Vietnamese Immigratino

By Lannhi Nguyen

Sucheng Chan

Sucheng Chan was born in China and came to the United States at 16. After receiving a Ph.D. in political science from UC Berkley, Chan became a professor at UC Santa Cruz and later UC Santa Barbra, where she taught Asian American Studies. The self-taught historian is the author of nine published books.

After the Vietnam War ended, the people’s perspectives on the outcome of the war varied among both the Vietnamese and American populations. Some blamed U.S. foreign policy, while others claimed that the Vietnamese were abandoned. However, they all failed to realize that both the Americans and the Vietnamese were accountable for the aftermath. When Saigon “fell” on April 30, 1975, many Vietnamese fled to America in search of a safer home away from communism. The south did not only lose the war, but also their homes. This began the first of three Vietnamese immigration waves. In The Vietnamese American 1.5 Generation: Stories of War, Revolution, Flight, and New Beginnings by Sucheng Chan, Chan discusses the struggles of the refugees. Through a historical overview and several live accounts of refugees, Chan presents the history of Vietnam and the endeavors immigrants faced in hopes of helping both American and Vietnamese “be more tolerant of viewpoints other than their own”.1

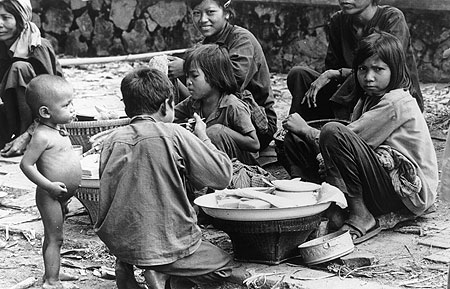

The First Indochina War (1946-1954) was a confrontation between France, which claimed Vietnam as a colony, and the communist Viet Minh. It ended with the Geneva Accords, signed in 1954, which divided Vietnam into the communist “North Vietnam” and the Republic of Vietnam, also known as “South Vietnam”. The agreement allowed a 300-day period which allowed people to move freely between the North and South before the border was sealed. The Second Indochina War (1954-1975), more commonly known as the Vietnam War, involved the Viet Cong led by Ho Chi Minh and the noncommunist south under Ngo Dinh Diem. America helped the South from 1965-1973. This war was both costly to the north and south as the “ground fighting and massive tonnage of bombs, napalm, and defoliants” displaced over 12 million people from each side.2 Because these displaced people had not crossed the international border, they were not yet considered refugees and could not be helped by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Instead, they were assisted by international relief organizations, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). These organizations would later play an active role in helping refugees resettle.

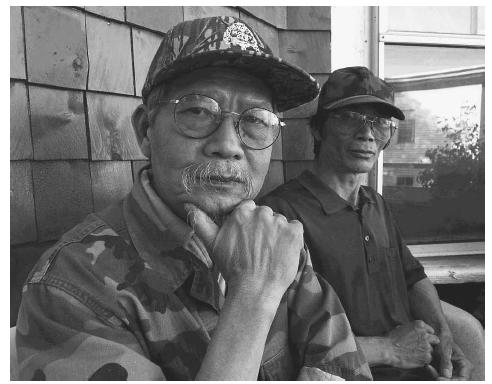

As the United States saw the “fall” of the South imminent, they began to prepare evacuation plans for both Americans and at-risk Vietnamese. On April 14, 1975, the attorney general gave the State Department permission to admit Vietnamese and Cambodian dependents. Other organizations such as the UNHCR and Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration (ICEM) helped locate countries that would admit the refugees. However, the exact number of refugees were unknown until last minute because Graham Martin, the U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, refused to release evacuation plans to prevent “widespread panic that might hasten the fall of the Thieu government.”3 When the collapse came closer, the State Department chose a random figure of one hundred and thirty thousand refugees: one hundred and twenty-five thousand Vietnamese and twenty-five thousand Cambodians. By the end of 1975, U.S. officials and voluntary agencies found sponsors for the refugees. October 31 was the deadline for moving refugees and the first wave of immigrants ended when the Interagency Task Force was disbanded on December 31. Camp Pendleton, located in California, was the first reception center for refugees. A total of three more reception centers were later added. The U.S. admitted a majority of the refugees as other countries “viewed the exodus as an American problem.”4 Only a few people escaped Vietnam by sea in the first two years after the war because the communist leaders sent many groups such as elected officials and police officers into “re-education” camps where they were subject to labor, abuse and malnourishment. Also, life after the war in the South did not change drastically because the two halves were not reunified immediately. The first wave mainly consisted of people who were in contact with the U.S. military and were targeted by communist forces. In the late 1970s, the second wave began which marked the beginning of the “boat people” exodus. The third wave was in the 1980s and 1990s.

April 1, 1975 marked the beginning of evacuation by fixed-wing aircraft. From April 22 to 30, the U.S. aircraft “lifted out about seventy-five hundred people a day” and the base was located at Saigon’s Tan Son Airport.5 However, the operation by fixed-winged planes ended quickly because on April 28, Northern pilots dropped bombs on the runway, which destroyed them. The International Control Commission negotiated with Communist forces “to allow the Americans a few hours to lift out, by helicopter, all the people still waiting at the airport.”6 Only the at-risk Vietnamese were allowed to leave. These people were those who were in contact with the U.S. government and their family members.

The “boat people” exodus was the largest contribution to movement of Vietnamese out of their country. Though the journey by boat was extremely dangerous and the chance of making it safely was as great as dying on the journey, many would still rather take the chance than suffer under the communist leaders. Many problems could occur on the journey such as getting lost in the vast sea, dying from hunger or thirst, or getting caught up in a storm. These people also risked running into pirates who would rape women, torture men, take the people’s belongings, and throw anyone who resisted off the boat. Though many believed a majority of immigrants arrived by plane, “about half of the people who fled Saigon were not evacuated by U.S. aircraft, as commonly assumed.”7 Vietnamese escaped from their home country because the communist would not allow rich people and the well-educated leave because they knew the communist leaders would make people suffer. Others, such as Catholics, left because they would be persecuted and would not be able to practice their religion. People usually either escaped by traveling on a cargo boat or a fishing boat, both of which were not made for sea travel. They ended up squeezing as many escapees as they could on the boat. Life on the boat was miserable as people would fight for space, portion the food supply, and use shoddy toilets. Because the toilets were a mere three pieces of wood that hung over the edge, some people would fall through the toilet hole and into the sea. Escaping into the boat was also a struggle in itself. Many were caught by the police and were thrown into jail with all their belongings confiscated. About half were caught by communist policemen before they even made it to their boats.

Chan believed that everyone should have a full understanding of the courage and endurance of the immigrants. Many families waited until after their husband, their father, or their brother left the “re-education” camps before they tried to escape. She hoped that people would be more tolerant of different standpoints. The inclusion of several different refugee accounts in Chan’s book helped display the similarities and differences between refugees and to show that no one individual’s outlook is representative of the Vietnamese perspective. Every refugee has their own story and each one is a unique account. The author wanted to show how the United States gave these people an opportunity even though they all struggled with the same language barrier at the beginning. In order for the refugees to “fit in”, she helped the immigrants learn that they did not have to abandon their culture or adopt every aspect of American culture, but had to “create culture and fashion identities that feel ‘true’ to who they are.”8

Born in Shanghai, China, Sucheng Chan herself also immigrated to the United States. With memories of the war in China, Chan is able to relate to the refugee families and hopes to have a more tolerable understanding of them. She presents the Asian-American studies in a new light as it reflects upon the Vietnamese Americans. Receiving a Ph.D. in political science, Chan was not a trained historian until she submerged herself in Asian American studies. Teaching Asian American Studies at UC Berkeley, Chan had her students write autobiographies to “deal with this clash of politics.”9 Because of the different views on the outcome of the war, the author wanted to show similar themes of immense loss, while also helping her students and other Asians to acquire skills that would allow them to help their homeland. Also after having written nine published books on several groups of Asian Americans, her study of Asian Americans is vast. Chan’s admiration for the immigrants is prevalent in her inclusion of the student narratives. Though Chan writes a typically unbiased viewpoint on the history by highlighting the different political viewpoints, the narratives of her students create a bias within themselves because they are different accounts of an experience.

Published in 2006, Chan collected and edited student narratives written in the late 80s and early 90s. She includes the student narratives to create a cultural historiography. However, she also begins this historical work with an overview of Vietnamese history to depict the complex history of Vietnam, as well as the intricacy of Asian-American studies. Because Chan was an antiwar activist and was “critical of U.S. foreign policy,” she shared the same perspectives of many Americans during the Vietnam war.10

In Vu H. Pham’s critical review of The Vietnamese American 1.5 Generation: Stories of War, Revolution, Flight, and New Beginnings, Chan’s view on Vietnamese American history is seen as valuable because she “acknowledges” that earlier attempts in representing “Vietnamese American perspectives did not receive much attention”.11 She reflects the past and current viewpoints of Vietnamese Americans who strongly hold anti-Communist views. The author remains unbiased even though her standpoint differs from these tensions. The student narratives, which were influenced by Chan’s teachings, were all analytical. The inclusion of these narratives as with experience as an Asian and as a Vietnamese American provides insight on two cultures as well as a “perspective reflecting [the students’] position as cultural brokers”.12 The author reflects upon the tensions between capitalism and communism, while presenting the Vietnamese American immigrants’ experiences at the same time. Because her work consists of a detailed history and narratives, she is able to present the history and different standpoints of the event all at once. According to Pham, Chan’s book is helpful for both teachers and students of Vietnamese Americans. Through the historical narratives, Chan is able to demonstrate the importance of Asian American studies.

The Vietnamese American 1.5 Generation: Stories of War, Revolution, Flight, and New Beginnings continuously addresses Vietnamese Americans while also focusing on the importance of the field of study of Asian American Studies. Her open views on the policies of the U.S. government or the Communist government reflects her hope for the tolerance of all views. Though she first states that she was critical of the Southern Vietnamese leaders and the U.S. foreign policy, Chan highlights the perspectives of others, such as the anti-communists or conservatives. She includes narratives of anti-Communists who claimed they left because they knew the truth of Communist leaders and that they made citizens suffer. The narratives provide an interesting and enjoyable reading experience. It was different from other historical books because of its focus on displaying the perspectives of many different viewpoints. Chan effectively creates a heterogeneous view on the history of Vietnam and its immigrants. A.W. Austin, another critique, acknowledged the historian’s key themes in the Vietnamese American experience and addresses the “in-between status of these newcomers and the importance of Asian American courses.”13 The work helped provide insight on Vietnamese refugees. Her inclusion of narratives helped make the sufferings far more personal because each person had a different experience, which allows the readers to envision the struggles of being an immigrant. Because the text was not overly detailed and contained enough information to generate an in-depth understanding of Vietnamese history, the reading was both insightful and interesting. It also helped shape an appreciation for the U.S. because through hard-work, each author was able to get past the language barrier and find success.

The 1970s was a time of chaos for both the Americans and the Vietnamese because as it was the time of both the continuation and end of a war. Though Americans withdrew its troops and signed a cease fire in 1973, the United States continued its involvement in Vietnam following the fall of Saigon as it helped refugees escape and resettle. This was a time of crisis for both countries because immigrants were quickly escaping their countries in hopes for a better life in America. By the spring of 1978, the United States received an average of fifteen hundred people a month and had to adopt ad hoc measures to deal with both land and boat people.14 Congress reacted to these great influx of numbers by passing the Public Law 95-412, which allowed unused space for boat people who reached Thailand. They also passed Public Law 95-145, which President Jimmy Carter signed in 1977. This allowed applicants to change their status from “parolee” to “permanent resident”.15 Boat people also attracted the attention of mass media, which helped reduce their wait time in first- asylum camps from several years to a few months. Conversely, the land people continued to wait several years before they were flown to resettlement camps. Congress passed the 1980 Refugee Act to deal with boat people- this was the first act passed that dealt specifically with refugees. Chan depicts that though the U.S. was in a time of crisis in dealing with the refugees, she was critical of their policies. She criticized the media for shaping the perceptions of citizens into helping the refugees unevenly and paying more attention on the boat people. The author also criticized the U.S. involvement in the war, mentioning the psychological defeat of Americans after the Tet Offensive and Nixon’s policy of Vietnamization, which led to the “inability of the United States to win the war.”16 The 70s was a continuation of the 60s as it was the continuation of American involvement in Vietnam. By including a historical overview, Chan combines the 60s and 70s together as a time of war and immigration.

Vietnamese immigration was a period of disorder and suffering. There were three waves of immigration as some either by land or sea. Many Viet Kieu, overseas Vietnamese, have developed a “deep hatred for Communism” which reflects the beliefs of many refugees.17 Chan, herself an immigrant, displays the endeavor of refugees and how war can deeply affect a person. While hoping to help Vietnamese Americans become tolerant of different political perspectives, she also presents the history of Vietnam and the stories of immigration.

Footnotes:

- Chan, Sucheng. The Vietnamese American 1.5 Generation: Stories of War, Revolution, Flight, and New Beginnings. Philadelphia, PA: Temple UP, 2006. Print. Preface ix

- Chan, Sucheng.55.

- Chan, Sucheng. 62.

- Chan, Sucheng. 65.

- Chan, Sucheng. 65.

- Chan, Sucheng. 143.

- Chan, Sucheng. 152.

- Chan, Sucheng. 252.

- Chan, Sucheng. Preface viii.

- Chan, Sucheng. Preface vii.

- Pham, Vu H. “The Vietnamese American 1.5 Generation: Stories of War, Revolution, Flight, and New Beginnings.” Journal of American Ethnic History (Fall 2007) Web. 30 May 2015.

- Pham, Vu. H.

- Austin, A.W. “The Vietnamese American 1.5 Generation: Stories of War, Revolution, Flight, and New Beginnings.” Choice Reviews Online 44.10 (2007): n. pag. Web. 30 May 2015.

- Chan, Sucheng. 68.

- Chan, Sucheng. 68.

- Chan, Sucheng. 53.

- Chan, Sucheng. 253.

4 - 4

<

>