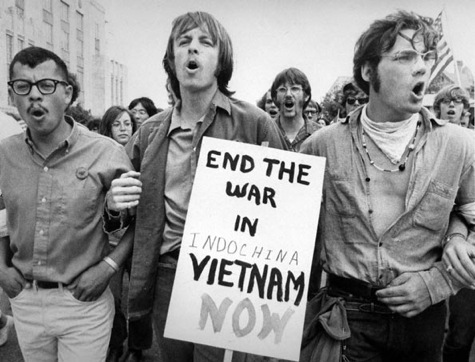

Although war continues to be considered a necessary evil, there are many who adamantly oppose war as a means of solving international disputes. One of the most complex examples of the ever-present antiwar movement is Vietnam. While we may have lost the war, Adam Garfinkle in his book, Telltale Heart: The Origins and Impact of the Vietnam Antiwar Movement, believed that the antiwar movement hindered rather than helped the U.S. in the war, and prevented a possibly “winnable” war.

In the book, Garfinkle emphasizes the futility of the antiwar movement during the Vietnamese War. He begins by claiming that there was no real correlation to the antiwar effort and its effects on public and government action. He attempts to dispel the radical myths surrounding the movement concocted by the belligerent war hawks and the peace-seeking doves; First the war hawk’s version that the “war was winnable, but that the press, micromanaging civilian game theorists in the Pentagon, and the antiwar hippies lost it” versus the doves’ version that “the war was unwise and unwinnable no matter how much firepower was used. The United States was on the war side, fighting a righteous peasant uprising against a tyranny.”1 In both cases, it was mutually agreed that poor leadership resulted in the lost Vietnam War. Another misconception Garfinkle addresses is the belief that the antiwar movement was led by students and communists. Also, counter-productivity may have encouraged Hanoi to press on in the war believing they had an unintentional ally due to internal opposition. Finally, the antiwar influence on governmental actions during President Johnson’s time during the weeks after the Tet offensive served as a psychological influence that altered the radial policy towards war and slowed support to the war effort. Ultimately the antiwar efforts appeared unsuccessful in preventing war in Vietnam, as while there may have been high antiwar sentiments, this was not equal to antiwar activism. Party loyalty, patriotism, sensitivity to war costs, and shifts in administrative policy all factored into the state of antiwar opinions too. There was a variety of protestors that weakened the antiwar movement as well. For many different reasons, pacifists, Christians, New Leftists, Leftists, Radical rights, students and women all opposed war. While such diversity meant that the war was unpopular among many groups, it also prevented any unified antiwar movement with overwhelming strength in numbers. With civil rights taking a backseat in the war, and mixed opinions over immediate withdrawal or negotiation in Vietnam, the antiwar movement was definitively divided and barely noticed at all.

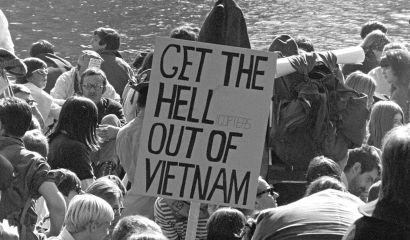

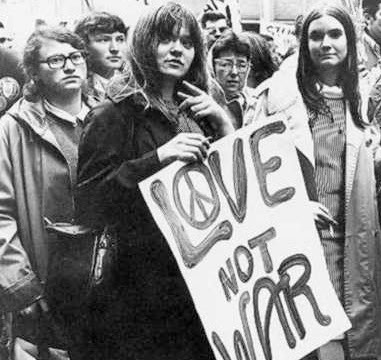

When President Kennedy took the presidency, the nation began facing its problems and moving to solve them. “The nation discovered physical fitness, the first lady was stunning, the kids were cute, and the President managed to inspire admiring, respectful comedy. When he was murdered, it was as if the new spirit of the nation dissolved…With Kennedy’s murder also came the end of American restraint in Vietnam.”2 As more people became antagonistic towards the war, rallies grew and protests became more numerous. Still, the main groups supporting peaceful reactions in Vietnam held intense distaste towards each other. The Liberals centered around the National committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE), the Radical Left/ New Left with the Students for Democratic Society (SDS), and the New Pacifists composed of the War Resisters League, Committee for Non-Violent Action, and Fellowship of Reconciliation, continued to have different plans that often led to increasing demands. While the author claims that the antiwar protests were largely unsuccessful, he does acknowledge the peak of the movement, around the massive rallies held by several different groups. The April and June rallies, expounded by SDS encouragement, resulted in an unprecedented size and press coverage of the event. Later, SANE and the Left-Liberals held their own rally demanding an immediate ceasefire followed by negotiation rather than withdrawal. Draft opposition also was key to understanding the differences between liberals and radicals. More radicals began integrating the draft as a touchstone issue. Music changed during this time too, with a striking adjustment to serious lyrics and politicization of youth music. The biggest support for the antiwar movement came about during the Johnson administration. The government’s problem came “in July, (when) the Joint Economic committee determined that the war, in 1967, would cost between $4 and $6 billion more than the $20.3 billion the administration had requested- this, it will be recalled, just a few years after Robert McNamara had told the Congress that the U.S. could afford to fight a limited war in Vietnam ‘forever’.”3 Now that the cost of the war became apparent, taxpayers looked to television and radio to hear the startling body count, see rising costs, and experience increasing radical protests. The youth of Vietnam lost credibility as well however, as the rising antiwar movement was also associated with the increased drug and sex lifestyle new to this era. Several scandals with drug use, so called ‘sexual therapy’, and other inappropriate behaviors led to the loss in face for the overall antiwar movement. This ridiculous conduct culminated in a strange episode where thousands of youths tried to levitate the Pentagon, misled by the mixing of religion and politics.

There was an obvious shift from nonviolence to resistance during the Vietnam War. New left and the SDS utilized increasingly violent tactics in their protests antics. One of greatest turning points in government policy occurred after the Tet offensive. The Wise men, presidential advisors, urged President Johnson to take immediate action against the potential rising of antiwar sentiment. In the face of such opposition, the Wise men feared that divisions in the country would force the U.S. to withdraw from the war, after realizing that the war would still be unwinnable at the current pace. However, their views were probably misled by the public polls, which had in fact generated support for the war in itself. Additionally, their fear that Congress would force a withdrawal was unfounded. President Johnson had created an equal split between hawks and doves in society at 41% each; a large difference from the 61% hawk and 23% doves before. This antiwar shift also was accompanied by more violent protests and more violent responses, with arrests and the use of teargas in unruly demonstrations. Student protests escalated into gunfire at Kent State and Jackson State universities in May 1970, leading to the shutdown of college campuses. These shootings had a large influence on the war effort, as “it was only after Kent State that the May 1970 demonstrations took on their vast scale.”4 Other school protests kept their antiwar themes, but merged with problems with university policies. Once schools and Congress began instituting antiwar policy however, the antiwar movement died easily if unexpectedly. Some schools created peace symbols on campus to quell student activism, and the generation became more concerned with getting a good job than moral issues as the booming economy slowed. The activism during Nixon’s détente was also affected since Vietnam became the center of U.S. foreign policy. Since Vietnam stood between the U.S. and policy success in China and Soviet Union, Nixon concocted his ‘peace with honor’ plan. While détente eventually failed, as did Nixon’s reinvented policy of containment, the antiwar movement did enter the minds of Congress and progress these ideas into withdrawing from Vietnam.

According to Garfinkle, Vietnam could also be considered a metaphor in later years. Since Vietnam ended ambiguously, there were many different interpretations on its consequences. Certain key ideas were more clearly defined during this time, such as the need for physical survival being the preeminent goal of foreign policy. The psychological fatigue from Vietnam left society in a state of denial, stuffing Vietnam into the backs of their minds. Humility was also a factor in keeping talks about Vietnam hushed. As many books on Vietnam became published, the divided memories on Vietnam along with the unwillingness to remember the events during the war led to the “greatest problem with the existing literature on the movement is not a general ideological bias but its inability to separate analysis from both moral judgement and personal location. It fails to examine seriously fundamental questions about the war itself and, by assuming a two-dimensional understanding of the war, judgments on the antiwar movement come out flat as well.”5 Garfinkle goes on the compare Vietnam to the Kuwait crisis in 1990-1991. Kuwait was the only other war since Vietnam to produce a similar antiwar movement. The media and press also expanded the scope of the movement. Some of the lessons to be learned from Vietnam also extend to Vietnam syndrome, where a numb U.S. government and public feared that war would not be winnable without complete support. However, the question of whether victory in Kuwait ended the Vietnam syndrome has yet to be answered. Had war become more acceptable as a solution to conflict? Analysis has still not produced an answer. Still, Garfinkle believed that the major effects of the Vietnam War were still felt mainly in the U.S. rather than Southeast Asia. As those in the Vietnam generation grew up, more and more people began seeing the military and government as the enemy, rather than foreign antagonists. The fact remains that much of the adversary culture produced from the antiwar movement contained a large margin, making it necessary to see it in both the good and bad lights. Garfinkle emphasizes seeing both sides of the issue and keeping both biases and influential memories in mind when evaluating the impacts in Vietnam as well.

While the views on the antiwar movement on Vietnam vary, Garfinkle believed that the antiwar movement had little influence on the actions in Vietnam, as they did little to hinder and even less to help the overall war effort. He creates four main points to prove in his book: First that the observation that the “antiwar movement ‘played a major role in constraining, de-escalating and ending the war,’ are wrong”. Second that the war in Vietnam was the main catalyst for 1960’s radicalism, not the cause.6 Third, that the antiwar movement was like “a modern children’s crusade, with similarly depressing consequences,” and fourth, that the main impact of the war was not felt in Southeast Asia but in the United States.7 His final thesis is most strongly supported by the societal reaction in the aftermath of Vietnam, with a (perhaps misguided) belief that people had the power to change things, and as such promoted a more democratic lifestyle. Also that at a time when America seemed to fall apart, the political system adapted to the voices of America and allowed for stabilization after a humiliating defeat.

Throughout his career, Adam Garfinkle was an editor, professor, and speechwriter for many important publications and people. Most notable are his roles as a speechwriter for George W. Bush’s secretaries of state, Colin Powell and Conoleezza Rice. Part of the democratic party, he also worked in the Foreign Policy Research Institute where he had firsthand experience studying Middle Eastern politics and general American foreign policy. One of the most striking aspects of the book is its incorporation of both religion and party in the influences of Vietnam. Garfinkle, as a Jew, would be interested in the efforts of Christians and their views on the antiwar effort. He, as a democrat, would consider the perspective of his own Democratic party. Born in 1951, he also lived through the very period he is writing his book on. While this gives us a crucial eyewitness experience, it also presents a bias since Garfinkle would have been a child when the war began, and nearly in college by the time the movement hit its peak. To him, Vietnam might have seemed like an inconsequential country until after it ended, even more so when he had to look back from 1995 and see, just after the Persian Gulf war and Kuwait, how a war from his hazy childhood compared to the huge operation facing him at the time. His views are possibly summed up by his statement that “American intervention in Vietnam (that it) was a civil war. This wasn’t really true for the Vietnamese, but in an intellectual sense at least, a civil war is exactly what Vietnam became, and remains, for Americans.”8

Thomas Powers of the New York Times and Lloyd C. Gardner of the Humanities and Social Sciences Network both acknowledged the arguments that Garfinkle attempted to make in the Telltale Heart, although they disagreed with certain points Garfinkle made. Powers especially commented on Garfinkle’s failure to address prior events, and “the war’s deeper fatality- that our early support for the French in Indochina meant we were bound to fight it…No democratic people can remain indifferent when its sons are fighting a bloody war.”9 Of course, he also points out that this is merely a difference in opinions and focus, not a flaw in Garfinkle’s book. Gardner approves of Garfinkle’s efforts to dispel the myths surrounding Vietnam, concluding by quoting from the book “Only when ‘we’ accept the ironies of an anti-war movement that prolonged the war and produced such monstrosities as the eco-anarchists, he writes, ‘will we ever forgive ourselves for what we have said and done to each other these many long years.’ To which, ‘Amen’ is the only appropriate ending.”10

While the book focuses on the theses proposed by the author, there was enough evidence to support each of his claims. Of course, having four theses also creates a sense that the author is not focused on the subject, but it is a minor factor in his main objective of proving that the U.S. felt the main impact of the war. Garfinkle’s perspective was very different from what many believed the antiwar movement had accomplished. While the public view on the antiwar movement believed it righteous and helpful, Garfinkle’s argument that it had almost no influence on the war was quite convincing. He proclaimed that “such inane logic is usually safely and properly dismissed- except when the president of the United States is one of those so proclaiming, as in fact he did. Then it becomes a different sort of problem, that of historical truths being mangled publically in high places.”11 Overall, Garfinkle produced a riveting argument that denounced several myths many would not have acknowledged before.

According to Garfinkle, the 70’s were a time of intense but futile protests. The United States was facing a huge crisis when deciding on foreign policy in Vietnam, which weak leadership ultimately lost. Thanks to Nixon’s deception, many people believed in 1970 that the war was nearly over. “The body counts were getting smaller, escalation of the air war was not common knowledge, and the average American though that within a year…the fighting would be over, or virtually over…Just days later President Nixon ordered the invasion of Cambodia.”12 This announcement caused resounding student protests and hugely unpopular ratings against the government actions. It is by this time that antiwar activism became more violent, and the previous “civil disobedience” shifted into rowdy demonstration. Overall, there was a noticeable change from the 1960’s beginning with Nixon’s Cambodia announcement and the shootings at Kent and Jackson state universities. The overall effect of the antiwar movement also became more prominent in the 1970’s, as government actions began taking into account the presumed feelings of the people.

While still believing that the Vietnam antiwar movement was insignificant towards aiding the U.S. in Vietnam, Garfinkle critiqued the views on Vietnam as objectively as he could. Ironically, the one ubiquitous idea “drawn by hawks and doves, the only one held more or less in common is flat wrong. That is the widespread assumption that the antiwar movement was successful, even decisively instrumental, in limiting and ultimately stopping U.S. military activity in Southeast Asia.”13 Through close analysis and intense study, Garfinkle presents a conclusion that, while unpopular, is not one to be taken lightly.

Footnotes

- Garfinkle, Adam. Telltale Heart: The Origins and Impact of the Vietnam Antiwar Movement. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995. p. 7.

- Garfinkle, Adam. p. 57.

- Garfinkle, Adam. p. 100.

- Garfinkle, Adam. p. 187.

- Garfinkle, Adam. p. 237.

- Garfinkle, Adam. p. 3.

- Garfinkle, Adam. p. 3.

- Garfinkle, Adam. p. 299.

- Powers, Thomas. “Running Argument.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 16 Sept. 1995. Web. 31 May 2015. <http:// www.nytimes.com/1995/09/17/books/running-argument.html>.

- Gardner, Lloyd C. “No End of the Madness.” Rev. of H-Net. n.d.: n. pag. H-Net Online. H-Net, Oct. 1997. Web. 31 May 2015. <http://www.h-net.org/ reviews/showrev.php?id=1420>.

- Garfinkle, Adam p. 302.

- Garfinkle, Adam p. 187.

- Garfinkle, Adam p. 9.

1 - 4

<

>