Renovating 1970s Sexual Culture

By Isabelle Lee

Elana Levine

Elana Levine graduated from the University of Wisconsin with a Ph. D. in Communication Arts. She has taught several courses about media culture, gender and popular culture, and television mass media in American society. Not only did she write Wallowing in Sex, she had also published Legitimating Television: Media Convergence and Cultural Status.

How did modern day television shows evolve to be so full of sexual innuendos? Following the counterculture of the 1960s, television of the 1970s explored a more contemporary vision of sex and gender. Major broadcasting stations were responsible for the further development of sexual culture on air. Contrary to popular belief, the transformation of television in the 1970s was “not repression to liberation but a series of struggles to define what sex meant.”1 Suggestive sex, rather than explicit sex highlighted television during the decade. In Wallowing in Sex: The New Sexual Culture of the 1970s American Television, Elana Levine exposes the ways that sex culture on television changed traditional American culture as a result of competition between ABC, CBS, NBC, and opposition from the women’s liberation movement, the gay-rights movement, and lesbian activist movement.

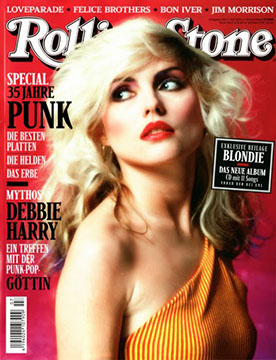

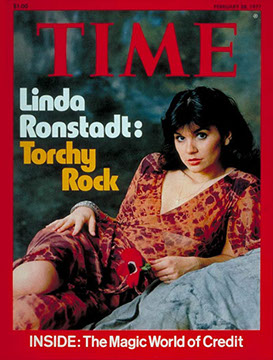

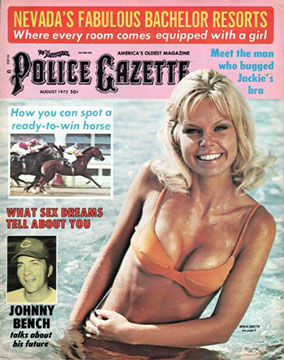

Television’s culturally impacted American society through a chain of events. The three major broadcasting companies, ABC, CBS, and NBC, commercialized sex in their struggle to “outsex” the other. Public audiences embraced the increasing amount of shows with models in tight clothing and low camera angles, feeding the big three’s motivation to focus more on open concepts of sex on television. The women’s liberation movement, gay-rights movement, and later lesbian activists would criticize this sudden influx of the new sexual culture on television, bringing about questions regarding morals and ethics. ABC, CBS, and NBC began catering their shows to young audiences, incorporating more sexual references in daytime sitcoms, comedies, and dramas. These three broadcasting companies began to challenge the status quo of content on television: “CBS’s hit sitcoms continued to challenge TV taboos by using sex as one of many politically charged themes.”2 In the early 1970s, two forms of sex presented on television were kiddie porn and adult porn. Fred Silverman, central to understanding kiddie porn, helped ABC programs increase their ratings through incorporating sexual humor in their kid-friendly comedies. Adult porn became chained to the term “jiggle tv” as the amount of female sex symbols increased in the show business; new liberalized sexual representations were underway. Not everyone accepted the sexual spice on television. The development of a new MPAA ratings system was established categorizing shows and movies to warn parents of the level of explicit content. The government intervened to put restrictions limiting the intensity of sexual content in television shows, like restricting high amounts of sex talk shows on radio broadcasting.

Noticing that gradual acceptance of the new sexual culture on American television would not be accepted without some opposition, the television industry created the National Association of Broadcasters in 1923, which upheld a code that “forbid and allowed certain product categories for individual broadcaster decisions” in attempt to self-regulate itself.3 While sexual innuendos and more skin showing was increasing on television of the 1970s, broadcasters hesitated to venture more into controversial topics like bra advertising with live models and contraceptive promoting. Gradually, the popularity of the birth control pill encouraged women to have more sex, encouraging broadcasters to promote birth control and condoms to women to gain profit. The NAB television code deemed that content relating to contraceptives were unsuited for family audiences.4 Because television sex was targeting specific audiences, there was debate over the effects of television violence and sex on youth. Television of the 1970s exploited sexual content and social issues like teenage alcoholism and STDS, but ignored issues surrounding poverty and wage discrimination.

While films strayed away from contraceptive talk, many shows began to address a new perspective of lesbianism, traditionally treated as “evil,” by encouraging people to be more open and accepting. Many television shows began incorporating a number of races to address social issues, signifying that these issues were not specific to whites only. Despite the attempts of government to regulate of television broadcasting, the right of freedom of expression in the Constitution’s First Amendment made it not very effective.5 Movies prior to the 1970s were usually two hour long runs, but in order be more efficient and create a family viewing atmosphere, the three broadcasting companies switched to showing ninety minute movies. Television shows in the late 1970s “intended for mature audiences” used exploitation tactics to grab the audience’s attention but also limited the content to a “family medium.”6 In the 1970s, a new image of females with masculine personalities began to emerge. Instead of debuting explicit porn stars, show directors often related feminine attractiveness with internal strength and bravery. Television’s “New Woman” icons Wonderwoman and Bionic Woman developed during the 1970s reflected Rosie the Riveter, who symbolized the strength of femininity. A fresh form of feminism illuminated the 1970s; for the first time, television and American society began to explicitly promote heterosexuality.

Things are never as they appear on television. As objectified disguises, the focus on women’s new image represented their struggle to gain professional equality. Humor plagued sexual themes of 1970s television. ABC’s “Happy Days” referenced sex as a fun fact of life and “The Love Boat” transformed saunas into rooms of heterosexual flirting destinations.”7 American society began to throw away the perspective that gays and lesbians were malicious. However, one of the most controversial topics of the new sexual culture of 1970s television, rape, addressed a nationwide matter. General Hospital, a famous television series incorporating rape to address the 27,100 FBI reported rapes in 1967.8 It was clear to the audience that rape was motivated by hostility, not by sexual desire. The show emphasized how the rapist could also suffer from the traumatic event. Rape began to occur more frequently on television in the 1970s, and although it was meant to convey the social issue of rape, there were still those who thought that blending social issues and appeal to young people was dangerous. Feminist anti-rape movements formed as a response to the increased attention to rape in media culture. Television culture changed sexual morals, beliefs, and practices during the 1970s, powered by the fuel of paranoia, caution, and teenage sexual desires. The subculture of sex on television encouraged a moral panic over youth sexuality and developed into “common sense” of American sexual culture.

Levine argues that “TV was the most significant cultural form for the dissemination and acceptance of the monumental changes in sexual identities, practices, mores, and beliefs.”9 Throughout the book, sexual culture’s effect on television’s evolution is examined comprehensively. The dominance of heterosexuality over other sexual orientations rose because of the 1970s television culture. As the nation continued to develop, wages increased and had more time for leisure activities. Daytime television and primetime television were a crucial part of American society, as both show times casted different levels and forms of sexual integration. Public audiences had mixed responses. The status quo perception of sex had been altered as Americans began pushing the level of what was scandalous lower and lower. In fact, sex on television was generally not explicit, it was usually enveloped in comedy or drama. This helped American society embrace a more liberal attitude towards sex. Feminism movements garnered attention to a new image of women outside of their domestic responsibilities. Television creators operating within larger economic and political restraints shaped an American sex culture that was not too extreme, but rather well-defined.

Elana Levine majored in communication arts in the University of Wisconsin and developed a massive interest in media’s effect on American culture during the second half of the 20th century. Wallowing in Sex critically analyzes the “influence of major television broadcasting companies and significant television shows” that harnessed the evolution of the new sexual culture of 1970s television but did not, in detail, examine the public’s reaction to these changes.10 Levine has a PhD in communication arts, so it’s very likely that because of her immense knowledge of television media’s history, she wrote her book focusing on the internal changes within television culture instead of focusing on the public’s reaction of these changes. During the 1970s, a new subdivision of historiography developed, social history. This was a time of an increase of scholars, a time of tremendous focus on education and social culture, and a time when the women and gay-rights movements prospered. Beginning in the 1960s, sexual culture rose to prominence, and its effects on the 1970s was distinct. Television creators experimented with varied amounts of sexual innuendo and references and found the appropriate level with the help of criticism from not only the women and gay-rights movements, but also the hoi polloi’s reaction. Politically, new conservatism shaped the 1970s. However, socially the nation became more liberal. The growth of new ideas out of the social norm influenced Levine’s critical covering of the effect of sexual culture on television on American society.

Reviews of Wallowing in Sex: The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television agree that the 1970s was a decade of television network struggle to “contain the ongoing sexual revolution.”11 Television in the 1970s explored daring new perspectives of sexual culture and social issues. Whitney Strub from the Journal of the History of Sexuality writes that the book provides a prime “overview of tremendous importance for television historians.”12 Television’s legacy, however, is mixed; Strub argues that “while television helped normalize recognition of youth and queer sexuality…it also toned down any radical components, rendering counternormative sexualities palatable to mainstream audiences.”13 The popularity struggle between ABC, CBS, and NBC had clear effects on the quick integration of sexual culture on television. By the end of 1978, CBS’s tag line “turn us on and we’ll turn you on” precisely described television’s influence on the status quo. Frederik Dhaenens from Ghent University touches upon the main ways “which the networks integrated sexual imagery” by copying one another while “simultaneously criticizing their rivals’ methods.”14 Dhaenens notes that Levine writes in a straightforward and clear manner, allowing the readers to fully navigate the numbered forms of sexual culture on television. As a very detailed overview of sexual culture of television during the 1970s, it also offers “critical inquiry into historical processes of regulation, prohibition and shame which are affecting what can and cannot be displayed on screen.”15 Wallowing in Sex looks into several impactful television series with great detail, adding to the effective analysis of how most of modern day sexual culture developed from 1970s television culture.

Sex themed media during 1970s television is often overlooked and Levine arguably looks into the subject in great detail. While examining “female sex symbols, comedy-variety shows, and rape plots on soap operas,” Levine offers insight into how television entered into a more liberal phase.16 Hilary Radner from the University of Otago Dunedin states that Levine addresses the questions that a more liberated television culture tried to raise with a “degree of complexity and ambiguity difficult to come by in the more high-profile world of prime time.”17 This is a book that would attract television scholars and those interested in how media shaped the modern sexual outlook. The television industry did not develop the “New Woman” but instead formed a new view upon women. Instead of losing its audience with slightly controversial content, American viewers, especially youth, began to satisfy their curiosity. Levine does a decent job in defining the change of daytime and primetime television during the 1970s. Traditionally, shows that showed more trivial and sensitive topics were broadcasted in primetime. However as the big three broadcasting companies invested their time into their competition against each other, American society began to see adult shows that they would normally see at 11 pm during the daytime. This caused more attention to be focused onto the youth viewers, who had begun exploring their sexuality. Radner argues that the “author’s writing style often is uncomfortably pitched between journalism and scholarship” which can be seen when Levine sometime goes too far into detail about television shows.18 The title Wallowing in Sex can be a bit controversial and misleading, since it makes the book give off a sensationalist feel, but the subtitle, The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television adds a journalistic feel. Previously, historians had vaguely studied television’s effect on the phenomena that define the 1970s. Levine’s book provides an adequately informative outlook into television’s effect on American norms, specifically the sexual culture of the 1970s.

Wallowing in Sex does provide comprehensive information about top shows that made a huge impact on teenage drug abuse, delinquency, women as sex symbols and the sexual revolution itself. However, at times Levine deviated the from the purpose of her subject. Levine explained in great detail the full plot summary of General Hospital. While her purpose is to prove the point that rape scenes, if integrated correctly, can represent a concept not limited to its “immoral” connotation, with each page of text addressing the story plot, Levine loses strength of proving her point. That does not stop the book from covering sexually light topics, like the amount of skin to show on television, to darker and more disturbing topics like rape. The general overview of the history of what ABC, NBC, and CBS broadcasted prior to 1970 was very important to explaining the competition that arose in the 1970s between them. The competition mutually benefitted all of the “oligopolistic networks” in terms of bringing the new sexual culture to American television.19 By exploring darker sides of television, American culture began to become more aware of taboo social issues.

Although not explicitly stated, Levine believes that 1970s television had a tremendous impact on American society during a severe crisis. The book focused more on social changes that were affected by television culture during the 1970s, but also mentions several political factors that had helped bring change to the status quo of television broadcasting. New Conservatism had grown popular during the 1970s and the desire to be return to normalcy caused the US government to establish the NAB code to regulate what content was shown on television. However, Levine states in the beginning of her book that because people’s wages increased in the 1970s, they began spending more time doing leisure activities.20 The relationship between the reemergence of sexual culture in what began in the 1960s and continued to the 1970s and the severe crisis of the 1970s in America can be seen in two ways. The struggle of youth experimentation with the world and the amplified evolution of sexual culture on television can represent the internal struggle of the new generation’s journey to find their identity. It could also signify how American society generally wanted to break away from tradition and find a route out of the severe crisis through sexual immersion on television.

Transition from the 1960s to the 1970s resulted in the counterculture’s effects on 1970s television shows. This continuation of rebellion against the status quo helped fasten the new sexual culture’s influence on American society. In the 1960s, teens began experimenting with drugs and alcohol, and in 1970s television shows began addressing the social issue of teen alcoholism in hopes of discouraging drug and alcohol use.21 Tight clothing and the shortening of skirts fell into the 1970s as females began to explore their sexuality and feminism. The concept of feminism was revisited during the 1970s through television by emphasizing “female attractiveness and strength” in Wonder Woman and Bionic Woman.22 Alongside calls for female independence from domestic responsibilities, homosexuals were given a new connotation to their name. Through incorporation of humor into gay sitcoms, people became more tolerant of non-heterosexually oriented couples. In a broader view, if it wasn’t for the Counterculture in the 1960s and the feminism activists, women’s movement, and the gay-rights movement that had developed prior to 1970s, sexual culture on television may not have emerged to prominence as fast as it did.

Levine analyzes not only the effects of the struggle to be the best of ABC, NBC, and CBS on American television culture of the 1970s, but also how counteractive groups actually helped develop the new sexual culture of 1970s American television. CBS’s tag-line “Turn us on, and we’ll turn you on” highlights the attention to changes in sexual culture of television of the 1970s.23 Sexual culture of 1970s television played a major role in shaping modern American culture.

Footnotes:

- Levine, Elana. Wallowing in Sex: The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2007. 4.

- Levine, Elana. 29.

- Levine, Elana. 60.

- Levine, Elana. 67.

- Levine, Elana. 104.

- Levine, Elana. 113.

- Levine, Elana. 184.

- Levine, Elana. 210.

- Levine, Elana. 4.

- Levine, Elana. 6.

- Strub, Whitney. “Wallowing in Sex: The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television (review).” Journal of the History of Sexuality 19.2 (2010): 347-51. Web.

- Strub, Whitney. “Wallowing in Sex: The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television (review).” Journal of the History of Sexuality 19.2 (2010): 347-51. Web.

- Strub, Whitney. “Wallowing in Sex: The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television (review).” Journal of the History of Sexuality 19.2 (2010): 347-51. Web.

- Dhaenens, Frederik. “Wallowing in Sex: The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television30.2 (2010): 252-54. Web.

- Dhaenens, Frederik. “Wallowing in Sex: The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television30.2 (2010): 252-54. Web.

- Radner, H. “Wallowing in Sex: The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television. By Elana Levine. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007. Viii, 320 Pp. Cloth, $79.95, ISBN 978-0-8223-3902-1. Paper, $22.95, ISBN 978-0-8223-3919-9.).” Journal of American History 94.2 (2007): 627. Web.

- Radner, H. “Wallowing in Sex: The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television. By Elana Levine. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007. Viii, 320 Pp. Cloth, $79.95, ISBN 978-0-8223-3902-1. Paper, $22.95, ISBN 978-0-8223-3919-9.).” Journal of American History 94.2 (2007): 627. Web.

- Radner, H. “Wallowing in Sex: The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television. By Elana Levine. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007. Viii, 320 Pp. Cloth, $79.95, ISBN 978-0-8223-3902-1. Paper, $22.95, ISBN 978-0-8223-3919-9.).” Journal of American History 94.2 (2007): 627. Web.

- Strub, Whitney. “Wallowing in Sex: The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television (review).” Journal of the History of Sexuality 19.2 (2010): 347-51. Web.

- Levine, Elana. Wallowing in Sex: The New Sexual Culture of 1970s American Television. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2007. 10.

- Levine, Elana. 80.

- Levine, Elana. 148.

- Levine, Elana. 236.

4 - 4

<

>