Sending the Red Envelope

By Kris Kong

Min Zhou

Min Zhou was born in Zhongshan, China. Zhou is currently the Professor of Sociology at UCLA and also the founding chair of the University’s Department of Asian American studies. Other works she has published besides Contemporary Chinese America include, Asian American Youth and The Transformation of Chinese America.

Since the 1840s, Chinese immigrants have been continuously pouring into the United States with great numbers. As of today, Chinese immigrants alone have amassed as one-third of all new immigrants coming to the U.S.. Although they were successful in reaching the U.S., the Chinese immigrants’ first experiences and discrepancies among other immigrants as well as Americans were less so. In Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation, Min Zhou develops her thesis on the life of a Chinese immigrant, including communal lifestyle, occupation, and cultural assimilation. Throughout the book, Zhou also discusses the economic, political, and communal distinctions between Chinese immigrants versus other ethnic groups as well. Prior to 1965, the lives of Chinese immigrants differed from the 1960s to present day Chinese America. Because of this, Zhou is determined to acknowledge those differences and similarities to support her arguments about the ethnic enclave by “continuing to blend quantitative and qualitative methodologies...intending to focus on...issues of a comparative nature...and interethnic trajectories and a range of social contexts,” and hopefully spring further study towards this subject.1

Zhou begins her book by introducing some Chinese history, from the period of the Gold Rush all the way to the end of World War II. She also talks about demographic trends and some characteristics of contemporary Chinese America. According to Zhou, China was not known for its high emigration rate until late 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century. Before the Gold Rush, China dominated trade in its own region, also limiting its emigration. At its greatest economic point, China eventually acted aggressively towards its neighboring countries. This led to many wars later on that caused its own downfall, such as the two Opium Wars. In fact, the Opium Wars were major factors in China’s stray from “stability and prosperity to a century of defeat and humiliation”.2 As China proceeded to cast along its weak economy, Chinese immigration increased significantly after World War II. After the Second World War, tens of millions of Chinese immigrants emigrated throughout the world. Between 1949-1976, Chinese emigration was extremely strict. However, “rapid rising and highly publicized undocumented emigration [was] linked” to economic and structural reform in “China’s reconstructed political economy.”3 After concluding China’s more contemporary history, Zhou then begins to talk about the Chinese American community, originality, and social mobility. As said by Zhou, the Chinese American family’s development was affected by shortage of women as well as the “paper son” phenomenon (Chinese immigrant sons during 1940s, who were said to be sons of citizens but were sons on paper only), along with the “illegal entry of male laborers during the Exclusion Era.”4 However, these distortions were later fixed after the Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, presenting a more proportionate Chinese American community. Aside from the community, the Chinese immigrants themselves did not only come from the mainland but also the Chinese Diaspora (Hong Kong, Taiwan, etc.), which also implies that they come from different socioeconomic backgrounds. Among the different ethnic communities, the Chinese American community seemed to have a more objective basis towards social mobility. As stated, the Chinese American community was run by three “trajectories” for social mobility: hard work, ethnic entrepreneurship, and educational achievement.

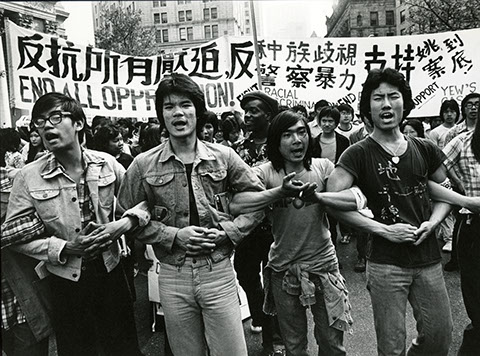

Zhou then emphasizes greatly on Chinese American community, especially New York City’s Chinatown, which was one of the most Chinese populated areas in the America. Later on in the 1980s, Flushing became a duplicate of Chinatown. These “chinatowns” were not only just for residential purposes; they meant job opportunities for new immigrants. Because of the increase of highly skilled and entrepreneurial Chinese immigrants coming into the U.S., Flushing’s economy began to develop in the late 20th century. Development of the enclave economy surely affected Chinese residents, “who found it important to live either in Chinatown or near the subway lines.”5 Chinatown’s enclave economy provided jobs for new immigrants and helped them accustom to a new lifestyle. Because many immigrants were not fluent in English, they preferred to live near other Chinese immigrants to form their own ethnic community. Following the creation of an ethnic community, resource-rich immigrants also created new modes of settlement; instead of residing in the central city, they began to migrate to white mid-class suburbia. In addition, the continuous flow of new immigrants marked a rejuvenation of a formerly inactive economy.

For a large portion of the book, Zhou discusses the organizational structure of the ethnic enclave. According to Zhou, certain ethnic groups have more entrepreneurship and are susceptible to self-employment as a way to gain socioeconomic mobility. To conceptualize immigrant entrepreneurship and the ethnic enclave, Zhou compares the middleman-minority entrepreneurs and the ethnic-enclave entrepreneurs. She also adds the differences between the ethnic economy and enclave economy. Aside from economics, Zhou includes the importance of Chinese media and the educational system. In the late 20th century, Chinese immigrants began to feel habituated in America; however, they still desired to connect with their homeland, making media imperative for connection with their origination. Although maintaining relations with their originality was important, what was more emphasized at the time was success. In the Chinese community, education was “valued...as the only road to success.”6 Not only was education valued to such an extent, it was also tied with the honor system within Chinese families. After 1965, Chinese immigrants were no longer uneducated peasants, but rather highly educated elite workers and entrepreneurs that pursued the American Dream.

Zhou concludes the last section of her book by discussing the Chinese family as well as future of Chinese America. History has shown that women were treated unequally compared to their male counterpart. This conceptualization has also been incorporated in the Chinese community. As the garment industry grew in the 1980s, female Chinese immigrants were inclined to take the job. In perspective of a Chinese family, the woman of the family was “expected to work in best interest of her family.”7 Though women were treated unequally, they held a strong part of the family as a whole just as the children did. Between the 1980s and 1990s, Chinese children began to show their abilities in academics, proving to outperform other ethnic groups. Since World War II, the Chinese Diaspora had opened up their educational system to both girls and working-class families. The emphasis on “educational attainment and the fierce competition for limited educational opportunities” produced extraordinary results.8 However, fear over political relations between Taiwan and China have forced many families to send their children to America, leading to the term “parachute kids.” The concept of parachute kids offers a unique prospect to show how pre-migration cultural values interrelate with structural opportunities. As more and more immigrants flee to America, Zhou questions the possibility of Chinese Americans becoming a “model minority” while simultaneously viewed as “perpetual foreigners,” leaving the future of the Chinese American community unknown.

Min Zhou’s purpose in writing Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation is to publicize the lifestyles and complications of a typical Chinese immigrant. Zhou emphasizes the differences between Chinese immigration before and after 1965. She writes this book as a way to educate the public about the Chinese community as well as further her research on ethnic enclaves, “[dispelling] the ‘model minority’...,[and] explore in greater depth global linkages between Chinese Diaspora.”9 Along with her own research, Zhou also applied the experiences of contemporary Chinese immigrants. To champion her statements about Chinese-American lifestyles, community, and sociality, Zhou provides statistics and sources from real immigrants. For the purpose of writing this book, Zhou intended to “focus on...other issues of a comparative nature-from a range of intra- and interethnic trajectories and a range of social contexts.”10

Min Zhou is a professor of sociology at UCLA and is the founding chair of the university’s Department of Asian American Studies. Through her various works such as Chinatown: The Socioeconomic Potential of an Urban Enclave and Growing Up American: How Vietnamese Children Adapt to Life in the United States, Zhou was able to develop the meaning of social capital to resources apprehended by not only individuals or groups, but also the processes of social interface leading to practical outcomes. Born in China, Zhou’s perspective and passion for the topic of Chinese America may have grown from her own experiences in this subject. Her sociological acumens have been chiefly within the fields of immigrant life and ethnic assimilation, especially attentive on the Asian American community. Being a Chinese American herself, Zhou may have favorable bias towards the Chinese community; however, the information that she provides is strictly factual.

During the time when this book was written, Chinese immigration had already been somewhat of a mainstream trend. Because of relations between China and Taiwan, as well as other countries that are included in the Chinese Diaspora, Asian families, especially the Chinese, believed it was necessary to migrate to the U.S. for better opportunity for jobs and new lifestyles. Because of China’s communist background, citizens’ perspectives changed towards their government, leading to their emigration. Though leaving their homeland, Chinese immigrants came to the U.S. with large amounts of financial capital, eventually helping America’s economy. These events may or may not had influenced Zhou’s purpose in writing Contemporary Chinese America; however, it definitely had an effect on the conclusions she made.

In Charlotte Brooks’ review of Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation, she lists the different concepts Zhou discusses in the book. Brooks then points out the diversity of Zhou’s writing, why “Chinese immigrants and their children have enjoyed tremendous economic and educational success in America in the last few decades.”11 Brooks also states Zhou’s rejections regarding cultural and structural arguments. Not only does this review strip the book down section by section but it also acknowledges Zhou’s case that “Chinese Americans-a group that because of the 1965 immigration law is today more than 60 percent foreign born-defy the old ‘assimilation cycle’ beloved of sociologists a generation or two ago.”12 Brooks praises Zhou for her persuasiveness but also criticizes her occasional derogatory statements that have been proven wrong and are disagreed by many readers. The reviewer also points out Zhou’s “unintentional echoes” about the model minority that Zhou herself punctures.13 Brooks then states that because of Zhou’s descriptions of Chinese immigrants before the 1965 immigration law, she sounds as though she is claiming that there is little to no change from then and now, which may cause controversy between critics. Brooks ends the review situating Zhou’s work as a valuable source for scholars that wish to study about the Asian American community and those who appreciate ethnicity, immigration, and modern America.

In Xiaojian Zhao’s review of the book, he recalls Zhou’s past books, saying that they are all related to the same overall subject: “economic, social, and cultural relations among Asian Americans.”14 The review praises Zhou’s contribution to the sociological field, allowing many scholars to quote her about ethnicity, immigration, and Asian American studies. Unlike Brooks, who noticed various flaws in Zhou’s writing, Zhao does not seem to discern any. Describing Zhou’s work as “passionate” and “effective”, Zhao eulogizes the author’s work about ethnicity and its effect on a highly assorted contemporary American society. Throughout the review, Zhao continuously extols Zhou’s advocating of themes and her ability to “combine original research with broad theoretical discussions.”15 Zhao ends the review stating that hopefully students and scholars would appreciate the importance of case studies as Zhou has shown in her works.

For those who wish to indulge in studies of Chinese American sociology, Zhou’s Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation is perfect for it. Throughout the book, Zhou explores Chinese history, immigration experiences, and community, proving to be a viable source of information about Chinese America. Readers can clearly see Zhou’s passion for this particular field of study. Although there may be bias and certain proclivities that may result in controversy, she does not fail to be factual when needed. This book does not only navigate Chinese occupation, lifestyle, and relations but also provides various sources that pertain to this subject. As both reviews have stated, Contemporary Chinese America offers so much for scholars as well as students who appreciate the Asian American society and are “passionate about research and [are] determined to make a meaningful contribution.”16 This book allows readers of different ethnic groups to relate to the experiences Chinese Americans had to deal with during and after the Exclusion Act and 1965 immigration laws. For Chinese Americans especially, this book should be appreciated for its dedication and honorability. Overall, Contemporary Chinese America by Min Zhou is definitely a book anyone who is intrigued by immigration, ethnicity, race, and contemporary Chinese America, should read.

The 70s was a period of economic crisis in America. However, Zhou’s perspective on this period of time is more concerned towards the Chinese community, not being able to migrate to the U.S. because of restrictions. In her arguments, the 1970s was a time of prosperity for both the Asian Community, mainly the Chinese, and the United States. Also in the early 1970s, China’s economy developed exponentially because of new reforms regarding agriculture, marketing, and industrialization. In the late 1970s, Chinese media took the role of “both an ethnic social institution and an economic enterprise facilitating immigrant adaption” as well.17 In the U.S. as well, “unprecedented Chinese immigration, accompanied by drastic economic marketization...and rapid economic growth in Asia... set off a tremendous influx of human capital and financial capital,” helping the American economy in its time of need.18 Zhou did not portray the 1960s and 1970s in any particular way. In terms of Chinese immigration and community, this period was a time of prosperity, specifically for the Asian community. In 1965, the Chinese immigration law was repealed, allowing an increasing amount of Chinese immigrants to enter the U.S.. From the 1960s to present day, immigration has only increased, leading to the assumption that Zhou portrayed the 1970s as a continuation of the 1960s.

This book’s entirety provides different views on the effect Chinese immigration had on the U.S. as well as how the Chinese community was affected by emigrating to the America. Until the end of the book, Zhou never gave up her admiration and pride for the Chinese community. In Zhou’s conclusion, the Chinese can never and will never be diminished as America becomes “increasingly multiethnic, and as ethnic communities and ethnic Americans become integral components of the society, the time will come...when the ethnic way is accepted as the American way.” 19

Footnotes:

- Zhou, Min. Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2009. 394

- Zhou, Xin. 473

- Zhou, Xin. 650

- Zhou, Xin. 707

- Zhou, Xin. 1030

- Zhou, Xin. 2238

- Zhou, Xin. 2577

- Zhou, Xin. 3032

- Zhou, Xin. 391

- Zhou, Xin. 402

- Brooks, Charlotte. “Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation.” Rev. of Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation. Journal of American Ethnic History 31.2 (2012): 148-50. Print.

- Brooks, Charlotte. “Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation.” Rev. of Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation. Journal of American Ethnic History 31.2 (2012): 148-50. Print.

- Brooks, Charlotte. “Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation.” Rev. of Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation. Journal of American Ethnic History 31.2 (2012): 148-50. Print.

- Zhao, Xiaojian. “Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation.” Rev. of Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation.Journal of Asian American Studies 13.2 (2010): 243-45. Print.

- Zhao, Xiaojian. 243-45. Print.

- Zhou, Min. Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2009. 405

- Zhou, Xin. 357

- Zhou, Xin. 798

- Zhou, Xin. 348

3 - 3

<

>