The Native Americans' Quest for Respect

By Shubh Vijay

Bradley Shreve

Bradley Shreve is currently the managing director for the Tribal College Journal. Shreve received his education at the University of New Mexico from 2002 to 2007, where he received his P.H.D in History. Some of his other work includes more in depth information from different decades on the American Indians as well.

The Native Americans have a long history dating even before when America was founded by Christopher Columbus in 1492. The origin of these people dates back almost 13,000 years ago and people to this day are still in question about them. However, the Red Power Movement was a huge turning point for them in the 20th century as, “Historians, journalists, and the activists themselves have told of the men who started the American Indian Movement and their great protests of the 1970s…”.1 The progression of the Natives as a whole shows their determination and courage to bind together and fight for a place in the United States as time goes on, and through leadership, persistence, and intelligence the American Indians were able to hold their ground in society while maintaining their unorthodox culture in American society. In Bradley Shreve’s book, Red Power Rising, he articulates the rise of the Native Americans primarily from the early 1960s all the way till the 1970s, with a central focus on the unity they demonstrated during this time period which was famously called, the Red Power Movement or the American Indian Movement (AIM). There were a significant amount of leaders and supporters that contributed greatly to the development of the American Indian culture as well. From forming unions to passing acts, the American Indians had quite an impact during this decade on the United States as a whole, and Shreve makes sure to take note of every major contribution they made for themselves to ultimately achieve a lasting place in society.

The National Indian Youth Council (NIYC) was established in 1961 by young American Indians who were either in college or had recently graduated from college. The NIYC is a result of youths originating from tribal leaders, which began during the American Indian Chicago Conference in 1961, where several young American Indians became disillusioned with the tribal leaders. After listening to the ideas presented by the conservative faction of the conference, the youth began to express their dissenting opinions. This group, including Clyde Warrior and Mel Thom, temporarily called themselves the Chicago Conference Youth Council. Later in the year, the group met in Gallup, New Mexico. It was there that the National Indian Youth Council was established. Carrying on to the late 1960’s, a group of Native Americans, called United Indians of All Tribes, which, “consisted of mostly college students from San Francisco,” occupied the island to protest federal policies related to American Indians that were being charged at them at the time.2 Some of them were children of Indians who had relocated in the city as part of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) Termination and Relocation’s programs. The BIA hoped to get as many Indians as possible away from the Indian reservations so they could terminate the reservations and take back the land.

With the initial proclamation that was the National Indian Youth Council, this was the main proclamation that spawned the Red Power Movement. At the forefront of the Red Power Movement was the American Indian Movement, which was founded in 1968 in Minneapolis, Minnesota and was the prim advocacy group for the Natives at the time. Its members belonged to and represented mainly urban Indian communities, and its leaders were young and militant. In February 1964, members of the tribes requested the NIYC’s assistance, who had just recently decided to focus on treaty rights. These treaty rights focus primarily on fishing, as it became a huge controversy and something the Indians wanted to take a stand for first. Hank Adams is described as the ‘master mind’ behind what they called “fish-ins”, which he eventually developed into a strategy based on the legal and related economic interests of the fisheries industry. Adams and the NIYC devised a high-profile media ‘fish-in’ with the Hollywood actor Marlon Brando along with a priest. In the following two days, more arrests were made, and the campaign climaxed with a rally of several thousand at the state capitol building in Olympia. The fish-in was modeled after the tactics of the Black civil rights movement, which included sit-ins, rallies, preachers and celebrities. Years later, the Natives won their treaty rights through subsequent legal challenges. After the fish-in protests, NIYC membership grew from about 40 members to over 120 the following year. It was imperative at the time for the NIYC to meet regularly as they did: “The International Youth Conference held in Bismarck. North Dakota, afforded NIYC leaders yet another venue to express their emerging intertribal nationalism. Noble and Hank took primary responsibility for coordinating the event...”.3 But although the group was committed to the campaign, their members were spread across the nation and lacked the resources to continually engage in organizing efforts. After the fish-in, the NIYC attempted to duplicate its civil disobedience campaign in the Pacific Northwest with similar actions on the East Coast and the Southwest. In 1966, Clyde Warrior was elected the NIYC president and by the late 1960s, the NIYC was receiving tens of thousands of dollars in foundation grants and government funding. In 1967, the NIYC invited the Commissioner of Indian Affairs as the keynote speaker for their annual meeting. This action directly coincides with the idea of intertribalism, which has to do with the Indians coming together for a common goal. This idea was universally practiced among the Natives, as this idea promoted the development of their language, common culture, as well as growing their region all at the same time.

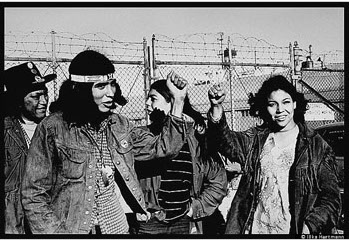

During the height of political disorder in Indian country during the 1960s and ’70s, men such as Dennis Banks, Clyde Warrior, and Vernon Bellecourt were the media-recognized leaders of Red Power, the grass roots movement marked by its activism and a resurgence of Indian cultural identity, pride, and traditionalism. But away from much of the media attention stood such women as Madonna Thunder Hawk, Lorelei DeCora, Janet McCloud, Pat Bellanger, Lakota Harden, and LaNada Means War Jack. These were just a few of the Indian women in the depths of the Red Power Movement. Shreve credits the NIYC for the much greater role of women, than in other similar groups: “The NIYC also followed their elder’s example in that both men and women shaped and led the organization. Like their forebears in the American Indian Federation, women played a pivotal role in the council—the organization’s initial first and second vice presidents were women.”4 The movement gained international prominence in 1968 with the founding of the American Indian Movement, in Minneapolis. This Red Power movement also had significant similarities with other movements especially the Black Power movement that gave inspiration for the Natives in their future endeavors to accomplish their goals. The Black Power movement and the Red Power movement were both equally important to each other and showed that both races had to fight for certain liberties and rights. A number of protest camps by the NIYC were also established during the early 1970s, as the purpose was to continue the fight for equal treatment as the general society. During the same years, government buildings, such as the main headquarters of the BIA in Washington, D.C., also became the sites of protests. Many of these protests and occupations included celebrations of Indian culture and ethnic renewal, while others included efforts to provide educational or social services to urban Indians. As the 1970s proceeded, American Indian protest occupations lasted longer. An example was the November of 1972 weeklong occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington, DC. This unplanned stint occurred at the end of the Trail of Broken Treaties, a protest event involving caravans that traveled across the United States to convene in Washington at a large camp in order to dramatize and present Indian concerns at the national BIA offices. The American Indian Movement’s first attempt at a national protest action came on Thanksgiving Day, 1970, to challenge a celebration of colonial expansion into what then was mistakenly considered to be the New World. During this action, AIM leaders acknowledged the occupation of Alcatraz Island as the symbol of a newly awakened desire among Indians for unity and authority in a white world.

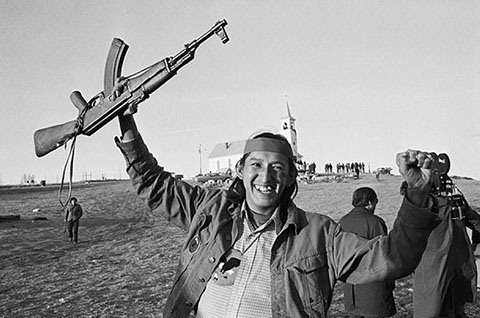

From this beginning, AIM mounted actions both off the reservations and on them. The involvement of urban Indian individuals and groups, such as AIM, in protest actions situated on reservations revealed tensions inside Indian communities. They also took place among the political divisions on the reservations themselves. All of these tensions became magnified as the activism of the 1970s progressed. The tone of protest became less celebratory and other-directed and more harsh and inward. Not a single event during the Red Power Movement age clearly illustrated the combination of Indian grievances and community tensions than the events on the Pine Ridge Reservation in the spring of 1973, a ten-week-long battle that came to be known as Wounded Knee II. The conflict at Wounded Knee, a small town on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, involved a dispute within Pine Ridge’s Oglala Lakota (Sioux) tribe over the controversial tribal chairman, Richard Wilson. Wilson was viewed as a corrupt puppet of the BIA by some segments of the tribe, including those associated with AIM. An effort to impeach Wilson resulted in a, “division of the tribes into opposing camps,”5that eventually armed themselves and entered into a two and one-half month long siege that involved tribal police, government, officials from the American Power Movement, reservation residents, federal law enforcement officials, and legal organizations.5

Shreve piles the book with several important facts with outstanding analysis, however what makes this book great is the point of view from his own perspective he applies to the book in clever spots. One distinct area of evidence for which he implies his purpose is on the very first page, where he states: “This book seeks to illustrate how these episodes, and their main actors, followed in the footsteps of an earlier generation”.6 This is a great analogy to how a movie in the current generation develops much like a society back in previous decades. Shreve refers to an earlier generation in order to show that the American Indians did not want their culture to die after them being discovered in the Americas in 1492 by Christopher Columbus. Shreve’s attempt to display his knowledge and the journey the Natives have endured ultimately became a success.

Bradley Shreve has the creditability to write such a detailed book in this field because of his major in history with a focus on American Indians. He has produced several articles as he works for the Tribal College Journal and has studied at the University of New Mexico for 6 years. His extreme knowledge about the history of the American Indians tremendously helped in making Red Power Rising a standout classic. Published in 2011, Red Power Rising was a complete and full circle summation of the Indians and how they came to be in today’s society. 2011 was a good year for Shreve to publish this because he was able to remind readers of this group that gets often overlooked in their culture and origin by society in the 21st century.

This book was a great documentation of how the Native Americans came to be who they are today and the prominent religion and culture they are in today’s world. One critic from the North Coast Journal thought that, “Shreve’s chapters are skillfully crafted to tell an absorbing story, as individuals grapple with issues reflecting the unique history and circumstances of American Indians from the Teddy Roosevelt and FDR eras through the wild 1960s and 1970s.”7 This book is informative and judicious (with good notes and sources) but enlivened by detail and reminiscence. Another article that had some criticism, but came off positive, was posted on Warrior Publications, which has a focus on American Indians and its history as well, “Although Shreve overstates the importance of the NIYC, the book is nevertheless a good documentation of early Native youth organizing.”8 It also sheds light on the positive contributions the NIYC made to the indigenous struggles in North America. There are also many parallels to Native grassroots organizing of today that one can learn from. And, despite Shreve’s effort to revise the history of Native grassroots struggles, it also reaffirms the fact that urban centers have served an important role in unifying these struggles through intertribal organizing.

Bradley Shreve finds the roots of American Indian activism in the nascent inter-tribal organizing of the early 20th century and the various attempts at fashioning independent organizations of dedicated native youth over the following decades. In the process, Shreve demonstrates how the militant actions of the 1960s and 70s are reciprocated by a generation from the past as well. He writes, “Indeed, movements for social change do not emerge in a vacuum. They are built upon precedent, they incorporate and borrow ideas from the past, and they may find inspiration from contemporaries.”9 This is a story of the past informing the present, of movements building on tradition, and the dramatic arrival of an era of self-determination.

Shreve, through his book, gives the Natives a place in history, particularly in the 1960s through the 1970s, by describing the chronological development of the Indians and what they meant in America. The events that transpired as part of the Red Power movement was most definitely a continuation of the 1960s and were able to be handled more efficiently in the 70s because of the previous trial and error faced in the last decade by the National Indian Youth Council. This movement was extremely vital towards American history in the 1970s because it put a figurative “stamp” and put the Natives on the map to continue their expansion for their culture throughout the states.

Looking at this documentation as a whole and what it represents towards the 1970s and the importance it holds, it demonstrates a culture that independently went through several trials and tribulations to achieve a sense of equality. The Native Americans, through their struggles and their years’ worth of efforts with their acts, bills, movements, and battles, found a way to cement themselves as a united group on this earth. They made it their mission to not let, not only their culture but also their traditions; decay over time, as it is a history over countless centuries. Overall, this book was a pleasure to read and serves as an excellent example for summarizing the Native People and their accomplishments during this span.

Footnotes:

1. Shreve, Bradley. Red Power Rising. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011. 3.

2. Shreve, Bradley. 45.

3. Shreve, Bradley. 144.

4. Shreve, Bradley. 4-5.

5. Shreve, Bradley. 130.

6. Shreve, Bradley. 3.

7. "Red Power Rising: The National Indian Youth Council and the Origins of Native

Activism." The North Coast Journal Weekly.

8. “Red Power Rising: The National Indian Youth Council and the Origins of Native

Activism." Warrior Publications. 31 May 2011.

9. Shreve, Bradley. 16-17

4 - 4

<

>