Progression of Radical Feminism

By Shruti Karnani

Alice Echols

Alice Echols is a Professor of History at the University of Southern California. She has a B.A. in History from Macalester College and a M.A. and Ph.D. in History from the University of Michigan. Her other work includes Scars of Sweet Paradise and Shaky Ground.

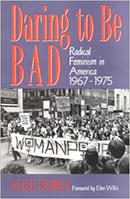

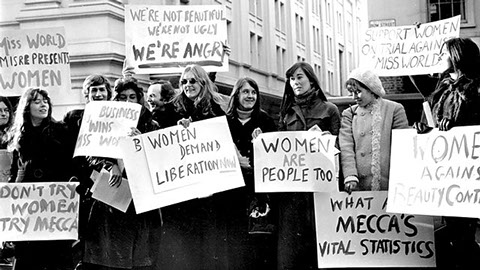

America in the 1970s witnessed a new social movement that arose to challenge masculine supremacy and reject social norms of the decade. The second feminist movement ultimately transformed society’s way of thinking about gender and brought about many institutional and legal changes. Radical feminism is defined by the rejection of patriarchy and incorporated in the larger second wave feminist movement which broadened the debate to a wide variety of issues including abortion, sexuality, and marital rape. Historian and Professor Alice Echols, in her work Daring to be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967-1975 stresses the differences between the several women’s movement organizations that sprung up during this era. Her presentation of research on feminist organizations, including strong historical examples and important quotes from leading feminists, builds the basis of the differences between these radical groups. Although not a united movement, these separate and younger generational organizations were the source of influential and innovative techniques. She documents the growth, infighting, and eventual decline of the younger branch of radical feminism though the description of social and intellectual history during the 1970s. Alice Echols also introduces her readers to several radical organizations, emphasizes the accomplishments of each group, and provides a brief introduction to their foundational view.

Daring to be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967-1975 opens with an introduction to chronicle the overall progression of the women’s right movement during the era. Author Alice Echols briefly describes the growth of radical feminism. The several groups that were although different in their fundamental ideologies and goals, contributed to the overall success of the movement. The work continues to the prologue of the book, a chapter devoted to documenting “the civil rights movement and the new left [which] helped to generate the second wave of feminism.”1 Women in civil rights groups such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Students for a Democratic Society soon became involved in women’s rights movements as well while these movements “gave women the opportunity to develop skills and break out of the confining, traditional roles.”2 For many women involved in the civil rights movements, the rhetoric to “describe women’s condition,” although it “incorporated women’s issues into its programs,” excluded women significantly.3 Eventually, an imminent feminist movement grew out of the civil rights movement, with feminist groups arguing for “communal child-care centers, accessible abortion, the dissemination of birth-control information” and other pursuits. Although radical women agreed to separate apart from men, the disagreement over the “nature and purpose” of the separation eventually led to the “Great Divide” or the Politico-Feminist separation.

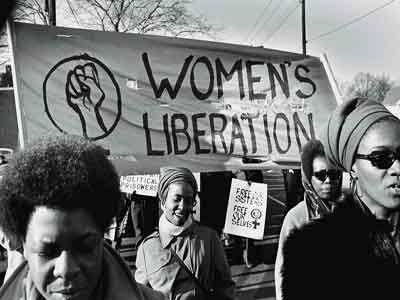

The development of the women’s liberation movement continued until 1969 when differences in viewpoints over the goals of the movement lead to the facture, making “it difficult for radical women to even name their movement.”4 While politicos strongly believed in a separate, all-female group, the feminists argued against “the subordination of women’s liberation to the left” and blamed capitalism and male supremacy.5 Overall, the progression of the civil rights movement eventually led to the growth of the second wave of feminism, which is characterized by the separate feminist groups all contributing to the growth and success of the women’s right movement. Echols continues her work by focusing on the early conferences and protests that embodied the second wave feminist movement during the late 60s and early 70s. In addition, she documents the Movement’s continued antagonism towards the Women’s Liberation movement. Although some groups welcomed black women, most chose not to participate; this was fortunate for the feminist movement as this would have made it “difficult for white women to feel that they could legitimately focus on their own oppression.”6 In addition, conferences and workshops were held to discuss further protests and actions. For example, the Sandy Springs conference decided to “commemorate the 120th anniversary of the first women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls” while a workshop organized by Anne Koedt included women expressing their “deep dissatisfaction with the cultural dichotomization of sex and affection.”7 The progression of the movement was characterized by protests, conferences, and ultimately, achievements.

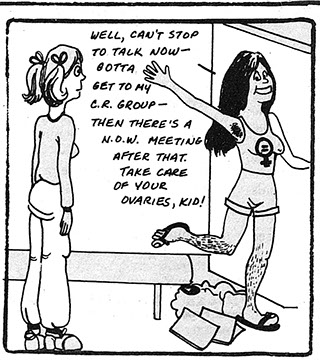

Echols supports her claim that several different radical feminist groups contributed to the overall success of the movement with her documentation of the different strands of feminism during the era. These include the Redstockings, Cell16, Feminists, and the New York Radical Feminists. Throughout this section of the novel, Echols chronicles the major events, fundamental ideologies, viewpoints, and goals of each radical group. The Redstockings protested for abortion rights, held their own hearings of abortion, and were strongly influenced by the left, “appropriating Marxist methodology in an effort to construct a theory of women’s oppression.”8 Cell 16, characterized by their program of celibacy, separatism, and karate, published one of the very earliest radical feminist journals. The Feminists were founded by Ti-Grace Atkinson, who broke away from the National Organization for Women (NOW) because of her more radical ideologies and focused on sex roles as well as the analysis of sexuality. Finally, the New York Radical Feminists were embodied by the women in New York in the hope to build “a mass-based radical feminist movement.” Echols continues describing the intra-movement struggles around issues of “class, elitism, and lesbianism that rocked the movement between 1970 and 1972.9 Eventually these issues contributed to the downfall of radical feminism and the rise of cultural feminism.

Echols ends her novel by describing the supersession of cultural feminism over radical feminism. In 1973, cultural feminism began to challenge the dominance of the latter and in 1975, a series of internecine conflicts between both sects lead to “liberal feminism being the recognized voice of the women’s movement.”10 Echols argues, however, that during the reign of radical feminism, there was some prefiguring of cultural feminism. The author continues discussing the differences between both sects, including ideologies about class and elitism. In addition, she states that opponents of liberation raised questions on lesbianism, another sect that branched out during the Lesbian Feminism Movement in Washington D.C. This had a profound affect and the group dominated the feminism caucus of RPCC. Echols’s work also defines the articulation of cultural feminism, “development of a feminist counterculture, and the radical feminist resistance to cultural feminism.”11 The work ends with an epilogue that analyzes ways in which feminism has developed during the 1970s. This includes the anti-pornography movement as well as the sparked sex debate and stresses the importance the contributions women of color have made to this movement.

Daring to be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967-1975 provides crucial evidence of radical feminist organizations that were influential during the era and establishes credibility through the documentation of historical examples and interviews. Echols emphasizes throughout her work the importance and contribution of the several feminist organizations towards the women’s rights movement. In addition, Echols stresses the difference between radical and cultural feminism and the gradual shift during the 1970s. She highlights the many radical moments and argues that the movement during this era should not credit only “one organization, but many female radical organizations.”12 The author accounts the fundamental ideologies, including the differing views and goals, while emphasizing how each group fought and challenged the ideals of a patriarchal society. One example can be taken from the difference between the goals of the Redstockings, a group fighting for Abortion Laws and the Feminists, who focuses on women’s roles within sexuality.13 Although holding different goals, each group positively impacted the women’s rights movement and the Second wave of feminism.14 Another equally important aspect the author stresses throughout her text is the difference between radical and cultural feminism. The gradual shift from the former to the latter is chronicled throughout her work. Echols utilizes interviews and historical documents to establish and support her thesis.

This novel was written and published during the late 1980s, when the second wave feminism had just ended. The 1980s was a time of great social change and a migration to an industrialized economy. The cold war just came to an end and preceded a great growth of popular culture, including music, film, and sports. President Ronald Reagan promised a “New Morning in America” and reassured that America would move on from the general, political, economic issues that developed during the 1970s. The 1980s also witnessed a greater materialistic society, and therefore the spirit of this decade was associated with extravagance and transformation. According to Echols, “It has been over twenty years since the emergence of women’s liberation movement, and yet … there has been no book-length scholarly study of the movement.”15 Echols wanted to illustrate the difference between cultural and radical feminism, as the formal emerged out of the latter. Her purpose of writing this book is parallel to the great social change and the emerging women figure in society. Sandra O’Conner and Madonna were among the accomplished woman of the era. Much of the success of the women’s movement could be contributed back to the work of the radical feminists, whom Echols wanted to acknowledge and make her readers better aware of their work. The author herself is a cultural critic and currently a professor of English, Gender Studies, and History at the University of Southern California. She received her B.A. in History from Macalester College and M.A. and Ph.D in History from the University of Michigan. Her extensive study about American culture and history makes her a qualified historian about the feminist movement. Echols is the author of several other cultural works, including “Hot Stuff”, “Scars of Sweet Paradise,” and “Shaky Grounds.”

Daring to be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967-1975 elicits several responses out of book critics because of her straightforward description of the history of radical feminism in post-cold war America. Cynthia Harrison, a historian at George Washington University, argues that the issue of radical feminism has been largely overlooked.16 She commends Echols for her vivid reconstruction of the origin, progression, and decline of radical feminism. Harrison notes Echols’s organization of her work around the major splits, such as that between politicos and the so called feminism. To Harrison, Echols portrays the failure of the radical feminists to create a coherent ideology, which eventually leads to their failure and decline. Harrison points out, however, that Echols failed to illustrate the “nexus between radical and liberal feminism.” She completes her critique with an acknowledgment of “the fine and sympathetic” interpretation of the history of feminism that will give “students” a glimpse of women history.17 Alan Morris of Northwestern University also acknowledges the straightforward method the author utilizes to describe the history.18 Morris begins his critique with a summary of the author’s main purpose in addition to the necessity of uncovering the inner disagreements of the radical feminists group. He commends the sophistication in which this modern piece was written as well as the way it “grasps the diversity inherent within the women’s movement while maintaining a critical stance throughout.” Morris states a prominent strength of the book is its analysis of the feminist movement in “context of the social movements of the 1960s.” According to him, Echols effectively explains the significance of the black power movement in the way it shaped the women’s liberation movement. Radical feminism focused on male supremacy as being the major cause of societal inequality. Morris ends his analysis but acknowledging Alice Echols’s work as a major contribution but would only recommend that she add more depth and analysis to the underlying “nuggets” of the feminist inner struggles.

This work contains several impressive qualities that build on the overall reliability and effectiveness of Echols’ work. One major component is her credibility, which she strengthens with interviews with participants from feminist organizations during the era. These personal accounts provide readers with an insider’s opinion on the subject matter. Incorporating these views into her work, Echols provides support for her claim as many of these interviewees were active participants in the movements or even founders of organizations, as in the case of Ellen Willis. Willis, who also wrote the foreword for this book, was one of the founding leaders of the Redstockings, a feminist group fighting for abortion laws.19 Not only does the author refer to secondary sources, but she also enhances her credibility with primary documents such as manuscripts from conventions, as in the Sandy Springs Conference.20 Another attractive component of this piece of work would be the number of examples of different groups the author provides throughout the text to support her claim that several feminist organizations contributed to the overall success of the movement during the 1970s. The book provides introductions to a number of feminist organizations, such as the New York Radical Women in addition to its foundational values and ideologies. However, a place of improvement would be in the overall structure of the book and organization of the content, as this would greatly help the reader to completely understand the material. Overall, Echols accomplishes her purpose of writing this novel: to clearly define the differences between cultural and radical feminism as well as persuade her readers that the latter played a great role in the overall success and effectivity of the movement.

According to author Alice Echols, the 1970’s witnessed a change in the approach to the women’s right movement. Although the feminist movement was a continuation of the sexual and counter revolution of the 60s, cultural feminism supplanted out of the prominent radical feminism of the late 60s to early 70s. In her work, she chronicles the theoretical shortcomings of radical feminism and the changing societal perspectives that lead to its eventual downfall and growth of cultural feminism. For example, she states that the “contradictions and fuzziness of radical feminism also contributed to the emergence of cultural feminism” which included the feminists’ defiance and failure to confront capitalism. Much of their actions were a reaction to the left’s ideologies. However, both groups shared similar goals, embodied with the dismantling of the work economy, new worlds of possibility for education, and the empowerment of women. During the early 70s, radical feminism flourished and had a great impact on the nation, as documented by the Roe v Wade U.S. Supreme Court Case and the Equal Rights Amendment passed in 1972. “The radical feminist wing of the movement” became so “absorbed in its own internal struggle” that it sometimes failed to acknowledge the larger “problem of male supremacy.”21 Echols characterizes the great shift in the feminist movement and second wave feminism in the United States by her documentation of the several splits that lead to the cultural feminism that embodied most of the decade during the 70s.

Alice Echols, in her book Daring to be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967-1975, supports her claim that the success of the women’s movement was the result of works from separate feminist organizations. She does so with the use of credible information, such as documentation and interviews. Echols successfully elicits a deeper understanding and respect for the women during the liberation movement out of her readers with her chronicles of the 1970s.

Footnotes:

- Echols, Alice. 23

- Echols, Alice. 26

- Echols, Alice 27

- Echols, Alice. 53

- Echols, Alice. 53

- Echols, Alice. 107

- Echols, Alice. 111

- Echols, Alice. 143

- Echols, Alice. 21

- Echols, Alice. 243

- Echols, Alice. 22

- Echols, Alice. 295

- Echols, Alice 141

- Echols, Alice. 172

- Echols, Alice. 5

- Harrison, Cynthia. The American Historical Review. 1991. Vol. 96. No.2, 638-640

- Harrison, Cynthia. 640

- Morris, Aldon. American Journal of Sociology. 1990. Vol.96, No. 3, 799-801.

- Echols, Alice. 385.

- Echols, Alice. 369.

- Echols, Alice. 198

4 - 4

<

>