I'm Not Going to Take This Anymore!

By Hannah Kwan

Dominic Sandbrook

Dominic Sandbrook is a British historian. He has a Masters degree in history at the University of St. Andrews and a PhD from Jesus College in Cambridge. He has written several books on American history, including one of his most popular books on Eugene McCarthy.

During the 1970s, the aftermath of the Cold War and changing times created turmoil throughout the decade. In his work, Mad as Hell: the Crisis of the 1970s and the Rise of the Populist Right, Dominic Sandbrook describes the condition of the American people during a time of change, while conservatism struggled to remain in American culture. With changing values, various foreign conflicts, and new culture, the 1970s was a turning point for American culture and politics, setting up the beginnings of modern society. Beginning with the fall of Nixon, Sandbrook chronologically follows the presidents that served during the decade, with Nixon, Ford, Carter and the inauguration of Reagan as well as the economic and social problems during the 70s. Sandbrook describes the atmosphere of the 1970s, that “for the first time in more than a generation, ordinary Americans genuinely doubted that tomorrow would be better than today”.1 The uncertainty of the American people paved the way for the return to conservatism, a response to the liberalism during the 1960s. Throughout his work, Sandbrook delineates the history and politics of the 1970s, and how conservatism manifested itself in American pop culture.

Sandbrook depicts the beginning of the 1970s with the fall of Nixon and rise of Ford. Nixon’s dishonesty with the American people in the Watergate scandal left a lasting impression on the American people about authority. After Nixon’s resignation, trust in authority slowly declined. When Ford took Nixon’s place, he was not popular among the people and Ford himself had a dreary outlook on his upcoming presidency. Along with Ford’s attempts to alleviate the inflation with his “Whip Inflation Now” policy, he also tried to cut taxes and welfare programs in what Sandbrook calls a “new realism”.2 During the beginning of the 1970s, evidence of the previous decade remained in the changing values and controversial topics, such as sexuality, racism and crime. The increasing rate of divorce, teenage pregnancies, and acceptability of premarital sex indicated a declining morality. For example, the television show, All in the Family, displayed a dysfunctional family and talked about controversial topics such as homosexuality, racism and the woes of the working class. However, Sandbrook mentions that the majority of America was appalled by the unorthodox behavior, and is often called the “silent majority”.3 Films reflected the times; Dirty Harry (1971) represented the traditional values that were starting to fade in the younger generation and The Godfather (1972) showed the ethnic revival. Star Wars (1977), created by George Lucas, fed the “public thirst for heroism”, Lucas himself admitting the film to be highly conservative. After the end of the Vietnam War, America turned back to isolationism with less faith in their country, films like Star Wars “recaptured the crusading spirit”, something people thought they had lost after the war.4 However, war was less appealing to the general public. Americans leaned toward the more sensitive feeling, rather the harsh realities of war.

Sandbrook credits the return of conservatism and election of Carter and Reagan to the development of the South, which had begun to change rapidly. After the Brown v. Education court ruling was passed, segregation had remained throughout most Southern schools. The school systems found ways to segregate with zones, because African-Americans were deliberately separated from white communities. In attempts to solve this problem, the Supreme Court passed Morgan v. Hennigan, which enforced a busing plan that divided the school districts so the schools would be properly integrated. However, the plan was not popular and violence was involved and an antibusing movement was created. Despite the struggles with racism and segregation, the South was booming with new industries and culture, an area called the Sunbelt. The South was growing with new industries and pop culture, country music, football and the famous Dallas Cowboys gave it a new identity, the New South, the process known as “Southernization”.5 After Ford’s failure to improve the American society, people looked to another president in hopes of returning to conservatism. Jimmy Carter was a farmer, grew up in the Plains and seemed like the epitome of an American citizen. Carter defeated Ford, and Sandbrook credits his win to the support he received from the New South, where the majority were Republicans. However, Carter struggled to stimulate economic growth and supply more jobs and food, energy and labor prices continued to rise. As America entered the 70s, the return to conservatism also meant a revival of religion, especially evangelism. And while it was mainly conservative, there were also remains of the counterculture of the 1960s. There was a search for something spiritual, a focus on self-improvement and self-expression.

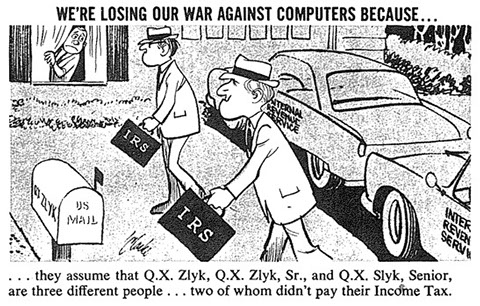

Sandbrook addresses the diversity and feminist movements of the 1970s. Blacks were starting to be integrated into society, evident in the growth of the black middle class. There was no explicit racism; however, the black community, as well as the new wave of immigrants, were minorities in the American population. While some of the women advocated new movements for more rights, the majority opposed many of those changes, some including the Equal Rights Amendment, gay rights, and abortion. Phyllis Schlafly was an active antifeminist, and played a huge role in the rejection of the Equal Rights Amendment. Sandbrook also discusses the reality of California, where the “superficial glamour of California life” was only covering the underlying anxiety.6 The rate of the unemployed was rising, and the economy was declining. A tax revolt prompted the famous Proposition 13, which promised to reduce taxes. However, it would reduce a significant amount of revenue from the cities, counties, and school districts. Sandbrook explains that the tax reduction was also a sign of conservative revival, “offering Republican politicians a new set of ideas, a new vocabulary and a new faith”.7

Sandbrook emphasizes the importance of Carter’s inability to deal properly with Afghanistan and Iran, and how it opened the door to Reagan. In reaction to the Soviet Union invasion of Afghanistan, Carter asked for a required draft and an increase in defense spending, the change in foreign policy also was to acquiesce the American belief that they were behind the Soviet Union in technology. In addition, the Iranian hostage crisis occupied most of Carter’s last few months in office, all the way up to the end of his campaign for a second term in office. Sandbrook then describes the characteristics of conservatism, the ordinary American’s who were a part of the New Right movement. Ronald Reagan emerged from the New Right movement as a candidate for the presidency and charmed the American people with his acting experience, his flexibility and moderation. While Reagan was hardly a fundamentalist, he advocated for the Moral Majority and assured the American public, “I endorse you and what you are doing” and Sandbrook agrees, “the soldiers of God had found their general”.8 Reagan defeated Carter in the election of 1980, though Sandbrook credits his win to the problems that prompted Americans to turn toward conservatism including the failures of Nixon, Ford, and Carter and the Iranian hostage crisis. Sandbrook ends with Carter’s defeat, a scene from the White House as Reagan celebrates his win, and the dire situation as the 1970s ended.

Sandbrook explains, in the preface, that title of his book, Mad as Hell, was from a film Network, where Howard Beale says, “’I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore!’”9 The author uses this to introduce the main thesis of his book, a history on the 1970s from the point of view of the silent majority, an America that was different and more mature than the previous decades. Sandbrook writes, “the passions of the 1960s seemed to have given way to the cold, hard realities of retreat abroad and retrenchment at home.”10 He sets the scene for why and how Reagan and conservatism became so popular in the 1970s, as wells as its influence on the society and culture. Sandbrook follows each president, starting with the fall of Nixon, to show the disparity that each president had to deal with, and how conservatism became the answer to America’s problems. With all the troubles during the 1970s, conservatism made its way back into pop culture, and influenced the desires of the American people.

Sandbrook’s nationality has an effect on the perspective and opinion on America’s crisis during the 1970s. His outside point of view allows him to consider the events of American history without a strong bias in political preferences. Evident in his writing, Sandbrook writes from a mostly neutral perspective, fairly judging the effect conservatism had on America’s society. Mad as Hell1 was written in 2011, and Sandbrook’s interpretation of the 1970s is a recent one and views the decade nearly fifty years later. By doing so, the author is able to see the effects of the period in our modern culture and to take a look at the decade with a little less bias.

Bradford Martin from the Journal of American History seemed to be impressed by Sandbrook’s work, especially because of its prose. Martin writes that the author “identifies populism as the unifying theme behind a disparate aggregation of contentious forces”.11 He commends the author’s ability to use language and thoroughly articulate his main ideas. Martin focuses on Sandbrook’s writing on the crisis of the 1970s, and his description of Carter. Martin does critique the author’s inclusion of popular culture references and background, claiming that it can take away from his argument, seemingly irrelevant. He was surprised when the author did not give such applause for Carter’s accomplishments as he would expect, but instead, writes about Carter’s incompetence to deal with the problems during his term in office. Lastly, Martin mentions that the length of the book might turn away some people, yet a perfect book to benefit the Republicans and Tea Party today.

Sasha Abramsky not only reviews Dominic Sandbrook’s work, he also uses it to comment on society and the manifestations of the problems that Sandbrook mentions throughout his work. Abramsky starts by explaining the current situation of American politics and then applies Mad as Hell: The Crisis of the 1970s and the Rise of the Populist Right, explaining how it helps explain how American politics has become so degenerate through the media and other influences. He goes on to give Dominic Sandbrook credit, acknowledging his other works and impressive resume and validating his work. Abramsky begins to disclose his opinions of the book, “the scattershot approach is occasionally overwhelming” and that “one wishes that Sandbrook had also interviewed the participants directly” but is quick to alleviate the criticisms with praise and understanding for Sandbrook’s reasoning in his choices.12 With a liberal bias, Abramsky agrees with Sandbrook, that all the disparity of the 1970s led to Reagan’s election, and mentions that about twenty-five percent of American’s voted for Reagan. Again, he connects the dire situation in the 1970s to today, comparing the two periods, which are similar in its crises and public opinions.

Sandbrook presents a wholly satisfying work, cleverly weaving cultural and economic occurrences, producing a clear depiction of the 1970s. The upheaval and troubled American people are expressed through each president’s struggle to stabilize the economy and adequately deal with foreign countries. Sandbrook brings in aspects of the pop culture of the 1970s, mentioning films, songs, television shows, tying each of them into the crisis, revealing the effect of the growing conservatism. He introduces the economic crises through each president’s dealing with each. Through each election and struggle to resolve impending problems, Sandbrook provides his audience with a good feel for the decade, appealing to their pathos with narratives of Nixon’s peace of mind after his resignation, Ford’s nervousness before his inauguration, and Carter’s actions after his defeat from Reagan. He brings the presidents back to life, taking the reader inside the White House and describing the reality of America’s troubled situation. At the end of his book, Sandbrook describes a picture of a pair of party crashers at the Reagan inauguration celebration, but get caught, and finally, “the illusion was broken, and they were back outside, shivering with cold as Washington toasted the new era”.13 Sandbrook cleverly reveals a jubilant Reagan in the White House, yet describes the reality of the end of the 1970s. While conservatism may have recovered traditional values and boosted morale, the reality of end of the decade was far from Reagan’s enthusiasm and Sandbrook leaves the audience with a dire picture, emphasizing the disarray America was left in.

On the crisis of the 1970s, Dominic Sandbrook approaches the topic chronologically, looking at the period economically, politically and socially. Economically, Sandbrook focuses on the oil crisis and growing inflation. The food and gas prices soared in the 70s. Politically, he studies each president from Nixon to Reagan, and their struggle to deal with foreign and domestic policy as well as their campaigns and personal backgrounds. Socially, Sandbrook brings in elements of pop culture, revealing the extended affect of the chaos of the decade on films, television, music and sports. The Dallas Cowboys won the Super Bowl and reasserted “traditional American manliness at a time when the headlines were full of American impotence”.14 Bruce Springsteen’s characterized the decade, “his stories of alienated youngster with dead-end jobs in crumbling towns made perfect sense to millions across the nation.”15 Sandbrook sees the crisis of the 1970s as a crisis that affected all theses aspects of America during the decade. He steps back and takes a panorama of the chaos in the flailing economy, the troubled presidencies and the changes in the American culture. He focuses on the minorities and their progress and opposition that resulted from the turmoil of the decade – the development of the black middle class and roles of women. In a time of crisis, Sandbrook sees the return to conservatism as a result of the confusion as well as mild change in the treatment of minority groups and shift in the mood of the American people from a positive one of the 60s to a depressing one in the 70s. Sandbrook himself explains that the 60s set up the 1970s, the drastic changes in morals and status of minorities continued into the 70s, and widely influenced the culture that was produced. He writes, “many things that we imagine started in the 1970s … actually had their roots in earlier decades.”16 And while the problems started brewing in the 1960s, they took hold in the 1970s – the discontent a catalyst for change.

Dominic Sandbrook’s Mad as Hell: The Crisis of the 1970s and the Rise of the Populist Right is more than a book on the chaos of the 1970s. It’s a book on “the vast majority who did not join protest marches or political groups” and the culture that was the beginning of the modern-day society.17 From his work, readers can see the origins of modern conservatism and its lasting effect on American culture and the turmoil that rocked the 70s and changed America forever.

Footnotes:

- Sandbrook, Dominic. Mad as Hell: The Crisis of the 1970s and the Rise of the Populist Right. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011. Xii.

- Sandbrook, Dominic. 45.

- Sandbrook, Dominic. 50.

- Sandbrook, Dominic. 102.

- Sandbrook, Dominic. 137.

- Sandbrook, Dominic. 276.

- Sandbrook, Dominic. 289.

- Sandbrook, Dominic. 360.

- Sandbrook, Dominic. X.

- Sandbrook, Dominic. Xii.

- Martin, Bradford. “Mad as Hell: The Crisis of the 1970s and the Rise of the Populist Right.” Journal of American History. Oxford University Press, 2011. Web. 28 May 2015.

- Abramsky, Sasha. “Anger Management.” Columbia Journalism Review, Feb. 2011. Web. 26 May 2015.

- Sandbrook, Dominic. 408.

- Sandbrook, Dominic. 324.

- Sandbrook, Dominic. 82.

- Sandbrook, Dominic. Xi.

- Sandbrook, Dominic. Xiii.

4 - 4

<

>