A Liberal Court in an Era of Conservatism

By Leanna Hue

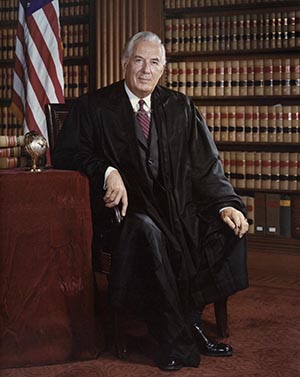

Earl Maltz

A distinguished professor at Rutgers University, Earl Maltz teaches Constitutional Law, Employment Discrimination, Conflicts of Law, and a seminar on the Supreme Court. Maltz has also published three books: Rethinking Constitutional Law: Originalism, Interventionism, and the Politics of Judicial Review; Civil Rights, The Constitution and Congress; and The Chief Justiceship of Warren Burger.

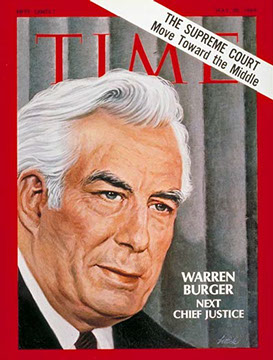

The 1970s were a tumultuous time for the Supreme Court of the United States. Not only did Nixon’s Watergate scandal and issues, such as abortion and affirmative action, create a divided America, but also the Supreme Court justices were disordered and chaotic due to conflicting opinions within the Court itself. This turmoil characterized the struggle of Chief Justice Warren Burger as he attempted to unite the opinions of other justices. Although Burger was a conservative, Earl Maltz, in his book The Chief Justiceship of Warren Burger, 1969-1986, “advances the controversial thesis that Burger Court activism occurred almost entirely in a liberal political direction.”1 Maltz analyzes the Court’s approach to various issues, such as judicial restraint, economic regulations, and federalism, through his explanation of instrumental cases and decisions to support this point.

Maltz begins his book by explaining his opinions about the Burger Court and expressing the difficulties of characterizing the Court as a whole. He argues that “the Burger Court’s jurisprudence lacked any discernible focus…the Court was composed of nine independent contractors with widely differing political and jurisprudential agendas.”2 To provide the reader with some background, he describes the life stories of Chief Justice Warren Burger as well as the other justices on the Burger Court. He addresses the idea of judicial restraint, a major theme in the Burger era. Although the previous Supreme Court, under Earl Warren, advocated pro-liberal reforms, the Burger Court “professed to favor a renewed commitment to the idea of judicial restraint,” the ability of the Supreme Court to restrict the actions of the other branches of government.3 In the United States v. Nixon decision, which involved the famous Watergate scandal, the Court asserted its powers by upholding the conviction that the Supreme Court had the final voice in answering constitutional questions, and no one, not even the President, would be above the law. Another prominent issue during the Burger era was the strained relationship between the powers of the federal and state governments. After many debates and court cases, the Court decided that “the Constitution provided sufficient structural protections for state sovereignty…it had proved impossible to devise a principled line that divided permissible federal regulations of the states from unconstitutional intrusions on state autonomy.”4 Although the Burger Court was divided on the issues of judicial restraint and states’ rights, it was able to compromise and come to a consensus on these two key issues.

Other issues that challenged the Burger Court were economic regulation and freedom of speech. Maltz argues that two issues of economic regulation plagued the Burger Court: interpretations of federal regulatory statutes and constitutionality issues, especially concerning labor unions versus corporate management. Generally, the Court tended to show disdain towards labor unions and loosened restrictions on antitrust laws. The justices were willing to “constitutionalize” economic rights; however, they expressed “a commitment to the concept of judicial deference and concerns for states’ rights.”5 Still, Maltz argues that although most of the Court’s decisions were theoretical, the justices established essential practical limits on federal government authority to regulate economic interests. As for freedom of speech, the Burger Court, taking the strength of a state’s interest into consideration, successfully introduced significant development in the regulation of sexually explicit materials in places such as theaters and radio stations. Instead of restricting commercial speech, the Court protected consumers affected by damaging, inaccurate commercial speech. In these two cases, Maltz emphasizes the victory of the liberals in securing the rights of the people.

In continuing to support his position that the Court leaned to the left, Maltz then proceeds to discuss important low-profile cases, concerning both the “lawyer’s law” and the administrative state, before he introduces major, controversial issues. In the case of “lawyer’s law,” which dictated how civil law suits were conducted, the Court deemed the federal law should govern civil disputes about citizenship diversity. However, its decisions involving personal jurisdiction were almost random. The Burger Court abandoned traditional values (precedents) to provide citizens greater defenses against the abuses of the administrative state. To accomplish this, the Court “expanded the scope of the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments as substantial constraints on administrative action.”6 Between administrative agencies and Congress, however, the Burger justices refused to give Congress additional control over these agencies and reduced the judicial functions in these disputes. Not only did challengers to administrative actions try to maximize their rights and protection, but criminal defendants tried also. Concerning the rights of criminal defendants, the Court found all standing laws on the death penalty unconstitutional in 1972 but reinstated the death penalty in 1976 under narrowly-defined circumstances. However, the Court’s criminal procedure rulings showed the more conservative side of the Burger Court, as it restricted the exclusionary rule, which allowed either side in a criminal proceeding the right to remove evidence. Focusing on the Free Exercise Clause and Establishment Clause, which people challenged due to its relationship between church and state, the Burger Court initially advocated the liberals’ stringent separatist belief that church and state should have complete separation. However, due to the end of the Burger era, the Court began to accept any relationship between church and state. Although the Court expanded the rights and protections of citizens in a more liberal sense, it also showed its conservative colors when dealing with criminal procedure and religious clauses in the Constitution and related statutes.

Finally, Maltz ends the book with the most controversial issues of the Burger Court: race, nonracial classifications, and abortion and privacy. Again revealing its liberal sentiments, the Burger Court found overt racial discrimination intolerable and “emphatically rejected even a slight delay in the implementation of a desegregation order.”7 Because race was a suspect classification, all racial classification was subject to strict scrutiny by the courts. Racial classification was especially important and controversial in the idea of affirmative action, in particular the landmark case Regents of University of California v. Bakke, in which the Court ruled that universities could use race as a factor in admissions, as long as it is considered alongside other factors, to increase educational diversity. Maltz transitions into cases involving nonracial classifications—categorization based on sex, age, mental state, and physical state, for example. While Congress passed laws protecting the developmentally disabled and the elderly, the Supreme Court dealt with sex discrimination, which it found intolerable. Because the Court opposed sex discrimination and supported feminism, this issue became a victory for the liberals for the most part, leading to the disputed issue of abortion. The symbol of the Burger era and a milestone in the issue of abortion, Roe v. Wade limited the government’s power to regulate abortion. The case raised the question of when and if a fetus should be considered a person; however, the Court’s decision reflected pro-choice viewpoints, arguing that the right to choose to have an abortion is equivalent to the right to privacy, and that restriction of this right is only allowed if the government has a compelling interest. Nevertheless, both the government and the American population remained divided on this issue. Because the Court supported the rights of the individual in the issues of race, nonracial classifications, and abortion and privacy, Maltz argues the Court takes a leftist approach in these issues.

Even though most commentators argue that the Burger Court was either generally conservative or centrist, Earl Maltz takes the unique stance that the Court was “far from being a conservative or centrist institution…on constitutional issues the Burger Court can plausibly be seen as having produced the most liberal jurisprudence in history.”8 Many justices on Burger Court were appointed by Republican presidents; however, the Court’s liberal nature is apparent through the disregard to previously widely held American moral values and judicial precedents and the implementation of new ideas. For example, before Roe v. Wade, challenging abortion regulation faced overwhelming obstacles, and all fifty states either had prohibited abortion or permitted it in narrow circumstances. In the Roe decision, the Court took the widely challenged pro-choice view and invalidated the laws limiting or prohibiting abortion. Because it produced many novel decisions, Maltz argues that the Burger era “created dramatic new liberal constitutional doctrine” and reflected a shift in American liberalism.9

Well-informed about law, Earl Maltz is a distinguished professor at Rutgers University, teaching Constitutional Law, Conflicts of Law, and a seminar on the Supreme Court. Before writing The Chief Justiceship of Warren Burger, Maltz wrote about the Burger Court’s approach to specific topics—gender-based discrimination, the Commerce Clause, interstate commerce, and “alienage” classifications. Due to Maltz’s interest and expertise concerning the Burger Court and the Supreme Court in general, Herbert A. Johnson chose Maltz to write The Chief Justiceship of Warren Burger, a compilation of the political issues from his previous works, as an addition to his series Chief Justiceships of the United States Supreme Court. As a writer of many works concerning individual rights and the issues discussed in The Chief Justiceship of Warren Burger, Maltz must have realized how instrumental the Burger Court was in contributing to forward individual rights and protections and how it reflected the shift towards liberal beliefs, which influenced Maltz’s decision to advocate the seldom-held belief that the Burger Court was in fact liberal. When writing the Warren Burger book in the 1990s, Maltz took a new look at certain key issues of the Burger era as he observed an extension of these themes two decades later. For example, “in 1992, the Supreme Court revisited the Roe v. Wade decision when it took up Planned Parenthood v. Casey” as well as many other lawsuits.10 Seeing the effect of Roe allowed Maltz and the rest of America to realize its full impact and, as a historian, Maltz was prompted to revisit the Burger era. Between his renewed interest in the Burger Court due to recent abortion cases and an invitation to write a book for a Supreme Court Chief Justice series, Earl Maltz was motivated to write a comprehensive work on the Burger era.

In his critique of The Chief Justiceship of Warren Burger, 1969-1986, David Yalof, a professor from the University of Connecticut, praises Maltz in his summary of the Burger era but chides him for his lack of analysis of the era. Although Yalof is impressed by the amount and breadth of the work, he is not impressed by the absence of the answers to controversial questions. Recognizing the difficulties of characterizing Chief Justice Warren Burger, Yalof believes “Maltz’s book would seem to represent a golden opportunity for a balanced consideration.”11 However, he claims Maltz does not address the nature of the era; Maltz has a sophisticated analysis of the Court’s opinions but not of the Court and the justices on it. In addition, Yalof chastises Maltz’s use of biased and limited secondary sources to obtain information for important cases. As a result, Maltz does not present any new insights about the Court or the psychology behind its actions. Yalof claims that Maltz’s book, published in 2000 (fourteen years after the end of the Burger era), does not relate the Burger Court decisions to the present day in order to access its legacy, “denying the reader any type of hindsight perspective.”12

On the other hand, Howard Ball has only praise for Maltz and his book The Chief Justiceship of Warren Burger, 1969-1986 in his critical review. He believes Maltz argues successfully that prior to the Burger era, “Supreme Court decisions by and large reflect, first, the predilections of the presidents who appointed them and, second, the change of values in the larger society.”13 Maltz depicts a clear contrast between those Supreme Court decisions and the decisions of the Burger Court, who, although all appointed by Republican presidents, in many ways abandoned the conservative ideology. However, Maltz makes it apparent that, like their predecessors, the members of Burger Court reflected society’s shifting opinions. Ball extols Maltz’s careful examination of the decisions made by the Burger Court and calls the book an “excellent study” of the jurists.14

Although Maltz is commendable for his thorough research and extensive review of the Burger era, he offers a mere summary of the cases and fails to provide the overall picture of the era. Thirteen out of the fourteen chapters are structured with introduction of an issue that plagued the Burger Court, explanations of court cases concerning that issue, and most of the time, a one- or two-paragraph conclusion. The court case descriptions are cycles of a paragraph describing a case and the opinions of every justice on that case for every case, but Maltz is unclear about what the final decisions are and what effects they have on society. For example, after describing the case Regents v. Roth, Maltz writes the opinions of the Court: “Speaking for himself, the chief justice, and Justices White, Blackmun, and Rehnquist, Justice Stewart concluded... [and] By contrast, in dissent, Justice Douglas contended…[and] Justice Marshall went even further, arguing…”15 This repetitive cycle creates for a dry read as the bulk of the book is written in this manner. In the concluding paragraphs, Maltz only states that the justices were divided on the issue and whether he believes the Court took a conservative or liberal approach. Like Yalof says in his review, Maltz fails to provide a connection to the future and an indication of the true legacy of the Burger Court.

Because Maltz focuses mostly on the court cases during Burger era, he incorporates little information about this troublesome time period (1969-1986) itself. The era was strife-ridden due to Roe v. Wade and the Watergate scandal. Beneath these two emotionally-charged national issues was a court with sharply divided ideologies. Instead of addressing whether the 1970s were a time of happiness and success or a time of hardship and crisis, Maltz discusses the successes and failures of Warren Burger as a Chief Justice but not the Burger Court as a whole. Commending Burger for his administrative success, Maltz comments, “Burger did much to improve the physical conditions under which the justices worked… [but] his administrative contributions went well beyond a simple concern for the proper operation of the Supreme Court itself.”16 On the other hand, as a conservative, Burger was not able to implement the judicial reform that he favored since he “lacked the mental capacity and rhetorical skill to adequately elaborate and defend an alternative approach to Warren Court activism.”17 Still, Maltz relents in explaining that the Burger’s failures were not entirely his fault and that his inadequacy was also due to the highly diverse Court. As a result, the Court was divided on most issues, and no rigid point of view could produce consistent majorities in decisions. Overall, Maltz argues that Burger was a satisfactory Chief Justice who, although strong in some points, possessed inadequacies that prevented him from winning battles on his own.

Although Maltz did not mention the welfare of the United States itself during the Burger era, he did make connections between the Burger Court (1969-1986) to its predecessor the Warren Court (1953-1969). The Warren Court was an established liberal group of justices, and Maltz argues that the Burger Court paralleled the vision of the previous Court. As a result, the Burger justices tended to protect the Warren Court “revolution.” However, in “the Burger Court decisions that created dramatic new liberal constitutional doctrine in cases dealing with the death penalty, abortion and women’s rights generally, protection for illegitimates, commercial speech, and aid to parochial schools,” the justices either modified or abandoned Warren Court precedents.18 In this manner, Maltz argues that the Burger Court was a continuation of the Warren Court, as it not only maintained Warren Court ideas but also pushed society further in the liberal direction.

To prove the liberal nature of the Burger Court, Earl Maltz provides a broad look at the era of the Supreme Court from 1969 to 1986, as he describes a wide variety of cases and issues. In doing so, Maltz accomplished the complicated task of capturing “an explosion of doctrinal developments whose magnitude surpassed even that of the regime of [Burger’s] predecessor, Earl Warren.”19 Today, Americans live in the liberal legacy of the Burger Court through its actions concerning abortion, political corruption, and racial integration.

Footnotes:

- Maltz, Earl. The Chief Justiceship of Warren Burger, 1969-1986. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000. xii.

- Maltz, Earl. 3.

- Maltz, Earl. 32.

- Maltz, Earl. 66-67.

- Maltz, Earl. 91.

- Maltz, Earl. 143.

- Maltz, Earl. 177.

- Maltz, Earl. 1.

- Maltz, Earl. 266.

- Fleischer, Victoria. “Roe v. Wade’s Influence Felt on 1992 Abortion Case.” PBS. PBS, 22 Jan. 2013. Web. 30 May 2015. <http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/1992-decision-was-seminal-abortion-case-in-post-roe-v-wade-america/>.

- Yalof, David. “Earl M. Maltz. The Chief Justiceship of Warren Burger, 1969-1986.” The American Historical Review 107.1 (2002): 250. JSTOR. Oxford University Press. Web. 20 May 2015. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/532206>.

- Yalof, David. 251.

- Ball, Howard. “The Chief Justiceship of Warren Burger, 1969-1986 by Earl M. Maltz.” The Journal of American History 88.2 (2001): 739. JSTOR. Organization of American Historians. Web. 20 May 2015. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/2675251>.

- Ball, Howard. 740.

- Maltz, Earl. The Chief Justiceship of Warren Burger, 1969-1986. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000. 145.

- Maltz, Earl. 10.

- Maltz, Earl. 11-12.

- Maltz, Earl. 266.

- Maltz, Earl. xv.

4 - 4

<

>