Questioning Homosexuality

By Ashley Kim

Fred Fejas

Fred Fejas teaches Multimedia Journalism and Studies at Florida Atlantic University. He received his PhD from University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign in 1982. Some of his other works include Imperialism, Media and the Good Neighbor: New Deal Foreign Policy and United States Shortwave Broadcasting to Latin America, and The Ideology of the Information Age.

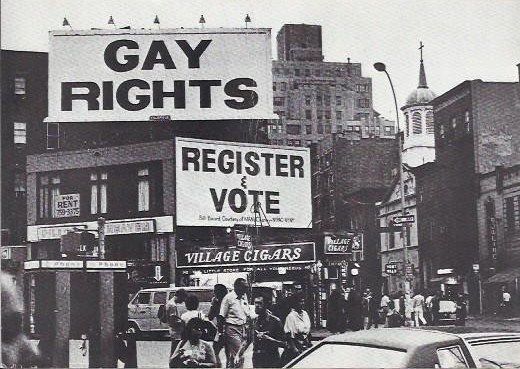

Highlighting the struggle that lesbians and gay men endured during the 1970s, Fred Fejes focuses his book Gay Rights and Moral Panic on the fight for gay rights. The homosexuals were the “focal point of anxiety,” of moral panics or as Fejes put it, “the target of intense media attention and government crackdowns.”1 Homosexuals had to deal with many discriminations throughout the nation, and the 1977 and 1978 campaigns include the fight for equal rights of homosexuals. Fejes describes the campaign and gay rights debate in various areas like Miami, California, Seattle, and also the opponents of homosexuals, like Anita Bryant.

In the 1970s, after many years of advocating for equal rights and trying to get rid of laws that discriminated homosexuals, many lesbians and gay men thought they could gain recognition as citizens and equal human beings. Commissioners of Dade County, Florida met on January 18, 1977 to vote on a law banning the discrimination of homosexuals. The commission was met with disapproval from local Catholic and Baptist church leaders, conservative political activists and Anita Bryant, “a Miami beach resident, popular entertainer…a face familiar to many Americans.”2 Her reason for opposition was that her most important role was a mother to her children. To escape discrimination, there were separate communities for lesbians and gays in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York. Homosexuals also found that colleges provided more tolerant environments where they could openly explore their sexual identity, but it was hard to adjust to the real world after college. Before the 1940s, homosexuals were known as the “fairy,” referring to male homosexuals who acted and dressed effeminately.3 Although the “fairy” raised little threat, lesbians, often portrayed as masculine, were threatening because a woman was “assuming a man’s role.”4 There were many explanations behind homosexuality, like mental disorders, poor parenting, maladjustment, or social causes like the Depression or the war. After the 1940s, homosexuals were called the “sick, threatening, abnormal, difficult-to-detect pervert, a criminal on the prowl to seduce impressionable young children into a perverted lifestyle.”5 Magazines, like Time and Newsweek, began to reflect this attitude towards homosexuals in their articles. A shift in how the media depicted homosexuals in 1957 occurred when Evelyn Hooker, using samples of homosexual and heterosexual men, proved that there was no difference in psychological health between the groups of men.6 With these changes in how media viewed homosexuals, many homosexual communities started movements. On June 27, 1969, homosexuals fought back at a police gay bar raid at Stonewall in Greenwich Village. In December 1973, the American Psychiatric Association said that homosexuality was no longer a mental illness, and the New York Times Magazine published an article that “rejected previous medical understandings of homosexuality as an illness and argued that it was a normal expression of sexuality that ‘exists to a certain degree in all people.’”7 It was too late though because the media had already created a negative view on homosexuality.

By the mid-1970s, activists started to demand legal protection for lesbians and gay men from “discrimination in housing, employment, and public accommodations.”8 Several cities passed laws protecting homosexuals from discrimination, but they were passed quietly and lacked effective enforcement. One of the main places that became important in history was Miami, which had a booming “gay night life.”9 In the summer of 1954, Miami’s mayor and the Herald “conducted an intense six-week campaign to close bars catering to homosexuals.”10 Following the changing trend of America in the 1970s, the newspapers in Miami began to shift their view on homosexuals to the minority group oppression. Fejes lists three important people in Miami’s gay community, Jack Campbell, Bob Basker, and Bob Kunst. These three key figures and several others met, calling themselves the Dade County Coalition for the Humanistic Rights of Gays, to discuss a countywide nondiscrimination ordinance. Although gay activists hoped that religious figures would help change the attitudes of Americans toward homosexuals, the Southern Baptists strongly opposed homosexuality and wanted more restrictive discrimination laws against them. Rev. William Chapman, pastor of Northwest Baptist Church — one of the largest Miami churches — turned to Anita Bryant for help, who claimed to not hate homosexuals but said it was “a violation of her civil rights as a parent to have open homosexuals teach her children.”11 The ordinance passed despite Bryant’s attempts to thwart it. Although Anita Bryant was incredibly disappointed about the passage of the ordinance, she and several others began to organize opponents of the ordinance, creating a group called Save Our Children. Their main effort would be “a petition drive for a public referendum on the ordinance.”12 Bryant had already gained the support of the media by claiming “she had become the victim of a gay-inspired blacklist that resulted in her contract for hosting a planned television being cancelled.”13 By now, Miami had garnered the attention of national media. Save Our Children gathered 11,972 signatures, and the county commission decided to hold a special repeal election on June 7.

Because no one in the coalition knew how to organize campaigns, coalition leaders turned to Ethan Geto and Jim Foster for help. Geto focused on campaign organization, commissioning a professional poll, and gaining ordinance supports. Bryant was also campaigning by appearing on national television and running advertisements in the Sunday Miami Herald. Save Our Children’s main focus was to get noticed by the public consistently. Although Bryant succeeded in gaining publicity, she failed to eloquently present herself in debates against Shack and Kunst. A strategy of both was to appeal to key voting blocks in Dade County. Voting day arrived on June 7, and an overwhelming amount of voters rejected the ordinance. Coalition leaders achieved exposure of gay rights to the general public; however, the turnout of the election crushed many hopes of lesbians and gay men. Anita Bryant had now officially become a huge threat to lesbians and gays. Although Bryant gained a lot of media attention throughout the Miami campaign, it began to backfire. For example, the Florida Citrus Commission “announced that Bryant’s contract with the commission might not be renewed, citing Bryant’s negative publicity of her campaign against the ordinance.”14 Not only was her major source of income jeopardized, but many of her tickets for her concerts were no longer being sold also. St. Paul, Wichita, and Eugene were also starting their repeal campaigns of the ordinances. For lesbians and gay men, these campaigns were their way of overcoming the defeat in Miami. However, hopes were crushed when voters in St. Paul, Wichita, and Eugene repealed the ordinance.

John V. Briggs set the stage for gay rights in California. Conservative Briggs wanted to use homosexuality to bring America back to its traditional values. On August 3, he “announced a statewide petition drive for a ballot initiative barring public school teachers who engaged in either homosexual activity or homosexual conduct.”15 Similarly in Seattle, David Estes proposed to “allow any employer or landlord to simply accuse someone of homosexuality in order to fire or refuse rent to them.”16 Seattle’s lesbian and gay community responded by creating Citizens to Retain Fair Employment, saying that homosexuals were a part of Seattle’s community and could not be discriminated against. Both Briggs and Estes succeeded in bringing their petitions to the November ballot. Kunst, in Miami, began to gather signatures for his Sunshine Party’s petition “for a country referendum seeking to bar discrimination on the basis of ‘affectional and sexual preferences.’”17 On November 7, voters went to the polls. Proposition Six, Initiative Thirteen, and the ordinance all failed to pass. Although Anita Bryant was ecstatic at her victory in Miami, she revealed on May 23, 1980 that she was suing her husband for divorce. She said “had used drugs and alcohol to cope with her problems.”18 This severely damaged what was left of her career and reputation, and people used her divorce as a proof of her hypocrisy. Fejes emphasizes at the end of his book that homosexuals had not fully gained their rights. It was not until 2003 that “the Supreme Court in Lawrence vs. Texas truly gave the privacy rights of lesbians and gay men constitutional protection.”19

Fejes believed that homosexuals had been and are still being wrongly treated with “no political or moral leader of national stature stepp[ing] forward to condemn the oppression of lesbians and gay men and to openly welcome them as part of American life.”20 He describes throughout his entire book the terrible treatment gay people were forced to endure, like being called “sick” or “immoral.” Also, 1940s and 1950s media had already ruined the image of homosexuals with articles on how homosexuality was “an increasingly dangerous phenomenon.”21 By the time people tried to speak on homosexuals and how they were not “sick monsters,” the general public had already made up their mind about gay people. Fejes says, “Gay people had rights — rights as de-sexed citizens” at the end of the book to once again highlight that homosexuals were and still aren’t accepted wholly by society as homosexuals.22 Fejes centralized his book around the idea of the mistreatment of homosexuals, providing the details of the discrimination homosexuals faced in society.

Fred Fejes specializes in Media Studies and Multimedia Journalism. Some of his other works include Imperialism, Media and the Good Neighbor, and Ideology of the Information Age. He received a Roy F. Aarons Award for contribution to the research of the LGBT community. He is currently director of the project “Generations: an Oral History of the South Florida Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Community.” Him teaching multimedia journalism and studies explains his reason for incorporating the chapter “The Strange Media Career of the Homosexual.” He writes, “a full understanding of the campaigns of 1977 and 1978 is only possible with an awareness of these media accounts and images and the meanings and anxieties they called up” and proceeds to explain how media influenced homosexuality in America.23 Fejes thought that media played the most important role in the development of attitudes towards homosexuals. The chapter about media is the most detailed and thorough, considering it is his area of expertise.

Gay Rights and Moral Panic was written in 2008, many years after the campaigns of 1977 and 1978. In 2000, Vermont was the first state to legally recognize civil unions between gay or lesbian couples. By 2008, some states began legally recognizing civil unions. Even in 2008, homosexuals still did not have the same rights as heterosexuals. Although faced with less opposition than the 1970s, homosexuals today still struggle with acceptance in American society. Fejes ends the book with “just how — and where — [are] the rights [that] homosexuals share with others” and says “it is a question that America has yet to answer.”24 Like Fejes wrote, lesbians and gay men have gained more exposure and nationwide interest, but they have not yet confirmed their rights. Gay Rights and Moral Panic shows the struggles that homosexuals had to endure for several decades and even now.

Peter Cava praised Fred Fejes in his review of Gay Rights and Moral Panic in that the “overall portrait Fejes weaves is thorough, copiously documented, compelling, and valuable for all who wish to deepen their knowledge of US gay history without accessing multitudinous primary sources.”25 However, Cava also mentions that the book did lack more information on US media and medical and legislative attitudes toward homosexuality in the early 1900s and also that Fejes also did not answer the question about gay rights. Cava is also concerned about how Fejes asserts in his book that the Stonewall riots “marked the beginning of the modern lesbian and gay movement,” because he claims “revisionist historians are recovering the history of lesbian, gay and transgender activism preceding Stonewall.”26 Contrasting Cava, William B. Turner praises Fejes more than criticizes him. Turner lauds Fejes for producing the “first scholarly account of Anita Bryant’s infamous Save Our Children campaign in 1977” and how Fejes “does a fine job of explaining the concepts from his home discipline without lasping into jargon.”27 Turner believes that the title of the book was a little too ambitious calling itself the “origins” of America’s debate on homosexuality, but Turner writes that the book will “benefit any historian of the post-World War II United States.”28

Fejes takes his time introducing the topic of homosexuality and the campaign struggles in the 1970s by including a chapter to explain the history that happened before the campaigns of 1977 and 1978. He also defined many terms or periods that readers could be unfamiliar with, like the term “fairy” which referred to “effeminate, weak, and soft” homosexual men.29 These definitions help readers understand new terms. Sometimes, he began his chapters with background information, like in the chapter, “Gay Rights Come to Miami.” The first few pages were on Miami in general and then there was a shift back to the 1930s and what Miami was like back then. This is somewhat confusing to readers because the shift is not fluid, but rather abrupt. However, Fejes continually does well providing information about the opponents of homosexuals, especially Anita Bryant. Fejes provides information of both sides. For example, he specifically states the reasons why Anita Bryant and her followers opposed homosexuals and their many campaigns, including Save Our Children. He also describes the different opinions within homosexuals. Fejes is very skillful in delivering information that is not too overwhelming but not too general.

In Gay Rights and Moral Panic, Fejes describes the Sixties as “a period of political and social upheaval in which many established legal, cultural and social regulations and norms were being challenged from a variety of sources.”30 The 1970s was a continuation of the 1960s as described by Fejes because the 1970s was a period of protests and campaigns for gay rights, and gay rights were first brought up and challenged in the 50s and 60s. Although Fejes does not directly state that the sixties were a continuation of the 1970s, he does mention that to understand the 1970s campaigns, readers must know the sixties, implying that the 60s continues on to the 70s. He describes the 1970s as a time of severity by focusing on Miami. He says that “by the mid-1970s Miami’s tourism-based economy was in a serious decline” and “by 1977 once-glamorous Miami Beach was being described by Time magazine as a ’geriatric ghetto’ and a ‘seedy backwater of debt-ridden hotels.’”31 During 1973-1975, recession hit Miami and “over a hundred bombs were exploded in Miami.”32 Many people thought their economic situations would improve in the 1970s but the level of poverty and unemployment stayed relatively the same. While the economy stayed the same, social values had been changed a bit because with Carter’s presidency, many Southern Baptists hoped that there would be a “return to the traditional American social values that had been so challenged by the social and cultural radicalism of the 1960s and the early 1970s.”33 Fejes also mentions on the eighth anniversary of the Stonewall Riots in 1977, the the typically optimistic atmosphere was replaced by angry protestors. There were demonstrations in San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, Atlanta, Seattle, Cleveland, and other cities. By providing information on these marches, Fejes shows that the 1970s was not a time of peace, but a time of protests and also bad economic conditions in parts of America.

Homosexuals had to deal with incredible amounts of discrimination not only in the 1970s, but also before and after. Fejes writes this book to not only provide two different views on gay rights, but also to show the struggles that homosexuals had to endure to find their way into society. Yet the point Fejes makes at the end of his work is that even after all their hard work, “the lesbian and gay community had achieved visibility, not legitimacy.”34

Footnotes:

- Fejes, Fred. Gay Rights and Moral Panic: The Origins of America’s Debate on Homosexuality. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. 19.

- Fejes, Fred. 2.

- Fejes, Fred. 12.

- Fejes, Fred. 13.

- Fejes, Fred. 17.

- Fejes, Fred. 29.

- Fejes, Fred. 45.

- Fejes, Fred. 53.

- Fejes, Fred. 62.

- Fejes, Fred, 63.

- Fejes, Fred. 79

- Fejes, Fred. 94.

- Fejes, Fred. 99.

- Fejes, Fred. 159.

- Fejes, Fred. 183.

- Fejes, Fred. 188.

- Fejes, Fred. 192.

- Fejes, Fred. 224.

- Fejes, Fred. 228.

- Fejes, Fred. 228.

- Fejes, Fred. 77.

- Fejes, Fred. 228.

- Fejes, Fred. 9.

- Fejes, Fred. 229.

- Cava, Peter. “Gay Rights and Moral Panic: The Origins of America’s Debate on Homosexuality by Fred Fejes.” The Journal of American Culture 32. 4 (2009): 350.

- Cava, Peter. “Gay Rights and Moral Panic: The Origins of America’s Debate on Homosexuality by Fred Fejes.” The Journal of American Culture 32. 4 (2009): 350.

- Turner, W.B. “Gay Rights and Moral Panic: The Origins of America’s Debate on Homosexuality. By Fred Fejes. (New York: Palsgrave Macmillan, 2008. X, 280 Pp $79.97, ISBN 978-1-4039-8609-4).” Journal of American History 96.3 (2009): 928-29.

- Turner, W.B. “Gay Rights and Moral Panic: The Origins of America’s Debate on Homosexuality. By Fred Fejes. (New York: Palsgrave Macmillan, 2008. X, 280 Pp $79.97, ISBN 978-1-4039-8609-4).” Journal of American History 96.3 (2009): 928-29.

- Fejes, Fred. 12.

- Fejes, Fred. 27.

- Fejes, Fred. 59.

- Fejes, Fred. 61.

- Fejes, Fred. 86.

- Fejes, Fred. 228

4 - 4

<

>