Author Bio: Colin Harrison is a Lecturer in American Studies at Liverpool John Moores University. His work is published through the Edinburgh University Press.

| Home |

Sign of the Times |

Back |

Author Bio: Colin Harrison is a Lecturer in American Studies at Liverpool John Moores University. His work is published through the Edinburgh University Press.

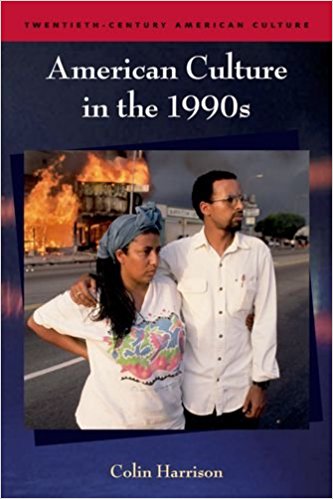

I did not inhale’ is only half a denial”—President Bill Clinton’s vague statement about his supposed marijuana usage summarized the attitude of the 1990s. The acknowledgement of illicit activities contradicted with the blatant denial of said activities clarified the nineties attitude of a ‘rebel without a cause’. Clothing the period in approval yet disavowal, 1990s American culture assumed a racially forward, feminist, progressive message whilst bolstering traditional American ideals. Ideals contrasted in Colin Harrison’s work, American Culture in the 1990s, in turn, painting the New Economy, globalism, and the Information Ages as pictures of protest. Harrison alluded to “The Sixties in the Nineties” characterizing how, like the upheaval of the sixties, which eventually subsided, the progressive wax of the nineties melted in the heat of extrinsic terror, stifling the effects of true change. The American Dream that carried hope during the Cold War seemed veiled by the inequality of capitalism. The American Dream had died. Fragile, the arts and pop culture of the 1990s stood strong in the face of the Gulf War, yet, ultimately crumbling in the ruins of 9/11.

The 1990s created a culture at risk when reading loss rates among the American population meant that leisure reading would “virtually disappear in half a century.” Harrison captured the paranoia of a post-literate culture in the rise of the book club, popularized by The Oprah Winfrey Show in 1996. The danger of book clubs stemmed with the mass production of literature in which an Oprah seal “guarantee[d] millions of sales.” Commonplace literature created fear of collective mindlessness over good taste. Nonetheless, literature’s commercialization forced celebrity cult status on authors. Collectivising the reading experience also made room for “discourse… on social issues.” When Toni Morrison’s book, Paradise, appeared on Oprah it ignited conversation on African American identity. Likewise, Asian authors Lawson Fusao Inada and Li-Young Lee redefined Asian-American identity, demonstrative of how “Identity is no longer...a definition of what is proper to a community,” Lee and Inada depicted coming of age in urban Chinatowns, in which youths assumed full identities of both Chinese and American, rather than the the isolated Chinese-American stuck between two worlds. Asian American authors attacked the stereotypes of hyphenated Americans, reinforcing the idea of a ‘Tossed-Salad’ America. An influx of immigration raised a generation planted in foreign soil, but dressed in American culture. Despite the great racial strides literature made in the nineties, Harrison sheds light on the discontent with the American Dream in the books American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis and I Married a Communist by Philip Roth. The American Dream nourished the collective spirit against the daunting Cold War Years during the second half of the twentieth century—America offered opportunities for success: a strong nuclear family unit, a supportive community, civil liberties, and chances for capitalistic gain. Ellis blatantly shunned empty materialism--tied to capitalism—promoted by 1980s Reaganism. Ellis’ psycho, Patrick Bateman fills the cravings materialism fails to fill by practicing serial killing. In the meantime, Roth told the truth of the tearing of 1960s intellectual, Jewish neighborhoods due to McCarthyism-era panic. Critical literature of the 1990s confronted national histories on a global scale, uncovering the atrocities accumulated by American society. Radio, too, fell under commercialization. T

he Telecommunications Act of 1996 initiated the conglomeration of radio stations, birthing the genre of alternative music. Alternative music capitalized garage music and “denoted a real loss of independence to major labels and corporations.” The grunge culture fed off “numerous attempts to repudiate the authority” exemplified by the alternative rock band, Nirvana. Nirvana’s “Teen Spirit”, named after cheap deodorant and made with hastily constructed lyrics, meant the death of traditional rock ‘n’ roll. Where traditional rock ‘n’ roll repudiated authority with an invigorate, pulsing purpose, alternative music like Nirvana worked to promote aimlessness while seething in angst. Nirvana grew as middle-class youth resentment escalated; they felt trapped by strictures of suburban life enforced by the American Dream. In 1994, the suicide of Nirvana’s lead singer, Kurt Cobain, assured the survival of traditional rock n’ roll while enforcing alternative’s aimless, self-serving values: “It’s better to burn out, than fade away.” Alternative music’s feminist statements manifested in the sub-genre of Riot Grrrl bands. Riot Grrrls abandoned feminine convention, dressed with the “harlot/baby-doll look” painted with the words “BITCH, SLUT, and RAPE” to make it difficult to objectify their sensual performances. Riot Grrrl bands raised public awareness to domestic abuse and societal inequality, yet created the stigma of “angry feminists” that continues to taint the gender equality movement. Enflamed performances by Riot Grrrls bands such as Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, and Heavens to Betsy paved way to tame pop-music “girl power acts” such as Britney Spears. Time magazine dubbed the United States a ‘hip hop nation’. Rap music rejected the notion of making logical sense to accept “messages of hope or displays of nihilistic bravado”—Ice-T, Ice Cube and associates Niggaz with Attitude (NWA) crafted ‘gangsta rap’ rejecting political organization in favor of “ghetto America.” Rap’s anger against authority assaulted the American Dream with it’s alternative escapism. East Coast Rap, created for dance, duked against Hollywood-influenced West Coast Rap, with both sub-genre’s respective icons, rivals Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls murdered in 1996. Tupac Shakur became an immortalized martyr of black disenfranchisement post-mortem. As the son of a Black Panther, “activist and visionary to outcast and player,” Tupac’s rap gives tribute to black nationalism and ‘thug-life.’ Tupac’s shooting on the Las Vegas strip, supposedly by his record label, brewed further suspicion of capitalist interests--materialism murdering anyone who protests. Rap culture’s introduction of dance music manifested in the DJ creation of ‘house and techno’. Dance Music focused on “perception instead of representation...ego-less subjectivity” unifying strangers on the dance floor with meaningless, nevertheless enjoyable synthesizing.The Nineties’ Broad spectrum of music was free for download. In 1991, Napster, a peer-to-peer music ‘sharing’ site questioned artists’ rights by prematurely releasing songs for personal piracy. Napster’s end in 1999 closed the nineties music era along with killing the dreams of Kurt Cobain’s rebellious youth and Tupac’s Social Justice.

Television inflated the United States’ involvement in the Gulf War in 1991 against Saddam Hussein’s occupance in Kuwait as a fight for good against tyranny. Iraq broke the “Vietnam Syndrome” of dejected US military involvement.The televised War portrayed a conservative bias, with visa denial to liberal-leaning media news, such as: Harper’s, Mother Jones, and The Nation,whilst naming missions romanticised titles: ‘Desert Storm’ and ‘Desert Shield.’Likewise, the rise of television raised questions in in regards to the 1991 beating of Rodney King and the 1994 O.J. Simpson trial. Motorist Rodney King’s clear mistreatment at the brutality of the LAPD, recorded on home video, was convoluted by the court to testify against King. These atrocities led to a series of anti-police sentiment, including Ice-T’s rap “Cop Killer”and a six day Los Angeles Riot in April 1992.The O.J. Simpson trial received 42% of American viewings, overshadowing the Bosnian War and the Oklahoma City Bombing. The sex, drugs, and dethroning of the interracial posterboy was further elaborated by a slow-speed, made-for-tv car chase through Los Angeles. “Event Movies” such as 1991’s Aladdin, and Terminator II, and 1993’s Jurassic Park generated a trend of film-franchise profits, with promotional merchandising and interactive amusements. Aladdin toys, Terminator “I’ll be back” royalties, a Jurassic Park themed amusement ride pumped money into the ever growing media conglomerate. Independent film also saw a rise when the Sundance Film Festival of 1984 grew to the most sought after low budget film festival, praising Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction as the most profitable film. Pulp Fiction satirized “event movie” tropes of Hollywood, drawing in a cult following. Following reality shows like MTV’s The Real World grew as a national pastime. The Real World promoted liberal ideals of safe sex and acceptance, and animations also expanded beyond child interests when The Simpson’s scorned the American nuclear family.

Modern art meant to fabricate metaphors for a complicated reality.Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled candy-spill artwork stood in place of the rainbow plethora of lives lost in the 1980s AIDS crisis, while Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum rearranged confederate silverware to cage slave manacles, showing how old tensions die hard. From the obscene to the nonsensical, artists of the 1990s utilized art as free speech. Conservative politics butt heads with art when Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ, an anti-establishment depiction of a soiled crucifix, made way into public exhibitions. The war on “taxpayer funded obscenity” failed to suppress the further contagion of free-speech against censorship.In 1994, the World Wide Web “realized its potential for mass networked communication.” Activism, goods pricing, and news—the Lewinsky affair “Lived and died on the web.” Online actions grew to contrast VR- virtual reality, and RL-real life—games with avatars (fictional characters operated by users) had potential for moral behavior, blurring the lines between reality and experimentation. The availability of VR games possessed probable potential to press violent imprints volatile minds. Amazon’s sale of books made money off “crowdsourcing” in which values are realized by amounts purchased. eBay’s popularity raised concerns of debt and labor—shopping rationally when online credit buying led to shopping sprees, and jobs sent overseas, cheaply meeting supply and demand. Fear fermented when free-trade online offered no protections for the people. In 1990, artificial genetic intervention through The Visible Human Project spent $3 billion, and projected the answers to the mysteries of human origins by mapping the human genome along with turning ‘on’ and ‘off’ cell growth.Genetic mapping assured Americans that they had power over nature into the new millennium.

Colin Harrison stated that, “ Lodged between the fall of Communism and the outbreak of the War on Terror, the 1990s was witness to America’s expanding influence across the world, but also a period of anxiety and social conflict.” American culture during the 1990s reflected a warping of the American Dream, yet lacked the direction to make the dream a reality. America lay crippled by the “Vietnam Syndrome”and scorned the American Dream that was blamed for promoting superficial success in a world of suffering—both symptoms of skepticism from the end of the Cold War. In the “years in-between...history might move in a number of very different directions.” At the same time, the majority of Americans experienced the hope in the Gulf Wars, entertainment in mass-mediums, free expression in the arts, access to the world wide web. Harrison’s reasons for writing American Culture in the 1990s may be summed up to his idea of “the Sixties in the Nineties”. While never explicitly depicting American Culture in the 1960s, Harrison clarifies the trend of a cyclical history—in which history repeats itself. Much like the youth of the sixties, and of the twenties, the youth of the nineties indulged in a culture—attitude and expressionism—shedding the sins of past wars, yet misunderstood by previous generations. Modern art, alternative rock, grrrl power bands, book clubs all cemented an indelible plaque of progressivism. Despite the progressive strides, Harrison ominously reveals the murder of this brand of progressive ideology with the world-wide-web, online trade, monopolies, and commercialization. The era of contradictions lies in popular culture’s ideals warring against the industries that fuel them. “Rebel Teens” used their middle class parents’ money for Nirvana concerts, the trial O.J. Simpson: the crucifixion of the racial-integration spokesperson. Actions speak louder than words; Nineties culture is defined not by direct movements or actions, but the confusion from it’s place in time. Colin Harrison’s exhibition of a lost culture justifies the dazed haze of angst and social rebellion in the Nineties as a lost adolescence shaped both by the morally coercive, materialism of the 1980s preceding it, only to fall into the War on Terror that forced the Nineties to shed its sense of disorder and unify in the face of danger.

Colin Harrison is a lecturer in the American Studies Department at the Liverpool John Moores University. As a British citizen, he recalls historical happenings with objectivity. Harrison’s objectivity allows him to maintain a neutral tone throughout the work. When commentating on the social consequences of historical happenings, Harrison’s British nationality leads him to lean towards progressive historiography. When the United States assumed the role of world protector in the Cold War, Britain undertook decolonization in order to cooperate with the welfare state espoused by the Labour Party. In this sense, Harrison sympathizes with reform driven artists, focusing on their strides towards rights. Written in 2010, in the midst of Barack Obama’s Democratic presidency, and a turn to Gordon Brown’s term a a Labor Party prime minister; a progressive turn in politics emerging from a prior conservative term. Harrison prefers a progressive viewpoint in what he believes is a cyclical movement of history in which similar trends always come and go.

Book critic, Neil Jumonville’s article, “Learn this Forward but Understand it Backward”assesses Harrison’s work as something “[un]imaginable a few decades ago” it lacks electoral politics. As an art commentator, Jumonville clarifies that “many members of the art committee are unhappy at [American Culture in the 1990s’] decreed criticism of society”.Much like the 1990s attitude towards alternative music, Jumonville cautions that Harrison leaned too closely to popular conventions--”interests of the market”, rather than examining quality art. Conversely, Christopher Vardy’s Review in the 49th parallel, the University of Manchester’s newspaper, demonstrates his enthusiasm for Harrison’s work in relations to his personal major in American Studies. Vandy remarks positively on Harrison’s work in congruence. Vandy views that Harrison poorly manipulates the idea of “heterogeneous” culture, when in reality, Harrison’s work presents a more “complex, critically useful vision: examining the complexities and disjunctions”of cultural preoccupation. Vandy focuses on Harrison’s knowledge of historical movement trumping his grasp of art history.

Colin Harrison’s work offers a progressive leaning, but overall objective take on ‘90s pop culture. Though the text offered informative analyses on the intellectual effects of the arts and culture, it accomplished little in appreciating the culture itself. For instance, in Chapter 2: “Music and Radio”, Harrison mentions various artists, yet clumps them together to simplify their work.In simplifying complex artists, he fails to appreciate the beauty, values, or emotional significance that the art bears for the minority groups it represent. Harrison’s generalizations rely on broad themes, therefore, vague analysis becomes dry for the reader. Colin Harrison’s work offers an insightful perspective, yet falls flat in human interest.

[1] Harrison, Colin. American Culture of the 1990s. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 12

[2] Harrison, Colin. 11

[3] Harrison, Colin. 35

[4] Harrison, Colin. 36

[5] Harrison, Colin. 38

[6] Harrison, Colin. 48

[7] Harrison, Colin. 72

[8] Harrison, Colin. 79

[9] Harrison, Colin. 82

[10] Harrison,Colin. 87

[11] Harrison, Colin. 91

[12] Harrison, Colin. 99-100.

[13] Harrison, Colin. 105.

[14] Harrison, Colin. 127-128

[15] Harrison, Colin. 137-138.

[16] Harrison, Colin.134

[17] Harrison, Colin.172.

[18] Harrison, Colin. 173.

[19] Harrison, Colin. 183.

[20] Harrison, Colin. 194-195.

[21] Harrison, Colin. (Back Cover).

[22] Harrison, Colin. 208.

[23] Harrison. Colin. (Back Cover)

[24] Jumonville, Neil. “Review-Essay:Learn This Forward but Understand it Backwards”. Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol.73. Num.1. 2012. 148

[25] Vandy, Christopher. “49th Parallel, Vol 29”. University of Manchester. 2012.

[26] Harrison.Colin. 65-96.

[27] Harrison, Colin. 199-208.

[28] Harrison. Colin. 102-109.