The Struggle for Peace

By David Lee

Lawrence Wright

Lawrence Wright graduated from Tulane University in New Orleans and received an M.A. in Applied Linguistics at the American University in Cairo, where he later taught English. Wright began his writing career as a reporter at the Race Relations Reporter in Nashville, Tennessee. Wright worked as a writer at Texas Monthly, Rolling Stone, and finally, The New Yorker.

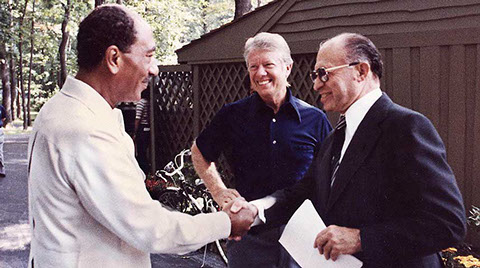

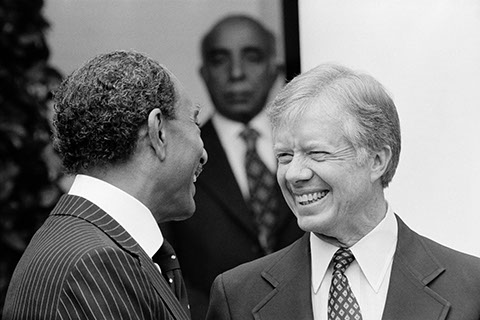

Throughout the 1970s, relations between Egypt and Israel—two major nations of the Middle East—rapidly deteriorated. Due to several destructive events, such as the Six-Day War, the War of Attrition, the Yom Kippur War, and the 1978 South Lebanon Conflict, hatred between the two nations dramatically increased in only a few years. This increasing level of discontent between the Arabs and the Israelites compelled United States President Jimmy Carter to invite two world leaders—Menachem Begin, prime minister of Israel, and Anwar Sadat, president of Egypt—to the presidential retreat Camp David in an attempt to broker a peace agreement between the two nations. If not for Carter’s drastic actions, conflicts between the two nations would have continued to escalate, for “hatred is so much easier than reconciliation; no sacrifices or compromises are required.”1 This shockingly accurate statement, from Lawrence Wright’s compelling work, Thirteen Days in September: The Dramatic Story of the Struggle for Peace, summarizes the history of Egyptian-Israeli relations. In his book, Wright meticulously discusses the fragile peace process, providing an explanation for the origin of the Camp David Accords through a day-by-day analysis. Combining politics, scripture, and the participants’ personal accounts into a powerful story, Wright provides a detailed description of the events that transpired in the 13 days.

Setting the stage for discussion, Wright starts by detailing the life of Jimmy Carter, the president of the United States of America during the Camp David Accords. In the prologue, Carter’s life before his presidency—his childhood, his terms as governor of Georgia, and his time at a US Naval Academy—is revealed through short recollections of his past. Wright also reveals key events of Carter’s past that clearly shaped his behavior during his presidency. For example, Carter’s experience with extreme racism in Southwest Georgia revealed to him the dangers of racism and discrimination, influencing him to attempt to spread relief equality to all. Wright then shifts to the backgrounds of the two other major figures in the book: Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin, the friendly President of Egypt and the perverse Prime Minister of Israel, respectively. These two leaders came together in an attempt to resolve the major Egyptian-Israeli conflicts of the Middle East. After the first short discussion of the summit between the three leaders, Menachem Begin’s extreme stubbornness made Carter realize that the Israeli Prime Minister probably had no “intention of going through with a peace treaty.”2 On the second day of the summit, Sadat revealed his proposal for the peace accords—a document titled The Framework for Peace. However, this uncompromising Egyptian proposal greatly angered Menachem Begin and the other Israeli delegates, for the document allowed no options for the Israelis.

When the third day arrived, Begin and Sadat began quarreling over a list of issues: “Sinai, settlements, an independent Palestinian state, Palestinian autonomy, Israeli presence in the West Bank and Gaza,” and many others.3 Finding no way to resolve these issues, the two men nearly left the summit, stopped only by President Carter’s begging. After this tense moment, Wright lightens the mood by giving a brief history of Jimmy Carter’s relationship with his loving wife, Rosalynn. When Carter awoke on the fourth day, he learned that “Sadat was preparing to leave, and Begin was drawing up a list of reasons why the summit had failed.”4 Although he had previously only cast himself as a facilitator, Carter now realized that the summit would fail unless he personally interfered and assisted Begin and Sadat by drafting his own document—the American Proposal. In all these chapters, brief and concise snippets of Egyptian and Israeli history are scattered among the events depicted in the book. With the start of the fifth day, Wright acknowledges the cause of many of these issues—Israel’s overwhelming victory in the Six-Day War of 1967. To quickly provide an American position on the discussion, the team of American delegates worked through the fifth day, finally producing a list of approximately “thirty items that [Carter] called ‘Necessary Elements of Agreement.’”5 This list of absolute necessities—intended to be submitted the following afternoon—including an end to war and permanent peace, allowed the American team to focus important or realistic goals. The next day, Carter led a trip to Gettysburg National Military Park in an attempt to remind the two stubborn leaders of the dangerous consequences that would result from a failed peace process. Although this trip triggered the emotions of the two leaders, tensions between Begin, Sadat, and Carter quickly returned when Carter presented the drafted American proposal to the Israeli Prime Minister. Angered by the demands of the American proposal, Menachem Begin raved at the American delegates. Scared by these series of events, Carter began “to have doubts about Begin’s sanity.”6

On the seventh day of the summit, Sadat and Carter debate the issue of Begin’s stubborn and indifferent nature. During this heated discussion, Carter finally accurately identified one of the most controversial topics of the debates—settlement and ownership of the Sinai Peninsula. After failing to reach a conclusion, Anwar Sadat stormed off, and returned the next day with the intent to leave again. Begin, who had also “ordered his delegation to issue a declaration that the talks were at an end…, had already given up on the summit.”7 Eventually, however, Carter was once again able to persuade the two impulsive leaders to attempt to compromise for a few more days. Throughout the next few days, Carter urgently discussed three major topics, the Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip and West Bank, and the city of Jerusalem, with Begin and Sadat. However, these next few days proved to be futile, for even when Sadat agreed to meet with the other Israeli delegates, the stalemate remained. At the end of the 10th day, Carter had burned out; he was simply too tired to continue on and now believed that he had failed.

The next day, Camp David held no emotions other than “total gloom and utter exhaustion.”8 In a final attempt to at least end the failed conference in a dignified fashion, Carter rushed out to meet Sadat, who was dressed for travel and waiting for his helicopter to arrive, and surprisingly convinced him to stay until Sunday—the originally appointed final day. Through a powerful speech, Carter was able to use his friendship with Sadat to convince him to stay until the end, as long as Carter signed a letter saying that “if either party rejected a portion of the accords, the entire agreement would be null and void.”9 Realizing that he would be the scapegoat if the peace accords failed, Begin then began trying to solve the issue of Sinai by lowering his demands. After hours of discussion, Carter finally saw the beginnings of a real peace accord. This hope, however, was shattered when Begin suddenly burst into rage over the topic of Jerusalem. A holy land to the Israelis, Jerusalem was the nation’s capital, and the Israeli team refused to give up the city. Through emotional monologues, heated discussions, and even enraged threats, Carter eventually convinced Begin to agree to the propositions placed before him. Camp David was finally over. A few hours later, in front of Congress and the public, the three leaders revealed two crucial documents, “The Framework for Peace in the Middle East” and “The Framework for the Conclusion of a Peace Treaty between Egypt and Israel.” These two documents, which dealt with issues including the ownership of the West Bank and Gaza, the autonomy of Palestine, and settlements in the Sinai Peninsula, were both readily signed by the three exhausted, but relieved men. Jimmy Carter, Anwar Sadat, and Menachem Begin had saved the future of the Middle East.

Throughout the book, Wright continually argues for the importance of Carter’s role in the Camp David process. Many historians prior to Wright tended to emphasize the roles of the leaders of the two conflicting sides—Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat—but often overlooked the critical role that Carter undertook at the summit. Although Carter was the most crucial member of the summit, his hard work was ignored when only “Sadat and Begin were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize” a month after the Camp David summit.10 Although it is true that Carter came to Camp David “under the spell of an illusion, seeing his role as that of a facilitator,” he did realize that the hostility between Begin and Sadat prevented them for working together fairly.11 When Carter eventually presented the first American draft of the agreement, he took upon himself a greater role—that of a catalyst to force Begin and Sadat to compromise and work together. Noticing the lack of respect for Carter’s efforts in the Camp David Accords, Wright wrote Thirteen Days in September to emphasize the relevance and utmost importance of Carter’s role at the summit.

As an extremely popular author, screenwriter, playwright, and a staff writer for The New Yorker magazine, Lawrence Wright is widely known for his ability to dramatize historical events. Having written many other dramatic historical works, such as The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11, In the New World: Growing Up with America, and Saints and Sinners, Wright may have been influenced by his tendency to dramatize events. Also, Wright was very fondly acquainted with Arabic culture, having lived in Cairo for over two years. This emotional sentiment towards Egypt became obvious in his writing of Thirteen Days in September, where Anwar Sadat and the Egyptian team were seen as the “good guys,” while Menachem Begin and the Israeli team were often see as the “bad guys.” Additionally, Wright’s credibility as a historical nonfiction author has been tainted in the past, for his book, Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood and the Prison of Belief contained numerous inaccuracies. A website dedicated to correcting the falsehoods of Lawrence Wright’s book on Scientology even revealed that “Wright’s book has gone unpublished in the U.K. after his publisher there was made aware of the books’ errors.”12 Written in 2014, Thirteen Days in September embodies a style influenced by the attitudes of many teenagers today. Historians all around the world know that many students dislike reading boring historical nonfiction works, so writers like Lawrence Wright turn to dramatic and intense historical thrillers to effectively teach historical events to students and teenagers. Additionally, the love for entertainment and plays in the 21st century also contributed to Wright’s creation of this work, for Thirteen Days in September was originally written as a dramatic play, Camp David.

In a New York Times book review of Thirteen Days in September, political columnist Joe Klein critiques the book, emphasizing both the strengths and weaknesses of the work. Klein starts his critique of Lawrence Wright’s book by describing it as “a magnificent book with an unusual provenance.”13 Wright originally wrote the work as a dramatic play, Camp David, but eventually wrote a book adaptation of the play upon realization that the Camp David process was “more than just a stirring drama; it was a hinge in the history of the region, and a tutorial in negotiating strategy.”14 Although Klein shows his appreciation for Wright’s detailed day-by-day account of the event, Klein enthusiastically praises the interspersed accounts of Egyptian-Israeli relations, dating back to the story of Exodus. Klein then continues to commend Wright’s knowledge of the three major leaders—Carter, Sadat, and Begin—not just as political figures, but also “exemplars of the Holy Land’s three internecine religious traditions.”15 Another review, written by Ellen Warren for the Chicago Tribune, also praises the “seamless, compelling back grounding of the region’s violent history and the enmities and peculiarities of the players” who arrived at the summit.16 Warren, a former Middle East correspondent, also applauded Wright’s historical accuracy and meticulous attention to detail. These two critical reviews of Thirteen Days in September both did not have much criticism. Instead, they commended Wright’s historical accuracy, his dramatization of the event, and his dispersion of context and outside information.

Few books have discussed the dramatic events that led to the Camp David Accords, but Lawrence Wright’s historical nonfiction thriller looks into the subject in great detail. In Thirteen Days in September, Wright picks the summit at Camp David apart, studying and analyzing each day individually. Through this meticulous process, he effectively points out the events of the peace process while providing a thrilling and suspenseful account of the struggles that the three world leaders faced. In addition, Wright also provides an extensive amount of contextual information that allows readers to understand the events of the story. However, these glimpses into the past were often extremely long and provided much more information than necessary. Often, Wright would spend many pages discussing a single event—such as “President Gamal Abdel Nassar, Anwar Sadat’s predecessor”—that did not have much relevance to the peace process.17 Despite these drawbacks, Thirteen Days in September was a very enjoyable read, both informative and exciting. Wright also creates a new perspective towards the United States President at that time, Jimmy Carter. Although Carter is widely known for his humanitarianism and his enthusiasm for equality today, he is not typically given much credit for his efforts at this summit. In this book, however, Carter’s role during the Camp David conferences is strongly emphasized. Overall, Lawrence Wright’s Thirteen Days in September provides a riveting yet scholarly account of the importance of Carter’s role in the creation of the Camp David Accords.

Obvious through the events of the book, Wright definitely emphasizes the 1970s as a time of severe crisis in the United States. Although Thirteen Days in September did not focus on domestic issues regarding the country itself, it does focus on the United States involvement in Middle East affairs. On Carter’s “first day in office, he announced that peace in the Middle East was a top priority.”18 Despite the warnings that his advisors gave him, Carter still proceeded with the summit, for he understood the disastrous consequences that wars in the Middle East would bring. Although the Camp David Accords eventually did lead to peace treaties between Egypt and Israel, the difficulties that Carter encountered at the summit revealed the actual severity of the issues plaguing the Middle East. Furthermore, Wright also briefly lists many “issues that had piled up while Carter had devoted himself to making peace in the Middle East” such as the increased levels of stagflation.19 In this sense, Wright supports the claim that the 1970s was a time of severe crisis in the United States. In addition, Wright also portrays the 70s as a continuation of the 60s in terms of foreign affairs. In the 1960s, the U.S. was already heavily involved in foreign affairs, primarily with the Soviet Union and its Communist satellites. When the late 70s arrived, Carter realized that involvement in the foreign affairs needed to extend to the Middle East. Thus, Carter invited Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin to attend the Camp David Peace Conference in an attempt to achieve a permanent peace between the two nations. Through this, Wright reveals how the 70s was a direct continuation of the 60s.

Although Wright primarily analyzed the conflicts and issues between Egypt and Israel, his book Thirteen Days in September actually takes a broader look at the dangers of hatred and war in general. Wright’s statement that hatred is much easier than compromise proves true for all of history. Although hatred is obviously the simpler path, Wright reveals that the rewards reaped from a successful peace are more than worth the trouble of creating the peace. Several times throughout the summit, both Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat desired to leave. However, all three leaders eventually agreed to compromise when they were reminded of the dangers of a failed peace treaty. Although the Camp David Accords succeeded in bringing peace between Israel and Egypt, “it’s impossible to calculate the value of peace until war brings it to an end.”20

Footnotes:

- Wright, Lawrence. Thirteen Days in September: The Dramatic Story of the Struggle for Peace. New York City: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014. 124.

- Wright, Lawrence. 82.

- Wright, Lawrence. 117.

- Wright, Lawrence. 148.

- Wright, Lawrence. 198.

- Wright, Lawrence. 229.

- Wright, Lawrence. 247.

- Wright, Lawrence. 312.

- Wright, Lawrence. 306.

- Wright, Lawrence. 357.

- Wright, Lawrence. 372.

- Johnson, Creaton. “How Lawrence Wright Got it So Wrong.” Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood and the Prison of Belief. Church of Scientology, 8 Jan. 2015. Web.

- Klein, Joe. “Elusive Peace: ‘Thirteen Days in September,’ by Lawrence Wright.” The New York Times 9.11 (2014).

- Klein, Joe. “Elusive Peace: ‘Thirteen Days in September,’ by Lawrence Wright.” The New York Times 9.11 (2014).

- Klein, Joe. “Elusive Peace: ‘Thirteen Days in September,’ by Lawrence Wright.” The New York Times 9.11 (2014).

- Warren, Ellen. “Review: ‘Thirteen Days in September’ by Lawrence Wright.” The Chicago Tribune 9.18 (2014).

- Wright, Lawrence. Thirteen Days in September: The Dramatic Story of the Struggle for Peace. New York City: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014. 156.

- Wright, Lawrence. 7.

- Wright, Lawrence. 350.

- Wright, Lawrence. 377.

4 - 4

<

>