The Week that Changed the World

By Michael Ly

Chris Tudda

Chris Tudda has been a historian since 2003. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and Government, and a Doctor of Philosophy in American History. Currently, he teaches U.S. foreign policy history, specifically that after World War II, in The George Washington University and Columbian College of Arts & Sciences.

Following the end of World War II and amidst the hostility of the Cold War, the United States in the 70s was lost in a state of incredible international power with the duty of preserving both itself and the world. Elected at the eve of the new decade, President Nixon was adamant on establishing normalized foreign relations. However, contrary to his predecessors, he recognized the possibility of an enemy greater than the Soviet Union. Even before Nixon’s presidency was his realization that “China had some 700 million people and was inevitably an important factor in the world,” and that the Cold War would be frozen in place “until the China issue was resolved.”1 In Chris Tudda’s A Cold War Turning Point, Nixon’s trek into China’s isolationist disposition is thoroughly analyzed using recently released documentary evidence from U.S. and international archives and, for the first time in rapprochement historiography, extensive use of the White House tapes. By using these tapes, Tudda is able to provide a new dimension of scrutiny through transcriptions showing that “Nixon and his advisors engaged in thoughtful, often brilliant discussions about the geopolitics and the intentions and capabilities of their allies and adversaries.”2 With the power of retrospect, the resulting book is at its core an attempt to analyze the extent to which the Nixon administration succeeded in improving U.S. international image during a time of increasingly controversial international tension.

Tudda begins by putting into perspective the state of the Nixon administration at the beginning of Chinese rapprochement consideration. Upon his election, Nixon announced the beginning of “an era of negotiation” in which the United States “[extended] the hand of friendship to all people, to the Russian people, to the Chinese people, to all the people in the world.”3 In addition to international affairs, Tudda also delves into domestic and internal disputes in the administration itself. Introduced early on and revisited many times is the rivalry between Secretary of State William P. Rogers and presidential adviser Dr. Henry A. Kissinger. Although the two harbored conflicting ideals over foreign affairs, they were both considerable factors in Chinese rapprochement. Luckily, China’s situation promptly revealed a slight margin for error — Nixon’s push for international normalization was conveniently aligned with Sino-Soviet border fights, which convinced Mao Zedong to explore rapprochement with the Nixon administration because it seemed as if “the Soviet Union had replaced the United States as China’s principal enemy.”4 Whether or not Nixon was aware of this reciprocity and despite the natural outward cynicism of China regarding rapprochement with its supposed enemy nation, the Chinese martials thought of Nixon as “unlike other presidents” in his view of China as a “potential threat” rather than a “real threat.”5 Through attempts to communicate with China through Warsaw and Pakistani channels, Tudda notes the administration’s extremely slow but steady progress in rapprochement. In the tentative initial communication with Chinese officials, Washington realized the significance of Beijing’s sensitivity over Taiwan and the obstacle that it posed to the reconciliation between the two nations. In 1970, Mao finally decided to push for rapprochement himself, although indirectly, by inviting American journalist Edgar Snow to “join him at Tiananmen Square to observe the parade in honor of China’s National Day.”6

After reviewing the fundamental building blocks of the Sino-U.S. relationship, Tudda dedicates a large portion of his book to analyzing Kissinger’s two visits to Beijing, which, although executed secretly, served a great purpose in relaxing Chinese apprehensions. Thanks to favorable Pakistani relationships with both the United States and China, the three nations were able to work out a scenario in which Kissinger could travel to China incognito in 1971. In the seven-hour meeting with first premier Zhou Enlai, Kissinger was able to present his thesis on behalf of the Nixon administration on “why the United States wanted rapprochement and how the administration looked forward to the talks and the responsibilities that went along with it.”7 Tudda mentions multiple times the friendly environment of the meetings, and its serving as an example of “exchange where each country recognizes each other as equals.”8 Inevitably, the subject would change to the future of Taiwan, which was especially important to Zhou. Although Kissinger attempted to avoid these negotiations for lack of a certainty, Zhou’s persistence prompted him to admit that the evolution of U.S. politics was “likely to shift in the direction of the People’s Republic of China,” which Zhou deemed as “hopeful.”9 It was at this meeting that plans for Nixon’s personal visit to Beijing were introduced. Following Kissinger’s initial visit, a second, public trip was taken as a “dress rehearsal” to Nixon’s Beijing summit. Still, despite its premeditated and almost scripted nature, Tudda emphasizes the importance of this second trip as an opportunity to deepen the Kissinger-Zhou relationship and to “gradually introduce the American way of diplomacy” to “the lower levels of Chinese leadership.”10 The addition of China and expulsion of Taiwan from the United Nations is seen by Tudda as a failure of Nixon and Kissinger’s “realist” foreign policy in face of “the public reality that could not have things both ways.”11 In order to win China, the United States would have to sacrifice Taiwan.

In the time period between Kissinger’s second China trip and Nixon’s Beijing summit, Tudda focuses on U.S. non-Chinese international relationships, namely those which were involved in the Indo-Pakistani crisis. Initially, the United States had thought that opening up to China would remind Moscow that “it cannot speak for all Communist countries” and that improvement in Sino-U.S. relations would force Moscow to be “more cooperative in many issues.”11 On August 9, 1971, however, India signed a Friendship Treaty with the Soviet Union, a move that angered both the United States and China. Tudda remarks that Nixon’s angry reaction to this treaty was rather ironic considering the administration’s recent activity with China. He states that “here the supposed realist who played his own geopolitical games either could not understand, or respect, India’s decision to move closer to the Moscow in order to strengthen its own national security.”12 The administration, however, initially believed that China would move in to protect Pakistan as the newest member of the United Nations, only to be disappointed by China’s lack of action. During the crisis, the antipathy between Kissinger and Rogers was further evidenced. While Kissinger suggested that the United States take steps to internationalize the crisis to scare the Indians from attacking Pakistan, Rogers pushed for a pure diplomatic solution as he doubted U.S. ability to handle the situation. Nixon sided with Rogers’ assessment. Tudda explains that, despite U.S. fears of the Indo-Pakistani crisis, in reality the administration could do little to change the conditions on the ground in South Asia, and therefore relied on the incorrect assumption that the more influential China would intervene themselves. In essence, the crisis was an example of U.S. misinterpretation of Chinese nature. According to Tudda, “the Nixon administration misread Chinese assumptions and mistakenly looked at the crisis in South Asia from a geopolitical standpoint.”13

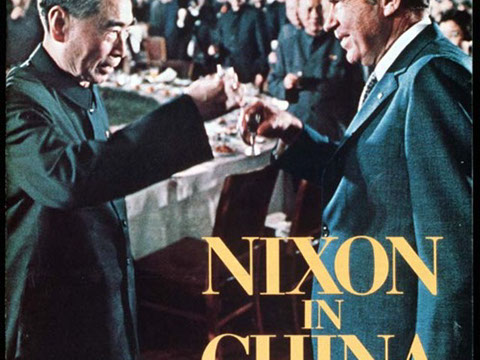

Tudda’s studies accumulate in Nixon’s Beijing summit in 1972 and his analysis on the significance of the week-long visit. Up to this point, the administration had learned a great deal about the Chinese through their political interactions. Going into the summit, Nixon realized that “the Chinese had no use for ‘tactical details’ but instead acted in their long-term interests” as demonstrated in the Indo-Pakistani crisis.14 Kissinger recapitulated the situation by saying that “the Chinese are both fanatic and pragmatic...their ideology was diametrically the opposite of the United States, yet they were ‘hard realists’ who understood that they ‘need us’ because of the Soviet, Japanese, and Taiwanese threats.”15 On Mao, Kissinger observed that “there was no point in seeking to deceive the specialist in the foibles and duplicity of man...I have met no one who so distilled raw, concentrated willpower.”16 Contrary to Kissinger’s initial impression of Mao, Tudda explains the summit’s purpose in officially opening up Sino-U.S. relations and establishing a foundation in which the two nations could find common ground. During a four-hour discussion with Zhou, Nixon was able to establish his Taiwan policy with the first premier, assuring him that Taiwan was a part of the greater continental China. In another four-hour meeting, the two discussed situations in India, Pakistan, Korea, Japan, and Soviet Russia. In a toast that closed “the week that changed the world,” Nixon commented on the success of the Beijing summit, stating that “the two nations, despite their very real differences, could build a new world, a world of peace, a world of justice, a world of independence for all nations.”17 Tudda agrees with Nixon’s assessment, labeling the summit as “an important turning point in the cold war.”18 Communist China now enjoyed the international legitimacy that it had craved, and the Soviet Union was forced to reassess its international actions. Nixon’s persistence began a cautious process that slowly achieved normalization over the next six years.

In writing this book, Tudda hopes to convey the importance of Sino-U.S. rapprochement, and how it “fundamentally altered the dynamics of the cold war.”19 This rapprochement, however, was only possible because of the conditions present during the Nixon administration. Because of Nixon’s willingness to stray from the anti-Chinese mindset practiced by his predecessors, the United States was able to achieve an international normalization that had paramount significance on its Cold War against the Soviet Union. For example, Tudda remarks that Nixon was “unlike Johnson” in that he “refused to let the Vietnam War get in the way of rapprochement,” and instead “compartmentalized Vietnam and China policies.”20 Throughout this work, he emphasizes the importance of Nixon’s openness numerous times, asserting that his “gradual easing of trade and travel restrictions led Mao to respond in kind, albeit slowly, by releasing political and other prisoners, inviting the U.S. ping-pong team to Beijing, and, of course, arranging for Kissinger’s secret trip and the summit.”21 Using analyses of both public political policies and personal conversations between Nixon, his advisers, and foreign officials, Tudda stresses Nixon’s patience and persistence in pursuing rapprochement, despite multiple international obstacles that made the road to normalization a long and winding one. However, he also comments on the shortcomings of the rapprochement process, namely Nixon’s “refusal to stop the Kissinger-Rogers rivalry,” which “hampered the creation of a coherent policy.”22 Although the administration ultimately succeeded in their excursion into China, Tudda concedes that domestic rivalry was one of many hidden problems that threatened its attempt.

Tudda has been a historian in the Declassification and Publishing Division of the Office of the Historian, Department of State, since 2003. He is also the author of The Truth Is Our Weapon: The Rhetorical Diplomacy of Dwight D. Eisenhower and John Foster Dulles. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and Government, and a Doctor of Philosophy in American History. Currently, he teaches U.S. foreign policy history, specifically that after World War 2, in The George Washington University and Columbian College of Arts & Sciences. Tudda’s credentials would qualify him as an expert on Sino-U.S. relations, making it only natural for him to eventually write a book on the subject. His position in the Department of State may have led him to lean toward Kissinger’s policies when explaining the Kissinger-Rogers rivalry, although his bias is hard to notice if at all existent. As a government historian and professor, Tudda is more inclined to maintain a sense of professional objectivity when assessing the rapprochement process, which is apparent through his ability to find successes and failures in all parties discussed. Instead of excessively covering Nixon’s success, Tudda remembers to note Mao’s crucial and unexpected reciprocity in making “the most important move inviting Nixon to visit.”23 This objectivity is the result of the significant change in general attitude within the United States since the time of the Cold War. Writing this book in 2012, Tudda enjoys not only the most recent intelligence regarding previous Sino-U.S. relations but also the option of writing a book that celebrates not only the brilliance of Nixon but also that of Mao and Zhou. By providing an analysis in retrospect rather than in the heat of the moment, he is able to provide an honest and accurate account of a previously sensitive subject.

In a review by Chinese lawyer, author, and Cornell graduate Gordon G. Chang, Tudda’s book is commended for its clearing up of misconceptions surrounding rapprochement. Chang notices that the “backdoor diplomacy” detailed by Tudda both “restores some balance” to the “Kissinger-centric understanding” and “debunks” the “triangular diplomacy” assumptions that had previously surrounded the process.24 All of this, Chang says, was made possible by Tudda’s extensive scrutiny of the most recently released documents and untouched White House tapes used to give readers an insight on the internal discussion of the White House during Nixon’s administration. By using tapes, Tudda is able to “shed new light on this much-analyzed series of events, especially those in the three years leading to ‘the week that changed the world’”25

In a review by Austin Peay State University professor, University of Houston graduate and diplomatic military historian Dr. Christos G. Frentzos, Tudda’s usage of White House tapes is again applauded. Frentzos notices Tudda’s equilibrium in “praising Nixon’s foreign policy realism” while “[recounting] the administration’s shortcomings” with an objectivity that would bring justice to both.26 Frentzos’ main captivation with Tudda’s “fine work” seems to lie fully in the thoroughness yet equality of his commentary, two traits that he believes is essential to writing an informative study.27

At its core, A Cold War Turning Point succeeds in defining the rapprochement process as one of imperfect yet effective persistence and reciprocity between the United States and China. With newly released documentary evidence and White House tapes, Tudda opens the reader to a new dimension of analysis that explores personal conversations within the Nixon administration. Tudda states that “an important component of Sino-U.S. rapprochement that continues to cause controversy involves the role of secrecy in foreign policymaking.”28 By skillfully weaving quotations from the influential leaders of the time into his explanation of the rapprochement process, Tudda is able to parlay internal discussion into international politics and explain their principal importance in interfering with yet ultimately achieving the Beijing summit. He analyzes the role of secrecy in “overcoming significant domestic opposition” as well as its “backfire on the United States and Pakistan” in order to provide the reader with a more concrete understanding of the U.S. mindset during a time of chaos.29 In essence, Tudda is able to use the entirety of resources available to him to create an unprecedented insight to the true intentions of the administration and their implications on the entire world and present Nixon and his advisers as ordinary humans with a far reaching dream.

Tudda believes that the 70s was a time of crisis not only in the United States but throughout the entire world. Nixon’s decision to push for rapprochement was “a long and winding” process “that only took a few years,” but resulted in “shifting perceptions and conceptions of national security” as seen in “sources from American, Chinese, European, and Soviet archives.”30 Because of domestic opposition, much of the rapprochement process was carried out in secret, which serves as a testament to U.S. instability and controversy during this time. However, Tudda does support the notion that the United States changed its political agenda from that of the 60s, most significantly because of Nixon’s change in China policy, and remarks that “Nixon’s determination to repair the Sino-U.S. relationship had marked a clear change from his four predecessors.”31 Although Cold War politics continued to dominate foreign affairs as before, the actions of Nixon served as an example of normalization and a cry for peace between an international and potential superpower that was unprecedented in the time period.

Ultimately, A Cold War Turning Point analyzes not only what Reagan deemed “one of the greatest weeks of the American presidency” but also the conditions and relationships that played a significant role on the summit years before it was even considered.32 In writing this book, Tudda connects one of the most significant political moves in international history to its most fundamental participants, giving readers an exclusive look into all aspects of the “week that changed the world.”

Footnotes:

- Tudda, Chris. A Cold War Turning Point: Nixon and China, 1969-1972. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 2012. Print. 1

- Tudda, Chris. ix

- Tudda, Chris. 2

- Tudda, Chris. 13

- Tudda, Chris. 23

- Tudda, Chris. 59

- Tudda, Chris. 89

- Tudda,Chris. 90

- Tudda, Chris. 91

- Tudda, Chris. 126

- Tudda, Chris. 125

- Tudda, Chris. 145

- Tudda, Chris. 166

- Tudda, Chris. 178

- Tudda, Chris. 181

- Tudda, Chris. 183

- Tudda, Chris. 201

- Tudda, Chris. 203

- Tudda, Chris. 210

- Tudda, Chris. 206

- Tudda, Chris. 205

- Tudda, Chris. 208

- Tudda, Chris. 191

- Chang, Gordon G. “A Cold War Turning Point: Nixon and China, 1969-1972 by Chris Tudda.” Journal of Cold War Studies 16.3 (2014): 218-19. Web.

- Chang, Gordon G. “A Cold War Turning Point: Nixon and China, 1969-1972 by Chris Tudda.” Journal of Cold War Studies 16.3 (2014): 218-19. Web.

- Frentzos, Christos G. “Reviews: A Cold War Turning Point :.” Reviews: A Cold War Turning Point :. American Library Association, n.d. Web. 31 May 2015.

- Frentzos, Christos G. “Reviews: A Cold War Turning Point :.” Reviews: A Cold War Turning Point :. American Library Association, n.d. Web. 31 May 2015.Review

- Tudda, Chris. 208

- Tudda, Chris. 208

- Tudda, Chris. 203

- Tudda, Chris. 205

- Tudda, Chris. 202

3 - 3

<

>