Apple Evolution

By Victoria Guan

Michael Moritz

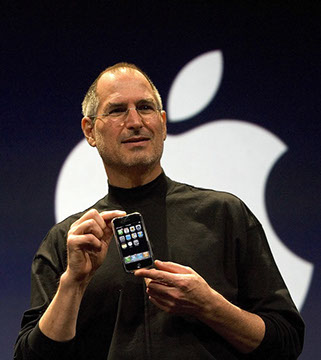

Born in September 12, 1954, Michael Moritz is a Welsh venture capitalist in Silicon Valley and a philanthropist. He earned a Bachelor degree of Arts and Science in Oxford University and later a Master degree of Business in University of Pennsylvania Wharton School. He began as a journalist until he was recruited by Steve Jobs to become Apple’s historian.

The Apple Corporation has always been the star in the 1970s and still is today. Michael Moritz, author of Return to the Little Kingdom: Steve Jobs, the Creation of Apple, and How it Changed the World, concentrates on years before Apple’s major success and the effect of the unique personalities of its early founders on the company. Some of its success is contributed by the well-known Steven Jobs and the brilliant co-founder Stephen Wozniak. However, little do people realize that prior to the 70s, Apple began in a living room; it was slowly nourished by the early surrounding companies’ competition in Silicon Valley. Although Apple was one of the many companies originated in Silicon Valley, it was Silicon Valley’s “most precocious child.”1 Within eight years, it exponentially rocketed from a garage to a company worth $1 billion and a value of more than $2.5 billion for its shares. Moritz’s work is a classic, narrating the tedious yet booming success of Apple.

The beginning of the book skips back to the fifties, where Santa Clara Valley was predominantly rural. Although the cities were similar in the “manners and style of the thirties,” each was separated by differences such as its climate and its stage in industrialization.2 The introduction of the suburban life led to the increase of Santa Clara Valley’s population, especially in the city of Sunnyvale. Families who moved to Sunnyvale flocked to prospect of jobs at Lockheed and scavenged the reputations of surrounding, new schools. Moritz then introduces Jerry Wozniak, engineer and father of Stephen Wozniak, and Paul and Clara Jobs, who adopt their first child, Steven Jobs. Stephen Wozniak as a young child began to take interest in the popular field of electronics. He built many inventions, including a 100-watt ham radio, designs for electric circuits, and a One-Bit Adder-Subtracter, which was an early form of a calculator that could add or subtract numbers; the calculator earned him first place in the Cupertino School District Science Fair and landed him third in the Bay Area Science Fair. In his adolescent years, Wozniak completed—with the help of Bill Fernandez—his first computer named the Cream Soda Computer. Unlike Wozniak’s prosperous childhood, Steven Jobs lived in a poor condition, where his father had built most of the house appliances. He constantly changed schools because of their low-income situation.

The original cofounders of the Apple Company, Wozniak, Bill Fernandez, and Jobs, eventually came to know each other. As Moritz humorously describes the peculiarities of the three, they were loners and were fixated on electronics. Jobs, unlike Wozniak, was not a teacher’s pet and had done drugs in his teenage years because of his connections with university students. His first girlfriend was Nancy Rogers, and because of her, he took partial interest in literature, such as poetry, guitar, and school plays. Wozniak, although successful in the beginning, devoted his time to the blue box, an early form of a telephone, and his computers, leading to the “fallen foul of a college dean” and received “letters scolding him for his poor academic performance.”3 Jobs on the other hand persuaded his parents to send him to Reed College despite high tuition bills. When he finally arrived, it was a campus of “loners and freaks” and had a high philosophical influence in literature.4 Eventually, Jobs returned back to electronics in Sunnyvale and looked for a job, leading to his position as a technician in Atari. Despite his lack of formal electronic training, jobs merged the gap between a technician and an engineer, understanding each chips’ subtleties.

While Wozniak completed his first custom computer called the Cream Soda Computer, Jobs remained capricious, switching back and forth between computer companies. He knew he wanted to be an electronics technician and not an engineer like his father. In result, Jobs attended physics in Stanford University for gifted freshman. Jobs and Wozniak eventually founded the name of their company—Apple—only because “the simplicity of Apple always seemed more appealing than Executek and Matrix Electronics.”5 With the soon partnership of Ronald Wayne, the trio proposed the partnership agreement of the Apple Company and turned attention to assembling and testing the computers. The actions of the Homestead Club, which was participated by the three, merged in with Apple activities because of Jobs and Wozniak, and they took into consideration the visual appeal of their product. Jobs and Wozniak were later introduced to McKenna, who started his own company in the 70’s because of the takeover of the National Semiconductor and was responsible for the image of Byte Shops and advertisements for Intel’s single-board computers.

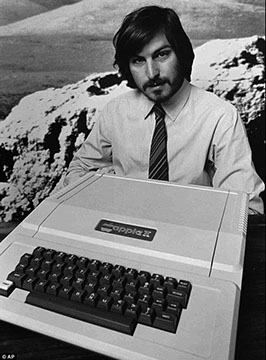

The release of Apple II, to the joy of Jobs, was ranked third behind Zaltair and Altair 8800-b. Primarily, the men in the Apple Company concentrated solely on Apple’s bodily functions from scratch. However, the introduction of Mike Markkula into Apple gave way to Apple’s business plan for aesthetics rather than function. New employees raced into the Apple Company, leading to a “natural division between the older engineers and the younger ones, who were content of prototype.” 6 Because of its rush to complete items, Apple often received criticisms from others and turned to familiar faces for help. Apple eventually reached its peak of success and eventually led to “zillionaires” of its founders. Moritz here however turns to the personal problems of Wozniak, who sold shares to only colleagues and Jobs, who had a daughter with his ex-girlfriend. But despite this, Apple continued to climb as new clubs formed because of it: Apple Tarts, Apple-siders, Apple Peelers, etc. Even in the course of a quarter of a century, Apple outran most computer corporations. Although Jobs was fired due to incompetence from Apple, his NeXT Company eventually merged in with Apple’s and caused his rehiring. Moritz concludes the book with Apple as the symbol of ingenuity and enterprise.

The main question that Michael Moritz addresses through the book is how Apple maintained its success and how it transformed from a garage into a corporation worth billions of dollars. From each chapter, he switches between the substantial growths of electronics from the fifties to the eighties and the effects of the unique personalities of Apple’s early founders in the Apple Company. Because of the beginnings of the electronic age, Apple was scooped up in the “hay fever.” The brilliance of Stephen Wozniak in the computer field and the calculating mind of Jobs in profits led to the development of the early company into the major success it is today. However, it was not solely the influence of its cofounders was its success. It was the combination of the Apple crew’s effort and the sense of security the 1970s gave to the founders of Apple: “I was getting a chance to do something they way I thought they should be done. I felt I had nothing to lose ... because I could always go back to the company.”7

Michael Moritz is a Welsh venture capitalist in Silicon Valley and a philanthropist. He was originally a journalist, who was contracted by Steve Jobs in the early 80’s to record the history of Apple. However, Time magazine molded Moritz’s interpretation into a grotesque portrayal of Steve Jobs and the other cofounders of Apple. Consequentially, Steve Jobs was incensed and cut off all ties with Moritz, threatening to fire anyone who spoke to him. Even in the prologue of the book, Moritz recalls the situation of Time’s portrayal of Steve Jobs, causing his dismissal as the historian of Apple: “the experience made me decide that I would never again work anywhere I could not exert a large amount of control…”8 The rash situation Jobs made may have caused Moritz’s bias on the history of Apple despite Moritz’s passive voice on the description of Steve Jobs in his book: “He, understandably, banished me from Apple…”9 Even though Moritz was fired, he has been significantly influenced by the company since his early career was based on Apple. His 2009 book is in fact an updated version of his previous book published in 1984, Return to Little Kingdom: the Private Story of the Apple Computer. Rather than his biography affecting the book, his research on the history of Apple may have affected his life, especially as a philanthropist.

Elin B. Christianson summarizes Return to the Little Kingdom: Steve Jobs, Creation of Apple, and How it Changed the World in a brief sentence: “This is a microchip-by-microchip account of Apple Computer. Inc., from its hobbyist origin to billion-dollar-plus corporation—a journey of less than eight years” Christianson focuses primarily on what Moritz explains as Apple’s basic cofounders: Wozniak and Jobs.10 With individual personalities clashed harshly from hobbies into a company, Apple struggled into what it is today. Surprisingly, Christianson possesses no critical harshness towards Moritz’s work and in fact recommends the book to businesses and computer collections. This may be because Christianson is a library consultant and perhaps not a historian. In contrast to Christianson, William Stockton criticizes how Moritz had not successfully completed his task in only describing how a modern high-tech company “springs into being and grows topsy-turvy.”11 In addition, he claims that the vignettes, provided by Michael Moritz in the behind-the-scenes events at Apple computer, are useless and that the reader could easily skip them. Sometimes the vignettes do not even correlate to the continuation of the Apple history. Nevertheless, he praises Moritz for handsomely recounting how Jobs and Stephen Wozniak stumbled into the right place at the right time to carve a permanent niche in the history of technology.

Return to the Little Kingdom: Steve Jobs, Creation of Apple, and How it Changed the World is controversial in the field of its context. Based on the title, a reader would expect a biography of Steve Jobs, the origin of Apple, its success, and finally the impact it held worldwide. Instead, it is a clump of technological history that is not only based on Apple—there is the Hewlett-Packard, the early Atari, Sony in its final statements hidden in the epilogue, and a mass of undefined, technological terms blank to a novice; this unfortunately leads to a confusing amount of history blended into the book. Although it is refreshing to gain information of the technologies each decade, it appears as a blend of companies rather than the focus of its title. More importantly, Steve Jobs was not the center of the universe in the creation of Apple in contradiction to Moritz’s given title. He did appear as the major figure in the beginning of the work, but as the book later demonstrated Apple’s cofounder Stephen Wozniak was a more significant figure in Apple than Steve Jobs; “early investors, such as Don Valentine, were major contributors” to Apple’s stepping stones.12 Finally, as William Stockton had described, the vignettes seemed irrelevant to the historical context of the book; they had concentrated only on the marketing ads for Apple’s sells and diverged from each chapter’s topic. Nevertheless, the book satisfied the hunger of knowledge for the 1950-1970s and is brilliant in retracing its steps back to Apple’s origins.

What position does Moritz take of an era known for being a time of severe crisis in the United States? Based on his work, the 1970s was a gilded age of technology and the focus of success for companies. The huge consumer profits from personal computers and the gradual change from large, custom computers into smaller, condensed minicomputers explained the process of shortcuts wanted, where smaller and more effective was better. The creation of the Apple III computer after the Apple II computer was a complete failure because of the lack of worry for programming and function; it was more on aesthetic appeal and the continuation of Apple’s logo brought into public. In the past when Wozniak designed his first computer, the Cream Soda Computer, he “spent hours working out where the chips should be placed before plugging the sockets, the cradles for the semiconductors, into the board…the fastidious approach paid off when it came to troubleshooting and made it...”13 Yet in the later years of the Apple corporation, the computer “that appeared at the West Coast Computer Faire was not one person’s machine anymore. It was the product of collaboration and blended contributions in digital logic design, analog engineering, and aesthetic appeal.”14 Inadvertently, the one man-made computer for functions was revamped into one considering partial function and design. Unlike the previous eras of small businesses during the 1950s and the 1960s, the 1970s was a period of successful, competitive corporations with dying small businesses. Again, it was an age of monopoly based on the concepts of the early Industrial Age—the fittest survive and the weakest become extinct.

Overall the Apple Industry was a miraculous success, originating from a hobby into a ‘zillionaire’ company today. With the contribution of investors, engineers, and electronics technician, Apple was nourished in its success. All it took was the span of eight years for an average electronics living room to suddenly transform into something unrecognizable today, sharing billions of shares and giving zillionaire titles to its cofounders. However, for Apple now, “what comes next? Can it continue to produce encore performances?”15 For now the present can say yes, but will the future see Apple’s continued success or its final demise?

Footnotes:

- Moritz, Michael. Return to the Little Kingdom: Steve Jobs, the Creation of Apple, and How it Changed the World. The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc. 2009. 19.

- Moritz, Michael. 30.

- Moritz, Michael. 132.

- Moritz, Michael. 144.

- Moritz, Michael. 301.

- Moritz, Michael. 159.

- Moritz, Michael. 12.

- Moritz, Michael. 13.

- Morrow. Sept. 1984. C.400p. bibliog. index.

- Collins, Eliza G. C. “Books & Business; Business in Short “Dearest Amanda...”: An Executive’s Advice to Her Daughter.” The New York Times 21 Oct. 1984, sec. A: A.50. Print.

- Moritz, Michael. 14.

- Moritz, Michael. 134.

- Moritz, Michael. 199.

- Moritz, Michael. 341.

- Moritz, Michael. 352.

4 - 4

<

>